Introduction

The 21st century is being shaped by a defining contest between two superpowers: the United States and China. While headlines often reduce this rivalry to trade wars or military maneuvers, the deeper battle is over the very models of governance, values and innovation that will guide humanity’s future.

We aim to explore two foundational questions: Is America prepared to meet the challenges of the 21st century, and if not, does it possess the capacity to adapt in order to do so?

The United States, born out of a constitutional commitment to laws and legal principles, has developed a deeply legalistic culture that shapes not only its governance but also its approach to business and innovation. American institutions emphasize regulation, litigation, and contractual frameworks, creating an environment where precedent, process, and risk aversion often take precedence over speed and experimentation. This orientation is vividly illustrated by the composition of its professional workforce: the U.S. has nearly as many lawyers as engineers with about 1.3 million lawyers compared to 1.6 million engineers, a balance that underscores the centrality of legal reasoning to American society.

China, by contrast, has fostered an engineering-led culture that places technical expertise at the center of national development. Each year, it graduates roughly 1.4 million new engineers, a number nearly equal to the entire stock of engineers in the United States. In total, China now has an estimated 18 million active engineers, compared to only about 650,000 lawyers. This inversion of professional priorities reveals a society that prizes problem-solving, system-building, and large-scale implementation over the interpretation of legal precedent.

Since World War II, the United States, having secured immense wealth and global dominance, has increasingly defaulted to courts, contracts, and risk management as the means to protect its gains and navigate its growth. By contrast, China has leaned on its vast pool of engineering talent to design, build, and expand the foundations of its growing prosperity. The outcome is a stark cultural and structural divergence: America channels much of its intellectual capital into managing business opportunities through legal frameworks, while China directs its human capital into engineering capacity aimed at transforming physical, industrial, and technological systems. This divergence not only defines their domestic priorities but also shapes how each nation approaches global competition in the 21st century.

Impact on Innovation

This divergence in professional emphasis has profound consequences for how each country innovates. The United States’ legalistic culture fosters an environment where creativity thrives in consumer-facing sectors like software, entertainment, finance, and biotech startups, because intellectual property protection, venture capital contracts, and regulatory frameworks give entrepreneurs both incentives and guardrails. America’s strength has been in generating breakthrough ideas and rapidly commercializing them in global consumer markets, whether in the form of Silicon Valley apps, blockbuster drugs, or financial innovations. But the same legalism that protects inventors and consumers also slows industrial-scale transformation; regulatory hurdles, litigation risks, and fragmented governance often delay the rollout of infrastructure, clean energy, and advanced manufacturing projects.

China’s engineering-centric model, on the other hand, enables sweeping transformations across physical and industrial systems. With a massive pool of engineers and a governance system that prioritizes technical expertise, China can mobilize talent and resources to build entire sectors at scale, from solar panels and high-speed rail to electric vehicles and 5G infrastructure. The result has been dramatic cost reductions in renewable energy technologies, vast improvements in infrastructure, and rapid gains in advanced manufacturing. However, this system falls short in fostering the kind of bottom-up, consumer-driven creativity that has powered U.S. leadership in areas like digital platforms, consumer products, pharmaceuticals and entertainment.

In essence, the United States excels at frontier innovation that reshapes consumer behavior and global culture, while China excels at systemic innovation that rebuilds industries and retools economies. The competition between these two paradigms is not just about who’s the most innovative, but about whose model will prove more effective at solving the complex, interconnected challenges of the 21st century: climate change, energy transition, global health, and technological governance.

Is America Ready for China’s Challenge?

America’s research universities remain unmatched, our entrepreneurial ecosystem is robust and our capital markets are deep. The country has repeatedly demonstrated resilience and an ability to mobilize when the stakes are high, whether in building the arsenal of democracy during World War II, landing on the moon, or pioneering the digital revolution. These assets are still very much alive and form the foundation of U.S. scientific and technological leadership.

But readiness today is increasingly blunted by structural frictions that act like bugs in the operating system of governance. America’s legal system, while essential for rights and accountability, often takes years or even decades to resolve conflicts, creating bottlenecks that stymie rapid adaptation. Policy continuity is undermined by sharp shifts across election cycles, where one administration’s priorities are dismantled by the next, making long-term planning increasingly difficult. Congress itself is hamstrung by deep divisions and procedural gridlock, which limit its ability to act decisively on major issues.

Practical execution is further slowed by permitting delays and fragmented standards, which can hold up infrastructure, energy, and manufacturing projects for years. The state-by-state nature of energy regulation, as example, adds another layer of complexity, making it difficult to coordinate a coherent national strategy. Immigration policies, once a cornerstone of U.S. scientific strength, are now clogged with bottlenecks and suspicion of foreign-born scientists, undermining the country’s talent advantage. Finally, culture-war polarization increasingly transforms science, climate, and education into partisan battlegrounds, eroding public trust and making consensus nearly impossible.

A key critique of the U.S. Congress is that it lacks the technical literacy to meet the demands of a world increasingly shaped by science and engineering. Lawyers make up roughly one-third of Congress, and businesspeople account for another large share, while only a handful of members have formal training in engineering or the natural sciences. This imbalance reflects America’s historical political culture, where law and commerce were considered the core skills for governance.

But this dynamic also creates a serious structural weakness for America’s future growth. In fields such as artificial intelligence, synthetic biology, quantum computing, renewable energy integration, and cybersecurity, policymaking depends on grappling with complex technical trade-offs that cannot be reduced to slogans or partisan talking points. without sufficient technical expertise in the legislature, lawmakers are often poorly equipped to grasp these complexities, leaving them unable to provide meaningful oversight or to shape independent, forward-looking policy.

America’s Resistance to 21st Century Technology

Compounding their lack of technical understanding in recent decades, American lawmakers have developed a profound resistance to the very technologies that will define the 21st century, a resistance that cannot be explained solely by economics or partisan politics. At its core, it is grounded in religious and ideological worldviews that shape how many leaders interpret humanity’s place in creation, the role of technology, and the purpose of government itself. Reinforced by partisan media and closely aligned with fossil fuel interests, these convictions have built a powerful cultural framework that consistently obstructs science-based policymaking.

At the foundation of this opposition lies a theological interpretation that sees environmental protection not as stewardship but as a challenge to divine order. Christian dominionist theology interprets the Genesis mandate as granting humans unrestricted authority to exploit the earth’s resources, while eschatological beliefs cast climate disruption as evidence of unfolding end-times prophecy rather than a crisis to be solved. According to a 2022 Pew Research Center survey, 63% of evangelical Protestants in the United States believe humanity is living in the end times, a conviction that profoundly shapes political attitudes. Within this framework, efforts to conserve ecosystems are often framed as a form of “deifying nature” and as an affront to the belief in human supremacy over creation.

This perspective gives rise to extreme political claims, with climate action being cast by some as the work of the Antichrist, while international agreements like the Paris Accord portrayed as stepping stones toward a one-world government foretold in Biblical prophecy. What was once fringe rhetoric has entered mainstream political discourse, exemplified by statements such as EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin’s vow to “drive a dagger straight into the heart of the climate change religion.” Evangelical broadcaster Jan Markell of Olive Tree Ministries has tied climate policy directly to apocalyptic prophecy, describing the UN- and Pope-backed “climate change agenda” as part of a plot to “usher in global government,” while insisting, “You and I know that God changes climate; we don’t change climate, God changes climate.” Historian Lisa Vox has noted that many conservative evangelicals believe “the Antichrist would use the fear of climate change to seize power,” reframing climate warnings as deceptive tools of prophecy. Prosperity gospel teachings further reinforce this worldview, portraying fossil fuel abundance not as an environmental danger but as a divine blessing bestowed upon humanity.

