Throughout human history, our species has sought not only to survive, but to profoundly reshape the world in pursuit of our visions, aspirations, and ambitions. This impulse has produced staggering achievements from magnificent civilizations, technological miracles to artistic triumph, but it has also triggered unintended consequences, profound disruptions, and systemic crises. At the heart of these crises lies a persistent, deeply rooted internal challenge: humanity’s historic inability to fully understand and effectively integrate into the complex worlds it occupies and shapes.

This dilemma emerges across three distinct yet deeply interconnected realms: the natural world from which humanity arose, the built world we created to house our societies and cultures, and now the digital, quantum, and AI-driven world—possibly our final frontier of creation. Our ongoing failure to achieve harmony with our surroundings and our own creations, both natural and artificial, represents perhaps the defining crisis of our time.

Humanity occupies not one, but three interwoven worlds, each with its own logic, demands, and dynamics:

- The Natural World: the living, breathing ecosystems within which we evolved and upon which we fundamentally depend;

- The Built World: our constructed environments, the cities, infrastructures, and habitats where we live, work, and interact;

- The Digital, Quantum, and AI World: an emergent landscape defined by powerful technologies capable of reshaping the very nature of human existence, identity, and consciousness.

Each of these worlds is distinct, yet they share a crucial commonality: humanity’s persistent struggle to harmoniously integrate with them. Our record of interaction with these spheres reveals not only our genius and adaptability but also our enduring short-sightedness and naiveté. The stakes could hardly be higher. Our capacity to successfully integrate with the worlds we inhabit and create, will determine the quality, meaning and ultimate destiny of human life.

Why have we so profoundly failed to integrate ourselves into the natural and built environments that both sustain and reflect us? Why do our cultural institutions—those meant to orient, educate, and govern—seem increasingly incapable of managing the complexity we ourselves have generated? And why, amid astonishing technological progress, are we losing the ability to even understand, let alone guide, the systems we’ve brought into being?

These questions cut to the core of humanity’s present crisis. From the accelerating degradation of ecosystems to the psychological dislocation of urban life, from the chaos of a destabilizing climate to the fragmentation of our digital realities, the signs of unraveling are unmistakable. Yet beneath these surface symptoms lies a more profound and often overlooked failure: the steady erosion of our ability to think, act, and design in ways that honor the deep interconnectedness of the systems we inhabit and influence.

Modern institutions, whether political, educational, economic, or technological, were forged in an era that prioritized mastery, predictability, and control. They evolved under an industrial logic that reduced nature to a resource, society to a market, and knowledge to measurable data. In doing so, they inherited and amplified a mindset that prizes compartmentalization over connection, efficiency over wisdom, and progress over coherence.

Our epistemologies have likewise narrowed. We privilege what can be quantified and modeled, often at the expense of what is qualitative, contextual, and relational. As a result, we’ve built systems of staggering complexity, while allowing our understanding of them to become increasingly fragmented. We treat the natural world, the built environment, and even our technologies as externalities, as objects to be managed, rather than as entangled extensions of ourselves.

This fragmentation of knowledge has been mirrored by a fragmentation of responsibility. No single institution sees or feels accountable for the whole. Environmental degradation is treated as separate from urban design. Technological disruption is siloed from its cultural and psychological effects. In our obsession with mastery, we’ve lost the ethic of relationship.

Earlier civilizations, for all their limitations, placed human life within a meaningful cosmological order. Their governance, rituals, and built forms were attempts, however imperfect, to align with something greater than themselves. Our modern world, by contrast, lacks a coherent metaphysical narrative. Without a shared vision of where we belong in the great web of life, we float unmoored in systems we can no longer comprehend, much less steward.

History bears the imprint of this pattern. Time and again, empires that once flourished through a deep integration with their guiding myths and social bonds have unraveled when that coherence fractured. Today, as we face the simultaneous breakdown of ecological, political, and cultural systems, we must confront a sobering question: are we tracing the same arc of decline? Not because history repeats itself in exact form, but because it echoes in the recurring patterns of disconnection we have yet to fully acknowledge.

Our failure is not merely one of inadequate planning, flawed policy, or stalled innovation. It is a deeper kind of forgetting. A civilizational amnesia rooted in our loss of the wisdom and humility needed to truly belong to the worlds we now so powerfully shape.