A parallel set of arguments shapes opposition to AI regulation and technological governance. Religious organizations, including the National Association of Evangelicals, resist federal frameworks out of concern that secular ethical systems will override Christian values. In June 2025, the National Academy of Engineering publicly opposed language in a reconciliation bill that would have imposed a federal moratorium on state AI regulation. The organization argued that such a restriction would improperly centralize power and limit the ability of states to protect citizens, reflecting a concern that federal frameworks or regulatory standards may sideline local or religious values, or embed secular ethical frameworks in ways Evangelicals see as a constraint on religious liberty. In this view, AI is not just a tool but a cultural battlefield: who defines its ethical boundaries, and on what moral foundation?

America’s democratic institutions are structured to reinforce these positions. White evangelical Protestants make up over a third of all Republicans, providing a powerful electoral base that ties theology directly to legislative outcomes. Religious broadcasters amplify these views, framing environmentalism and AI regulation as cultural identity threats. The generational divide is also telling: nearly four out of five young Republicans accept climate science, compared with less than half of those over 50, but it is the older cohort that dominates Congressional leadership. Fossil fuel industry influence then dovetails with religious justifications, creating a durable coalition that resists change.

The Science is Clear

These Congressional viewpoints persist even as the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) has affirmed that the evidence for human-caused climate change is now “beyond scientific dispute.” The Academies confirm that greenhouse gas emissions from human activity are unequivocally driving global warming and warn that many of the extremes we are witnessing today including prolonged heat waves, heavier rainfall, stronger storms will become the new normal if emissions continue unchecked. Importantly, the report stresses that climate change is not a distant or hypothetical concern; its impacts are already unfolding. Across the United States, communities are contending with record-breaking heat, shifting precipitation patterns, worsening air quality, and accelerating coastal flooding, each of which is straining public health, undermining infrastructure, and placing new burdens on local economies. In other words, climate change is no longer an abstract future threat but a present and growing reality, one that demands urgent, coordinated action.

These findings are reinforced by the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report, which confirms with unprecedented certainty that greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuel combustion, land-use change, and industrial activity are unequivocally driving global warming. The report makes clear that the physical science basis is no longer in doubt: areas of uncertainty that once allowed room for debate have been resolved or narrowed to the point of consensus. It warns that some impacts such as glacier retreat, ocean warming, sea-level rise, and the loss of fragile ecosystems will become irreversible if global temperatures cross critical thresholds. Overshooting the 1.5°C target above preindustrial levels, even temporarily, carries profound risks, from triggering feedback loops in the climate system to locking in widespread environmental degradation. The message is unambiguous: the window for avoiding the most dangerous and irreversible consequences of climate change is rapidly closing.

At the same time, the impact of these scientific findings on actual policy will hinge on whether the U.S. political system can overcome its structural impediments: deep partisan polarization, the distortions of short-term electoral cycles, inconsistent signals from competing federal agencies, and entrenched resistance from powerful vested interests. The clarity of the science is no longer in question; what remains uncertain is whether the United States possesses the political will and institutional capacity to translate that knowledge into decisive action commensurate with the scale and urgency of the climate crisis.

The current tensions over climate science and technological governance echo the struggles of the Enlightenment, when the rise of empirical inquiry challenged long-entrenched religious and political authority. In the 16th and 17th centuries, figures like Copernicus and Galileo faced fierce opposition from church leaders who viewed heliocentrism as heresy, just as today scientific consensus on climate change or artificial intelligence is resisted by groups who see it as a threat to faith, tradition, or existing power structures. The Enlightenment was ultimately about asserting that reason, evidence, and observation should guide human progress, providing an ethos that paved the way for modern science and democracy. Today’s disputes are a reminder that the tension between knowledge and belief, evidence and ideology, still remain a defining struggle of modern society.

What emerges is a sobering picture: America’s system, with its multiple veto points, magnifies the power of ideological blockages. The result is paralysis in the face of urgent challenges. Unlike governmental systems such as China’s, which tempers the power of various factions, allowing it to mobilize resources and talent toward systematic solutions, the U.S. Congress has become a battleground where religious identity, cultural politics, and industrial lobbying intersect to stall coordinated action. This contrast raises a fundamental question: can the United States modernize its policymaking framework to address the technological and environmental crises of the 21st century, or will entrenched ideology continue to blunt its capacity to act, and by default cede lasting global leadership to China?

What America is Up Against

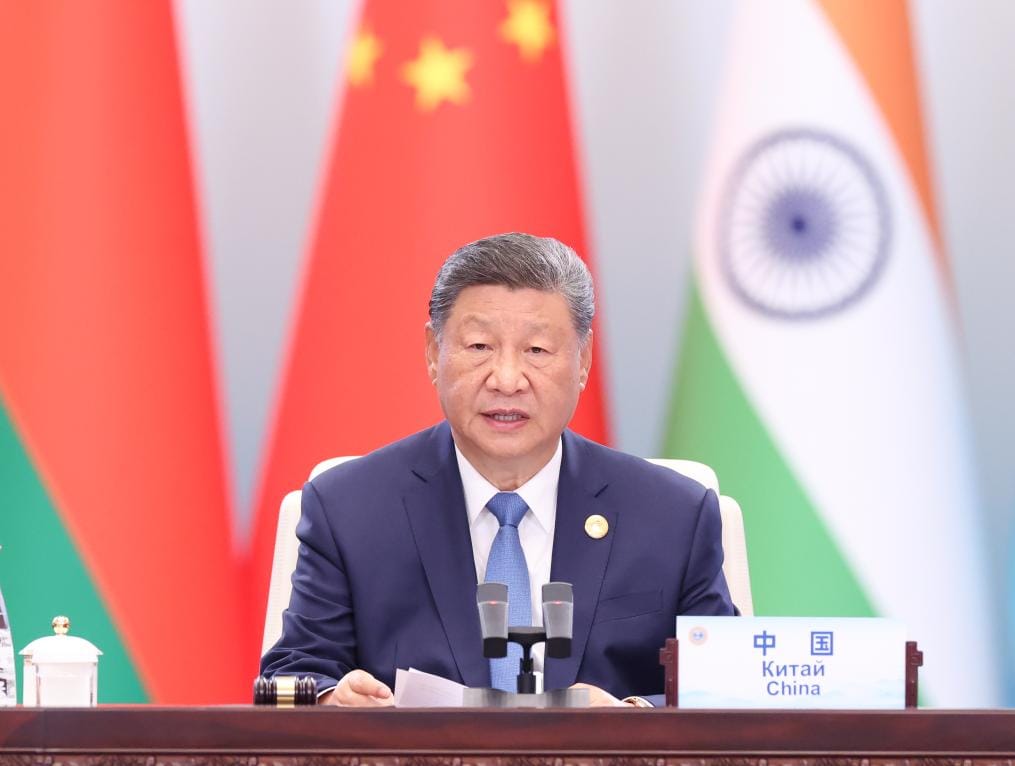

The contrast with China is stark. For decades, China’s leadership, both in the Politburo and at the provincial level, has been dominated by engineers, scientists, and technocrats. Their training in problem-solving and system design has made it easier for China to set long-term industrial policies, coordinate across sectors, and mobilize resources toward strategic goals such as renewable energy, semiconductors, and artificial intelligence. This engineer-led governance model allows China’s leadership to engage directly with technical questions and reduces dependence on outside experts for direction. By comparison, the U.S. Congress operates in a legalistic and precedent-driven manner, which is effective for adjudicating competing interests but slower and less adaptive when rapid technological change demands decisive and technically informed action.

This knowledge gap does not mean America cannot adapt, it still has world-class universities, research institutions, and a vibrant private sector, but it does suggest that the current composition of Congress is poorly suited to the realities of the 21st century. Unless the U.S. finds ways to integrate more scientific expertise into its legislative process, whether through recruiting candidates with technical backgrounds, strengthening advisory mechanisms, or expanding technical staff, it risks falling behind in shaping the policies that will govern the technologies defining the future.

China, by contrast, draws on centuries of meritocratic and pragmatic governance that has crystallized into a mentored meritocracy, engineer-led model of progress. This system elevates technical expertise, values rapid problem-solving, and prioritizes large-scale implementation. Instead of becoming mired in courtroom disputes, legislative gridlock, or endless public debate, China advances by piloting innovations in controlled settings, scaling them across entire cities, and weaving them into national strategy with remarkable speed and cohesion.

China’s political leadership has long been distinguished by its strong technocratic foundation. Within the Politburo, and especially its Standing Committee, a striking number of members have been trained in engineering, science, or other technical disciplines. This tradition dates back to the reform era, when leaders such as Hu Jintao, a hydraulic engineer, and Wen Jiabao, a geological engineer, rose to national prominence. Even Xi Jinping himself studied chemical engineering at Tsinghua University before pursuing law and political theory as part of his party advancement. Although recent years under Xi have brought a greater emphasis on ideological training, many of today’s senior leaders still carry the imprint of technical education and problem-solving backgrounds, which has shaped the pragmatism of Chinese governance.

This technocratic orientation extends deeply into the provinces. Governors and party secretaries frequently come from engineering or scientific fields. Research indicates that as many as two-thirds of provincial leaders during the reform era had backgrounds in engineering, economics, or related technical domains. Many began their careers in state-owned enterprises, research institutes, or major infrastructure projects, where they were expected to deliver measurable results. Their subsequent rise through the ranks was closely tied to China’s cadre evaluation system, which rewards tangible achievements such as GDP growth, infrastructure expansion, and poverty reduction.

Over time, this pattern created a leadership class that is steeped in technical expertise and managerial competence, in contrast to the United States, where political elites tend to come from law, business, or professional politics. While Xi Jinping’s consolidation of power has tilted the balance toward ideology and party loyalty, China still retains far more technocratic depth in its political system than other major powers. This background continues to influence how the country approaches innovation, governance, and large-scale implementation, embedding a culture of pragmatic, engineer-led problem-solving into its governing structures.

These two paradigms are far more than cultural curiosities; they represent fundamentally different visions of how societies create knowledge, adjudicate values, allocate resources, and confront the challenges of the age. The Western model prizes legal frameworks, negotiation, and precedent as the basis of governance, embedding innovation within a system that emphasizes rights, contracts, and procedural safeguards. By contrast, the Chinese model elevates technical expertise, rapid experimentation, and the capacity for large-scale implementation, channeling talent and resources into projects designed to achieve collective progress. The divergence is starkly illustrated in education: each year the United States produces roughly 140,000 engineering graduates, while China turns out more than 1.6 million. This disparity not only reflects differing cultural priorities but also reveals the depth of China’s technocratic orientation, suggesting a society that views engineering talent as a strategic resource essential to national development and global competitiveness.

Tracing their respective historical and philosophical origins reveals how these models evolved and why they diverge so sharply. Comparing their influence on breakthrough innovation in critical sectors, from energy and infrastructure to digital technology and biotechnology, underscores how each system translates ideas into action. Ultimately, the central question is which model is better positioned to navigate the interdependent crises of the 21st century, from climate change to technological disruption, where speed, scale, and systemic coordination may prove decisive.

Contrasting Philosophical and Cultural Foundations: Confucianism vs. Christianity

The divergent paths of American and Chinese innovation are not simply the outcome of modern policy decisions, but the culmination of centuries of contrasting philosophical and religious traditions that have molded their cultures, governance systems, and legal frameworks. In the United States, the Judeo-Christian heritage, shaped most powerfully by Protestant Christianity, nurtured a society that elevates the individual, codifies rights and responsibilities through law, and resolves disputes within a legalistic framework. By contrast, China’s 2,500 year foundation in Confucian thought established an ethical and political order that prizes hierarchy, meritocracy, and collective harmony, embedding a pragmatic orientation toward governance and social organization. These deep-rooted traditions continue to inform how each nation conceives of progress, authority, and the role of innovation in society.

The Influence of Christianity on Western Legalism and Individualism

The Protestant Reformation, with its insistence on the individual’s direct relationship with God, helped establish the intellectual foundation for America’s concept of individual rights and responsibilities. This theological transformation profoundly reshaped legal and political thought, embedding the idea that all individuals are equal before God and, by extension, equal before the law. The emphasis on conscience and moral agency cultivated a culture that prioritized autonomy and personal rights, principles that would later be codified in Western legal systems, constitutions, and democratic institutions. Christianity’s influence can also be seen in the evolution of legal norms such as due process, the presumption of innocence, and the expectation that law is grounded in a moral order. Biblical texts, particularly the Ten Commandments, reinforced prohibitions against theft, murder, and false testimony, while the concept of “natural law” advanced the belief in universal moral principles transcending human authority. Together, these legacies created a legal tradition that ties justice not only to human institutions but also to higher, divinely inspired moral standards, shaping the very framework of Western governance.

From the Catholic Church perspective, natural law is the cornerstone of legal and moral order. Drawing from thinkers like St. Thomas Aquinas, the Church teaches that natural law is accessible through human reason and reflects God’s eternal law. Every person, regardless of faith, can discern basic moral truths: prohibitions against murder, theft, or perjury because they are written into the human heart. Law, therefore, must be grounded in this objective moral order. Catholic tradition also emphasizes the common good: the purpose of law is not only to protect individual rights but also to guide society toward justice, harmony, and ultimately God. An unjust law that contradicts natural law, in this view, lacks true authority. This explains why Catholic thought historically tied justice to both reason and divine order, insisting that rulers themselves are accountable to a higher moral law.

The Protestant tradition, by contrast, places a stronger emphasis on the individual’s direct relationship with God and on Scripture as the primary source of authority. The Protestant Reformation shifted the center of gravity from a universal, reason-based natural law toward biblical authority and individual conscience. This had profound legal implications: it nurtured a culture of individual rights and responsibilities, framing the law as a safeguard of personal liberty before both God and the state. Equality before God became equality before the law; the sanctity of individual conscience helped foster legal principles such as freedom of religion, the presumption of innocence, and due process. Where Catholicism stressed a universal moral order binding rulers and communities, Protestantism leaned toward individual autonomy and contractual relationships, encouraging the development of legal frameworks that protect personal freedom and regulate society through codified rights and obligations.

In essence, Catholic legal thought emphasizes natural law and the common good, while Protestant legal thought emphasizes individual conscience and rights. Together, these streams merged into the Western legal tradition, but they left distinct marks: Catholicism grounding law in an eternal moral order, Protestantism championing personal liberty and equality before the law.

The fact that six of the current U.S. Supreme Court’s conservative justices are Catholic (John Roberts, Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Brett Kavanaugh, Amy Coney Barrett, and Neil Gorsuch was raised Catholic, raises interesting questions about the court’s trajectory, as Catholic intellectual tradition carries distinctive emphasis that can shape legal interpretation, even when applied in a secular court.

At its core, Catholic legal thought emphasizes that law is not simply a set of human-made rules or procedural norms, but as something that must align with a higher, universal moral order accessible through both reason and faith. In practice, this orientation often translates into a judicial philosophy that seeks to anchor legal decisions in enduring moral principles rather than purely pragmatic or utilitarian calculations. It can also incline judges toward skepticism of expansive judicial “innovation” if such innovation seems to deviate from what they see as the natural law foundations of justice.

Legalism, Religious Liberty and Scientific Inquiry

This legalistic and individualistic tradition of the United States has produced a society that prizes personal achievement, competition, and increasingly the safeguarding of religious liberty. The rise of the Religious Right in the 1970s and 1980s, galvanized by debates over school prayer, abortion, and the Equal Rights Amendment, brought religious liberty to the center of cultural and political identity in America. Court cases like Employment Division v. Smith (1990) narrowed protections under the Free Exercise Clause, but Congress responded with the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (1993), reflecting bipartisan consensus at the time that religious liberty should be robustly defended. Since then, the issue has only intensified, with disputes over public health mandates (especially during the COVID-19 pandemic), LGBTQ+ rights (Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission, 2018), and the use of public funds for religious schools (Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue, 2020).

At the political level, this emphasis has led to a powerful alliance between religious constituencies and legislators who view the protection of religious liberty as paramount, even when it comes into conflict with broader social or scientific policy goals. The persistence of debates over issues such as AI regulation, climate action, or reproductive rights often reflects this deeply ingrained tendency: individuals and groups turn to the courts or legislative protections to carve out exemptions based on conscience and belief. In this sense, the safeguarding of religious liberty illustrates how America’s legalistic and individualistic culture channels even questions of collective policy into a framework defined by personal rights, judicial precedent, and adversarial contestation, rather than by collective solutions.

By contrast, China’s governance model, shaped by Confucian traditions of hierarchy, meritocracy, and collective harmony takes a fundamentally different approach. Rather than framing policy in terms of individual exemptions or rights claims, the Chinese system prioritizes collective order, stability, and pragmatic solutions. In areas such as environmental regulation or technology deployment, decisions are made with an emphasis on long-term societal benefit, rapid implementation, and system-level coherence. The Confucian legacy encourages citizens to see themselves as part of a social hierarchy with defined roles and obligations, rather than as individuals seeking exemptions from collective rules. This cultural and institutional orientation enables China to mobilize resources and align institutions behind ambitious projects, whether in renewable energy, infrastructure, or AI, without the kinds of fragmentation and legal contestation that characterize the American system.

In essence, while the U.S. channels debates over science, technology, and social change into rights-based legal battles that can take years to decades to resolve, China relies on technocratic pragmatism and collective discipline to move swiftly. Both systems have strengths: America excels at protecting diversity of thought and individual conscience, while China is better positioned to implement large-scale solutions. But in a century to be defined by climate change, AI, and global competition, this divergence raises a critical question: can the U.S. adapt its legalistic framework to deliver systemic action at scale, or will it remain constrained by the very individualism that has long been its strength?

Dynamic Balance Between the Common Good and Individual Liberty

The dynamic tension between the common good and individual liberty is a universal feature of governance, present across cultures, systems, and historical eras. On one side lies the state’s obligation to promote stability, security, and prosperity for the collective, which often requires coordinated action, resource pooling, and sometimes the restriction of personal freedoms. On the other side lies the individual’s claim to autonomy, conscience, and choice, the right to resist overreach, challenge authority, and pursue one’s own vision of the good life. This tension cannot be eliminated; it is built into the human condition. The question is always how it is managed and where the balance is struck.

History demonstrates that when either pole dominates, the system falters. Stability depends on maintaining a dynamic balance, with a strong enough belief in institutions to coordinate collective action, yet flexible enough to preserve individual freedoms, creativity, and adaptation. This balance is not static; it shifts with circumstances. In times of war or natural disaster, societies often lean toward the common good; in times of peace and prosperity, they may tilt toward personal liberty. The danger arises when adherents of extreme views, whether totalizing statism or radical individualism gain control and harden the system against correction. In such cases, the very challenges societies must address can become unmanageable, leading to systemic collapse.

Can America’s Extreme Polarization Be Reframed

The resistance among many members of the U.S. Congress to addressing the most pressing issues of our time such as climate change, artificial intelligence regulation, and renewable energy cannot be reduced to narrow policy disagreements. It is instead the product of a complex web of religious, ideological, and economic motivations that mirror the deeper cultural divisions within American society. These positions are not simply about the cost of regulations or the scope of government action; they are grounded in broader worldviews that shape how lawmakers interpret humanity’s place in creation, the role of technology in society, and the legitimacy of government authority.

This dynamic is most visible in climate policy. Today, 28% of the 118th Congress openly deny the scientific consensus on human-caused climate change, a remarkable figure given the overwhelming body of scientific evidence. This bloc represents more than skepticism about science. It reflects a philosophical position deeply tied to religious convictions about dominion over nature, economic ties to the fossil fuel industry, and ideological fears of global governance. To many of these legislators, climate action is not just misguided policy; it is seen as a direct challenge to deeply held beliefs about freedom, divine order, and America’s sovereignty. In this sense, the debate is less about parts per million of carbon dioxide and more about competing worldviews, making compromise far more difficult to achieve.

Some evangelical leaders have gone so far as to frame environmental protection as a theological threat, arguing that conservation efforts amount to an attempt to “deify nature” in violation of Christian principles that place humanity above the natural world. This perspective has found political expression in Congress, reflected in statements such as EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin’s vow to drive “a dagger straight into the heart of the climate change religion.” Beneath this rhetoric lies a powerful eschatological dimension: for many believers, environmental degradation is not a crisis to be solved but a sign of biblical prophecy being fulfilled. Climate disruption, in this view, is a necessary precursor to Christ’s second coming, which makes mitigation efforts not only futile but even contrary to divine will.

The scale of this conviction is striking. According to a 2022 Pew Research Center survey, 63% of evangelical Protestants in the United States believe that humanity is living in the end times. As historian Lisa Vox has shown, this eschatological framework leads many conservative evangelicals to interpret climate science not as empirical evidence but as a deception orchestrated by the Antichrist. Warnings about global warming are thus recast as tools of fear meant to advance a one-world government that will set the stage for the seven-year Tribulation described in the Book of Revelation. When this theological worldview is translated into legislative action, it creates not just resistance but an entrenched moral opposition to climate policy, making bipartisan compromise on environmental issues extraordinarily difficult.

This apocalyptic framework has led to Congressional opposition to international climate agreements like the Paris Accord, which are viewed as stepping stones toward the prophesied one-world government that will herald the end times. The political appeal of this narrative has been amplified by the Trump administration's framing of climate action as an existential threat to American sovereignty, resonating with evangelicals who maintain significant influence over GOP policy positions.

Religious Opposition to AI Regulation

Opposition to artificial intelligence regulation among Congressional Republicans reflects many of the same religious and ideological concerns that shape resistance to climate policy. At its core lies a deep suspicion of government overreach and a conviction that decisions about technology should not erode traditional understandings of human authority. For religious conservatives in particular, AI raises alarm because it inevitably requires embedding ethical and moral frameworks into systems that make or influence decisions. If those frameworks are established at the federal level, many fear they will reflect secular or progressive values that conflict with Christian teachings.

This concern is not abstract. Conservative lawmakers and religious organizations have pointed specifically to issues of gender, sexuality, family structure, and the sanctity of life as areas where secular AI standards could directly clash with their beliefs. For instance, they worry that algorithms guiding healthcare recommendations, content moderation, or employment screening might enshrine values that contradict traditional understandings of morality, forcing religious individuals or institutions to operate within systems that undermine their convictions. The fear is not just that AI could “think” in secular terms, but that federal regulation would lock those terms into law, effectively sidelining religious perspectives in domains ranging from bioethics to education.

As a result, many Republicans in Congress have resisted efforts to create comprehensive federal frameworks for AI governance, preferring instead to leave regulation fragmented or limited to narrow applications. This stance preserves space for religious communities to assert their own moral authority over how AI is used in schools, churches, businesses, and medical institutions. However, it also means the U.S. risks being left behind in establishing global standards for algorithmic transparency, safety, and accountability issues that will shape not just the economy but the ethical landscape of the 21st century.

Europe’s Secular Path

The contrast with Europe is especially revealing. While U.S. lawmakers have resisted comprehensive AI governance frameworks out of fear that federal standards would enshrine secular values over religious ones, the European Union has moved decisively in the opposite direction. In 2024, the EU finalized its AI Act, the world’s first comprehensive legal framework for artificial intelligence. The law establishes clear rules around algorithmic transparency, bans certain high-risk applications such as social scoring, and mandates ethical safeguards in areas like biometrics, consumer protection, and labor rights. Importantly, the EU frames these rules within a secular, rights-based ethical tradition rooted in human dignity, privacy, and non-discrimination.

This divergence underscores the tension at the heart of the American debate. For many conservative lawmakers in the U.S., the fear is that adopting EU-style regulation would embed secular ethical assumptions, for example, on gender identity, sexuality, or reproductive rights that conflict with their religious moral frameworks. Where Europe sees the regulation of AI as a way to ensure fairness and protect citizens in line with universal human rights principles, U.S. opponents worry such standards would override local values, religious liberty, and parental authority. This cultural and religious resistance has left the U.S. with a fragmented, patchwork approach: state-level initiatives, industry self-regulation, and sector-specific guidelines instead of a unified federal standard.

The result is that while Europe positions itself as the global rule-setter for AI ethics, the U.S. is currently paralyzed by ideological divisions. Religious concerns about government overreach and secular moral dominance continue to stall national action, leaving America’s AI governance landscape vulnerable to both corporate capture and international marginalization. In short, Europe is exporting its values into the very DNA of global AI standards, while the U.S. is still fighting over whether embedding values at all is legitimate.

China’s State-Driven Path

Adding China to the comparison makes the global divide over AI governance even clearer. While Europe builds its AI framework around secular human rights and the U.S. struggles with religious and ideological resistance to centralized standards, China has pursued an entirely different path: one rooted in state authority, social stability, and geopolitical advantage.

China’s regulatory model reflects its broader state-managed governance system. Instead of debating whether values should be embedded into AI, Beijing assumes that values are always embedded, and that those values must align with Party priorities. Regulations released by the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) in 2022 and 2023 explicitly require AI systems to promote “core socialist values,” avoid generating content that undermines state authority, and submit algorithms for government review. These rules focus less on abstract questions of rights or liberty and more on ensuring that technology remains a tool of social cohesion and overall national strength.

China’s AI governance also serves a strategic function in global competition. By tightly coordinating between government, academia, and industry, Beijing is able to set technical standards, direct funding toward strategic applications, and accelerate deployment in areas like surveillance, smart cities, and military technologies. Unlike the U.S., where regulation is fragmented, or Europe, where regulation emphasizes ethical constraint, China’s model prioritizes rapid implementation and scale, at the expense of open-ended inquiry.

Thus, the world’s three major power centers are shaping AI governance in fundamentally different ways: Europe seeks to anchor AI in human dignity and rights; the United States is gridlocked by a cultural battle between secular governance and religious liberty; and China treats AI regulation as an extension of state strategic planning. The result is a fractured global landscape where values, ideology, and political systems, not just technical capability, determine how one of the century’s most transformative technologies will evolve.

Fossil Fuels as a Divine Blessing

Renewable energy opposition among Congressional Republicans combines religious justifications with economic and ideological arguments rooted in free-market fundamentalism and fossil fuel industry influence. The theological component draws from prosperity gospel teachings that interpret material abundance, including energy abundance from fossil fuels, as evidence of divine blessing and favor. This framework views renewable energy transitions as potentially contrary to God's provision of fossil fuel resources, with some evangelical leaders arguing that oil, coal, and natural gas represent divine gifts that humans are obligated to utilize rather than abandon. The Cornwall Alliance, a conservative Christian organization, has explicitly argued that free-market approaches to energy development represent proper Christian stewardship, while government-mandated renewable energy transitions constitute improper interference with divine providence.

The intersection of religious beliefs with fossil fuel industry influence in the United States creates a powerful coalition that shapes Congressional opposition to renewable energy initiatives. Many Republican lawmakers represent districts with significant fossil fuel employment and receive substantial campaign contributions from oil, gas, and coal companies, creating economic incentives that align with religious justifications for opposing renewable energy transitions. This convergence enables lawmakers to frame their opposition in moral and theological terms while serving concrete economic interests, as seen in Congressional statements that characterize renewable energy mandates as attacks on traditional American values and energy independence.

During debates over the Green New Deal, several members of Congress denounced renewable energy mandates as a “Trojan horse for socialism,” warning that they would undermine “God-given” American freedoms and destroy fossil fuel jobs that communities depend on. Similarly, in hearings on federal energy policy, some legislators have argued that attempts to phase out coal and oil amount to “an assault on our way of life,” casting fossil fuels not just as an economic necessity but as a symbol of American strength and divine providence. By blending theological rhetoric with appeals to energy independence, these lawmakers reframe resistance to renewable energy as both a moral duty and an act of patriotism, that coincidently aligns with the interests of the fossil fuel industry.

The legalistic culture that characterizes American governance amplifies these religious and ideological objections by providing multiple institutional mechanisms for blocking or delaying policy initiatives. The complex regulatory framework, multiple levels of government authority, and extensive judicial review processes create numerous opportunities for a minority of opponents to block climate action, AI regulation, and renewable energy policies through legal and procedural means.

Minority Rule and The Fight for Traditional Values

Congressional opposition also reflects broader cultural anxieties about technological change and social transformation that resonate with religious conservative constituencies. Climate action, AI development, and renewable energy transitions are often perceived as components of a broader secular progressive agenda that threatens traditional values and what is framed as ‘the American way of life.’ “The American Way of Life” is often cast defensively, as something endangered by progressive cultural change, whether through immigration, environmental regulation, or evolving norms around gender and sexuality. Conservatives present themselves as guardians of this way of life, preserving it for future generations. This perception is reinforced by the association of these issues with urban, educated, and secular demographics that are often viewed with suspicion by rural and religious conservative communities.

Because of the structure of the U.S. political system, which grants disproportionate representation to rural states in the Senate and shapes House districts through rural weighting, a majority of members of Congress are drawn from or rely heavily on rural constituencies. This amplifies the influence of cultural conservatism in national policymaking. The result is Congressional resistance that goes beyond specific policy objections to encompass broader cultural and identity-based opposition to the social groups and institutions promoting these technological and environmental initiatives.

The influence of religious broadcasting and conservative media in shaping Congressional positions cannot be understated as well, as these platforms regularly frame climate science, AI development, and renewable energy as threats to Christian values and American sovereignty. This media ecosystem creates strong political incentives for Republican lawmakers to maintain opposition positions, as deviation from these stances can result in primary challenges from more conservative candidates who question their religious and ideological purity. The result is a self-reinforcing cycle where Congressional opposition becomes increasingly entrenched and resistant to scientific evidence or changing public opinion.

The age demographics within the Republican Party reveal significant generational tensions that may eventually reshape Congressional positions on these issues. Younger Republicans are far more likely to accept climate science and support renewable energy development, with 79% of Republicans ages 18-29 acknowledging that human activity contributes to climate change, compared to a minority of Republicans over 50. However, the current Congressional leadership and primary voting patterns remain dominated by older, more religiously conservative constituencies that maintain strong opposition to climate action and renewable energy transitions.

This religious and ideological opposition to climate action, AI regulation, and renewable energy poses a profound challenge to America’s ability to confront the technological demands of the 21st century. The U.S. legalistic and market-driven system offers essential safeguards, protecting individual liberty, religious freedom, and minority rights, but those same strengths can become weaknesses when facing crises that require rapid, large-scale mobilization. The very mechanisms intended to curb government overreach and safeguard pluralism also multiply veto points that bypass majority rule, splinter authority, and open endless pathways for litigation, rendering coordinated national action extremely difficult.

As a result, America’s governance framework often excels at slowing things down, ensuring debate, but it struggles to translate majority preferences into decisive policy or to marshal resources in a unified way. This stands in sharp contrast to state-led systems, which, though much less protective of individual rights, are better equipped to align government, industry, and society around ambitious projects like decarbonization, digital infrastructure, or advanced manufacturing. The danger for the United States is that, without adapting its institutions, it risks remaining trapped in a cycle of paralysis, well defended against governmental overreach but poorly positioned to seize opportunities or meet existential challenges that demand speed, scale, and systematic coordination.

The Scope and Intensity of America’s Technological Anxiety

Religious anxiety has long accompanied the adoption of new technologies in the United States, even if it has not always been the dominant force shaping public acceptance. What distinguishes the current wave of resistance to technologies like climate change mitigation and artificial intelligence is not the mere presence of religious anxiety, which has always been part of America’s technological story, but its scope and intensity. Earlier objections tended to be local, cultural, or rooted in fears of social disruption, and they faded as the technologies proved useful. Today, however, opposition is more systematic, with organized religious movements tying climate action and AI regulation directly to theological worldviews.

Beliefs rooted in dominion theology, end-times prophecy, and concerns about secular moral frameworks frame these technologies not just as disruptive, but as existential threats to divine order and religious liberty. Unlike past anxieties, which largely adapted once technologies became embedded, today’s religious resistance has become deeply entwined with partisan politics, fossil fuel interests, and cultural identity battles transforming it into a powerful and likely enduring obstacle to science-driven policymaking.

The Role of the Conservative Media Ecosystem

What truly intensifies this dynamic today is the role of the internet, podcasting, and platforms like YouTube in amplifying and hardening these narratives. Earlier waves of technological anxiety circulated mainly within local communities or through denominational networks, meaning they were often tempered by proximity, debate, or eventual exposure to the practical benefits of new technologies. In contrast, today’s digital ecosystem allows religious and ideological framings of climate action and AI regulation to circulate instantly to millions, often stripped of nuance and reinforced by algorithmic recommendations. Podcasts, livestreams, and YouTube channels hosted by pastors, political commentators, and self-styled “truth-tellers” create echo chambers where claims that climate action is anti-Christian or that AI is a secular attempt to usurp God’s role are repeated and validated.

These platforms have become powerful tools for identity formation, knitting together audiences who share not just religious convictions but a worldview that interprets environmentalism, technological governance, and global cooperation as coordinated threats to faith and freedom. Because the internet bypasses traditional gatekeepers, such as mainstream media, or academic experts, who are often viewed as enemies of the truth by conservatives, it empowers voices on the margins who frame resistance in apocalyptic or conspiratorial terms. The result is that opposition to science-driven policymaking is no longer a diffuse or fading sentiment but a sustained, networked movement with its own media ecosystem.

According to a 2024 analysis by Media Matters for America, right-leaning media dominates much of the online talk and podcast space, with conservative shows commanding nearly five times the following of their left-leaning counterparts. In fact, eight of the ten most-followed online shows were conservative, together reaching an estimated 197 million listeners. Right-wing media command such large audiences in part because of how their content, values, and structure resonate with their target audience. One major factor is the emotional intensity of the content. Conservative talk shows and podcasts are often built around anger, fear, pride, and grievance, emotions that are powerful drivers of attention and loyalty. By framing issues like climate action, immigration, or cultural change as existential threats to “the American way of life,” conservative media generate a sense of urgency and personal investment that keeps audiences coming back.

Another reason is that conservative outlets tend to offer clear, identity-affirming narratives. For many listeners, right-leaning shows do more than deliver news; they provide moral frameworks that align with deeply held values around patriotism, religion, traditional family structures, and individual freedom. This creates a sense of belonging and validation, especially for audiences who feel alienated or dismissed by mainstream media. By reinforcing these shared identities, conservative personalities cultivate not just listeners but communities of belief.

The structural concentration of conservative media further amplifies its reach. Unlike liberal or mainstream outlets, which are more fragmented across many publications and platforms, right-wing audiences are clustered around a relatively small number of highly influential voices, radio hosts, podcasters, and video commentators whose messages dominate the ecosystem. This concentration creates a powerful echo chamber effect, where narratives are repeated, amplified, and reinforced across multiple platforms, producing both consistency and intensity.

Finally, conservative media often thrive on a countercultural appeal, positioning themselves as alternatives to “elitist” or “biased” mainstream sources. By tapping into distrust of institutions, they turn skepticism into loyalty: consuming right-wing media is framed not just as entertainment, but as a political act of resistance. Combined with savvy use of digital platforms like YouTube, Facebook, and podcasting apps, this dynamic helps conservative media dominate the online space, both in audience size and cultural influence.

A Pew Research Center study highlights a stark divide: while liberals report high levels of trust in legacy newspapers like The New York Times and in major television networks, conservatives tend to distrust most mainstream media, relying instead on explicitly ideological sources. This divergence has created two very different media cultures, one in which conservatives cluster around a handful of high-reach platforms, and another in which liberals draw from a broader, more diffuse mix of outlets. The result is a conservative media ecosystem with remarkable scale and coherence, capable of amplifying narratives rapidly and deeply into its audience, while liberal media consumption remains more pluralistic but less concentrated in influence.

The concentration of the conservative media ecosystem has profound implications for how narratives about climate change, AI regulation, and renewable energy are received and reinforced. Because a relatively small number of high-reach outlets dominate conservative audiences, messages that frame climate action as an attack on the “American way of life” or portray AI regulation as a vehicle for secular values can spread rapidly and achieve remarkable staying power.

In contrast, the more diffuse liberal media ecosystem, anchored in mainstream outlets such as The New York Times, NPR, or major television networks operates on a very different logic. These outlets prioritize detailed policy coverage, investigative reporting, and nuance, offering audiences a wide array of perspectives rather than a singular, unifying narrative. On issues like climate science, technology policy, or renewable energy, the reporting is typically robust and evidence-driven, but because it emphasizes complexity and multiple viewpoints, it lacks the emotional clarity and identity-based framing that characterize conservative media.

This structural pluralism means that no single narrative or call to action dominates liberal media in the way it does on the right. Instead, audiences are spread across different sources and interpretive frameworks, diluting the cultural cohesion and intensity of any one message. As a result, pro-climate and pro-regulation arguments, while scientifically well-supported, often struggle to achieve the same resonance as conservative narratives that cast these policies in stark, emotionally charged terms of threat or identity. The outcome is an asymmetry: liberal media supply facts and nuance, but conservative media generate the kind of emotional mobilization that translates more readily into loyalty, activism, and political influence.

This asymmetry helps explain why conservative opposition to climate action and AI governance remains so entrenched. In conservative media spaces, skepticism is consistently reinforced by a tightly knit echo chamber that connects religious convictions, partisan identity, and fossil fuel interests into a coherent worldview. Meanwhile, in liberal spaces, support for science-driven policymaking competes with multiple priorities, making it harder to mobilize with the same intensity. The net effect is that conservative media concentration amplifies resistance, while liberal media plurality dilutes advocacy, creating a lopsided communication landscape that shapes the national debate on the technologies most critical to America’s future.

Conservative media outlets like Fox News and talk radio hosts frequently frame the Paris Accord not as a cooperative effort to address a global crisis but as an assault on U.S. sovereignty. It is portrayed as a “globalist scheme” that forces America to sacrifice its economic strength while letting China and developing nations pollute freely. Commentators often link it to Biblical prophecy about one-world government, echoing evangelical claims that international agreements are steps toward an Antichrist-led system of global control.

Right-leaning podcasts and YouTube channels have consistently attacked the Green New Deal as a socialist Trojan horse designed to upend the American way of life. Conservative pundits describe it as an elite-driven project by secular urban progressives to tell ordinary Americans what cars they can drive, what food they can eat, and how they can heat their homes. Some religious broadcasters go further, suggesting that the push for radical environmental policy represents a false religion that elevates nature above humanity’s God-given dominion.

Conservative media often casts wind and solar energy not simply as economically unviable but as symbols of cultural identity battles. Wind farms are framed as desecrating “God’s land” or threatening rural traditions, while subsidies for renewables are condemned as punishments for hardworking fossil fuel workers. The abundance of oil, coal, and gas is often described as a divine blessing, reinforcing the idea that moving away from them is both economically reckless and spiritually misguided.

Emerging narratives in conservative podcasts and evangelical forums frame AI regulation as a secular imposition that could embed anti-Christian values into the technology itself. Concerns are raised that federal standards could require algorithms to affirm positions on gender, sexuality, or bioethics that conflict with biblical teachings. This framing transforms technical governance debates into existential moral struggles, making resistance to regulation a defense of religious liberty.

Taken together, these examples show how conservative media does more than argue policy. It moralizes and spiritualizes technological debates, embedding them within broader narratives about sovereignty, freedom, religious identity, and divine order. That framing helps explain why opposition in Congress is so deeply entrenched: lawmakers are not simply weighing policy trade-offs but defending what their constituents see as cultural and spiritual red lines.

In this sense, social media does more than communicate information; it solidifies political divides by aligning religious anxiety with partisan identity and economic interests, reinforcing the perception that climate policy and AI regulation are not technical debates but existential battles. Unlike in earlier eras, where skepticism diminished once technologies proved useful, today’s media landscape ensures that resistance will persist, grow, and organize long after the evidence of utility is clear, transforming cultural anxieties into enduring political obstacles.

The Cost of Being Lost in a World of Alternate Realities

One particular group that has been highly impacted by the conservative media ecosystem is young men, who often find themselves searching for identity and meaning in an era of “alternate facts” and competing realities. With traditional pathways to adulthood such as steady employment, clear community roles, and broadly shared cultural narratives becoming increasingly fractured, young men are left navigating uncertainty about their place in society. Conservative digital media platforms step into this vacuum, offering not just information, but belonging and purpose. Through podcasts, YouTube channels, and social media networks, they provide ready-made identities, moral frameworks, and communities that validate feelings of anxiety, alienation, or frustration.

These platforms frame personal struggles within a larger cultural or spiritual battle, transforming private insecurities into a sense of participating in a collective mission. For young men in particular, this can be profoundly attractive: instead of being isolated individuals adrift in a rapidly changing world, they are cast as defenders of faith, freedom, and tradition against the perceived encroachments of secular progressivism, globalism, or technological overreach. In this way, conservative media doesn’t just shape political opinion but provides a narrative of significance that helps young men feel seen, empowered, and part of something larger than themselves.

For young men trying to locate their role in a world of rapid technological change, climate disruption, and shifting cultural norms, these ecosystems can feel like lifelines. They frame complex issues like climate policy or AI regulation not as technical debates, but as epic struggles over freedom, faith, and national identity. By casting these conflicts as existential battles, conservative podcasts, YouTube channels, and social media groups transform uncertainty into clarity, providing young men with a sense of significance: they are not just individuals searching for their place, but warriors defending a way of life.

The appeal lies in this combination of certainty, community, and mission. At a time when mainstream institutions are often perceived as fragmented, untrustworthy, or hostile to traditional masculinity, these alternative media spaces offer a coherent story about who young men are, what they should value, and why their voices matter. In this way, the pull of partisan digital ecosystems is not primarily informational but existential: they supply the identity and meaning that many young men feel has been eroded in a rapidly changing world.

These Compelling Narratives are not New

This pattern of young men gravitating toward identity-shaping movements in moments of upheaval is not new; it echoes earlier historical periods when rapid change left individuals searching for belonging, clarity, and purpose. In the early 20th century, for instance, militarism and nationalism offered young men in Europe a compelling narrative of honor, sacrifice, and collective destiny at a time when industrialization and urbanization were uprooting traditional social structures. The appeal of marching in uniform, defending the nation, or participating in empire-building gave young men a role larger than themselves, one that promised meaning in a disorienting modern world.

Similarly, in times of social fragmentation, religious revival movements have provided young men with identity and purpose. During the Second Great Awakening in the United States in the early 1800’s, revivals swept through communities offering certainty, moral order, and a chance to channel youthful energy into spiritual struggle and communal renewal. For many, these movements substituted for the stability that economic or political structures could not provide, transforming personal anxieties into a larger story of cosmic importance.

Today’s digital media ecosystems function in much the same way, but with unprecedented speed and reach. Where militarism once offered a uniform and a battlefield, podcasts and YouTube channels now provide ideological uniforms and virtual battlefields. Where religious revivals once gave young men the sense of being soldiers in a divine struggle, today’s digital platforms frame them as defenders of faith, freedom, and truth against secular elites, globalists, or technological threats. In each case, the common thread is clear: young men seek meaning through narratives that elevate their personal struggles into part of a larger, transcendent fight.

How is China’s Culture Reacting to This Period of Uncertainty

China’s social and political structure does provide young people with a very different kind of environment than their peers experience in the United States, one that is designed to buffer them from the full force of modern social disruption and the “alternative realities” so visible in America. Rooted in Confucian traditions that prize social harmony and collective well-being over individualism, China’s governance model is oriented toward stability and continuity. The state actively curates the media environment, regulates cultural content, and monitors online discourse, seeking to limit exposure to the kind of disinformation, conspiracy theories, and ideological fragmentation that have destabilized Western democracies. This emphasis on continuity and order helps shield young people from the chaotic churn of competing narratives that often define youth identity in America’s polarized digital ecosystem.

Although the CCP is rife with internal competition and deep factional maneuvering, it consistently presents itself to the public as a custodian of collective harmony rather than an arena for partisan conflict, as contending political parties do in the United States. For young people in China, this means their ambitions are framed in terms of national development priorities, academic success, technological achievement, and upward social mobility rather than through the fractured cultural debates and existential uncertainties that often confront American youth. In this sense, China’s system partially shields its younger generations from the disorienting effects of competing “alternative realities” and the identity fragmentation characteristic of the U.S. media environment.

In essence, the structure of Chinese society does offer its young people greater insulation from destabilizing forces, but this insulation is achieved through top-down management of culture, information, and public life. Where America’s youth navigate a landscape of competing truths and fractured meaning, Chinese youth grow up in a more curated system that prioritizes collective stability and national cohesion.

One of the clearest media contrasts between China and the United States lies in digital governance, which plays a decisive role in shaping how young people experience modernity, social disruption, and alternative realities. In China, the “Great Firewall” and a comprehensive system of internet regulation create a curated digital environment. Foreign platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube are blocked, while domestic platforms such as WeChat, Weibo, Douyin, and Bilibili operate under strict state oversight. Content that could fuel political dissent, spread conspiracy theories, or undermine social cohesion is filtered or removed, and algorithms are required to align with state objectives. For young people, this means their online environment is not the cacophony of clashing narratives seen in the West, but one shaped to reinforce national priorities, cultural continuity, and collective identity.

By contrast, the United States has embraced a laissez-faire digital landscape, where social media platforms are largely self-regulated and open to all forms of speech. While this openness reflects America’s tradition of individual liberty, it also exposes young people to disinformation, culture wars, and ideological echo chambers. Platforms like YouTube, TikTok, and podcasts often amplify polarizing voices, producing fragmented “alternative realities” that pull communities apart and leave young men in particular searching for meaning in highly partisan or conspiratorial media ecosystems. Instead of curated stability, American youth face an overabundance of competing truths, where identity and belonging are often forged in opposition to perceived enemies.

The result is that Chinese digital governance insulates youth from much of the turbulence that characterizes American online life, while American openness allows for greater diversity of voices but also far more vulnerability to manipulation, radicalization, and cultural fragmentation. In China, this creates stability but at the expense of pluralism and dissent; in the U.S., it fosters vibrant debate but also deep division. In short, China’s model shields, America’s exposes and each carries trade-offs in terms of resilience, creativity, and cohesion.

When connected to future competitiveness, the contrast in how Chinese and American youth experience digital culture becomes especially significant. In China, the curated online environment emphasizes discipline, technical mastery, and alignment with national priorities, which may give the country an edge in mobilizing talent for strategic industries like AI, renewable energy, and biotechnology. By encouraging young people to see themselves as contributors to collective progress and framing technological advancement as a patriotic mission, China creates a steady pipeline of engineers, scientists, and innovators who are not only technically capable but also socially aligned with state objectives. This coherence reduces the drag of cultural fragmentation and allows the state to direct youthful energy toward long-term strategic goals with relative stability.

In the United States, the openness of the digital landscape provides unparalleled freedom for creativity, pluralism, and disruptive innovation. Young people are exposed to a wide spectrum of perspectives and identities, which fuels artistic expression, entrepreneurial experimentation, and critical questioning of authority. This environment has historically produced transformative breakthroughs in digital platforms, consumer technology, and cultural industries. Yet the same forces that enable creativity also generate fragmentation, polarization, and disinformation. Instead of channeling youthful energy into a coherent national mission, the U.S. risks dissipating it into ideological echo chambers, culture wars, and identity battles that sap collective focus on long-term challenges like climate change, technological governance, and social stability.

Thus, the trade-off is unmistakable: China’s model equips it with the ability to mount large-scale, coordinated responses to future challenges, while America’s model preserves a culture of radical innovation, critical dissent, and entrepreneurial risk-taking, but also risks self-paralysis when systemic threats require unity and sustained mobilization. The central question for the decades ahead is whether the United States can retain its creative dynamism while finding institutional mechanisms to temper fragmentation and political gridlock, and whether China can sustain its stability and coherence as it grapples with demographic decline, slowing growth, and an increasingly combative strategic rivalry with the United States. In both cases, the durability of each system will hinge not on ideology, but on its capacity to adapt its strengths while mitigating its inherent weaknesses in a rapidly changing world.

Understanding the Philosophical Roots of Chinese Political Traditions

For Western readers, it is important to recognize how China’s long history shapes contemporary attitudes toward governance and authority. Unlike the United States, where political and social traditions are deeply rooted in individualism, legalism, and Christian notions of equality before God, China’s culture has been profoundly influenced by the collectivist and meritocratic principles of Confucianism. For more than two millennia, Confucian thought has functioned as the ethical and philosophical foundation of Chinese governance, embedding values of social harmony, deference to authority, and the cultivation of a virtuous, well-educated elite.

At the center of this worldview is the belief that society thrives not through unfettered individual freedom, but through a carefully ordered hierarchy, in which every person occupies defined roles and responsibilities that contribute to the well-being of the whole. The legitimacy of government, in this tradition, flows from the competence and moral integrity of those at the top, who are expected to act as custodians of collective stability. This legacy explains why many Chinese citizens view strong state authority not as an imposition on liberty, but as a guarantor of order and prosperity, a perspective very different from the suspicion of centralized power common in American political culture.

Confucianism has functioned as the moral base for Chinese society and governance, though it differs in important ways from the explicitly religious traditions that shaped the West. Unlike Christianity, which is centered on faith in God, salvation, and divine authority, Confucianism is not a religion in the Western sense. It is best understood as a philosophical and ethical system that provides moral guidance, social norms, and principles for good governance. While Confucian rituals and ancestral veneration carry a spiritual dimension, the focus is not on worshiping a deity but on cultivating virtue, fulfilling duties within the social order, and achieving harmony between individuals, families, and the state.

Confucianism’s influence has been profound because it provided a code of ethics rather than a doctrine of faith. It emphasized education, meritocracy, and moral responsibility as prerequisites for leadership, shaping institutions like the imperial examination system and informing contemporary political culture. At its core lies the conviction that society flourishes when individuals perform their roles within a hierarchy, whether as ruler and subject, parent and child, or teacher and student with respect, duty, and virtue guiding each relationship. This framework created a collectivist orientation that prioritizes harmony and stability over individual autonomy, a sharp contrast to the West’s legalistic, rights-based model rooted in Christian notions of individual conscience and equality before God.

Contemporaneous with Confucianism, Daoism and Buddhism play vital complementary roles in shaping the spiritual and religious fabric of China. While Confucianism emphasized earthly duties such as education, family obligations, hierarchical roles, and moral cultivation, it largely avoided metaphysical questions about the soul, the cosmos, or the afterlife. These gaps are filled by Daoism and, later, Buddhism, which developed alongside Confucian ethics rather than replacing them.

Daoism stressed harmony with the natural world and the pursuit of balance through alignment with the Dao (the Way). It cultivated practices such as meditation, breathing techniques, traditional medicine, and ritual, offering individuals a spiritual pathway that counterbalanced Confucianism’s heavy emphasis on social responsibility and order. Where Confucianism prized structure, duty, and hierarchy as the basis for a stable society, Daoism championed flexibility, intuition, spontaneity, and retreat into nature as sources of wisdom. By elevating the natural order and inner cultivation, Daoism provided a counterweight that softened the rigidity of Confucian obligations and opened space for personal spiritual exploration.

Buddhism, introduced from India around the 1st century CE, added a distinctly religious dimension by addressing suffering, karma, and rebirth. It provided answers to existential questions that Confucianism largely avoided, while also offering rich ritual life, monasteries, and a path of personal spiritual liberation. Over centuries, Buddhism was Sinicized, blending with Confucian and Daoist values to form a uniquely Chinese religious landscape.

Together, these three traditions—often described as the “Three Teachings” (San Jiao)—shaped Chinese society in complementary ways. Confucianism anchored governance and social ethics, Daoism offered a philosophy of nature and personal cultivation, and Buddhism provided spiritual depth and a framework for transcending worldly suffering. Unlike the West, where Christianity sought to unify moral, spiritual, and institutional life under one religious framework, China historically balanced multiple traditions, with Confucianism as the moral base but Daoism and Buddhism enriching its spiritual and religious dimensions.