The Natural World: A Legacy of Disconnection

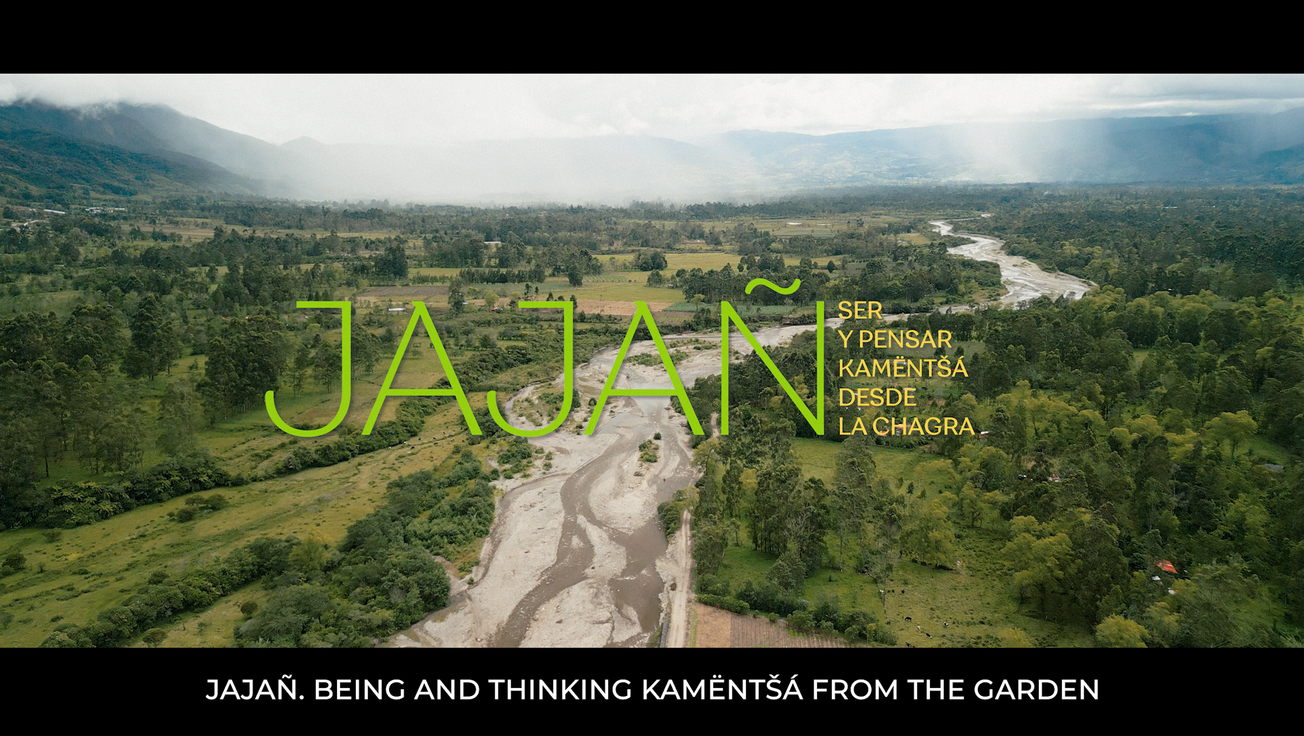

From the moment our species emerged approximately 300,000 years ago, humans existed closely attuned to nature's rhythms. These early communities typically held extensive ecological knowledge, deeply appreciated their dependence on local ecosystems, and developed cultural practices and taboos specifically aimed at sustaining ecological balance. But roughly ten thousand years ago, humanity's relationship with the natural world underwent a dramatic transformation. With the rise of agriculture, human societies began profoundly reshaping their environments. This marked a critical transition from nomadic lifestyles to permanent settlements, paving the way for widespread agricultural practices, domestication of animals, and intensive resource extraction at a scale previously unimaginable.

This pivotal transformation, arising independently across multiple regions of the world, marked the beginning of a long arc of alienation from natural systems, a trajectory that continues to shape our present. The agricultural revolution enabled unprecedented population growth and laid the foundation for the rise of cities and states. Yet it also radically altered humanity’s relationship with the environment in ways both profound and enduring.

First, agriculture introduced the concept of private land ownership and fixed territorial boundaries, replacing the more fluid, reciprocal relationship that hunter-gatherer societies had maintained with their landscapes. Second, it led to a drastic simplification of ecosystems, as biodiverse environments were cleared and converted into monocultures centered around a handful of domesticated crops. Third, it encouraged an increasingly extractive attitude toward nature, marked by the depletion of soil fertility, the erosion of natural habitats, and widespread deforestation to make way for ever-expanding fields.

In these ways, the agricultural revolution was not merely a technological or economic shift—it was the beginning of a civilizational realignment that redefined nature as something to be controlled, segmented, and consumed.

The second major rupture in humanity’s relationship with the natural world unfolded between the 16th and 19th centuries, during the Scientific and Industrial Revolutions. The Scientific Revolution ushered in a mechanistic worldview that reimagined nature as a vast, predictable machine governed by universal laws. While this perspective proved extraordinarily effective in advancing scientific knowledge and technological capability, it also encouraged a more detached and utilitarian view of the natural world. A view that prioritized control and manipulation over reverence or reciprocity.

This intellectual shift was further deepened by thinkers such as René Descartes, whose doctrine of Cartesian dualism cast a sharp division between mind and matter, subject and object. In this view, nature was stripped of intrinsic value, reduced to inert substance becoming an object to be studied, measured, and exploited, but not related to as a living, conscious presence. Over time, this paradigm helped to institutionalize a worldview in which nature became not a community to which we belong, but a resource to be mastered.

The colonial expansion of European powers, beginning in earnest in the 15th century, served to globalize and entrench the industrial paradigm of nature. As empires extended their reach across continents, they systematically displaced and eroded indigenous ecological knowledge systems that had long sustained balanced relationships with the land. This era saw the mass introduction of European species, diseases, and agricultural practices into foreign ecosystems: transformations that radically altered ecological balances and dismantled the sustainable lifeways of countless indigenous communities. The result was a wave of ecological upheaval on a scale without historical precedent.

The Industrial Revolution also provided the means to operationalize this mechanistic worldview with unprecedented intensity. The harnessing of fossil fuels, beginning with coal, then oil and natural gas freed industrial societies from many of the energetic constraints that had previously tethered human activity to natural limits. With this new energy regime came a dramatic acceleration in resource extraction, landscape transformation, and waste generation, processes that quickly outpaced nature’s capacity to regenerate and absorb. What had begun as a shift in perception became a full-scale reengineering of the planet, driven by a model of growth that increasingly severed humanity from the ecological systems on which it depends.

The industrial mindset, forged in the crucible of mechanistic science and fossil-fueled expansion, came to shape humanity’s relationship with the environment through a set of enduring principles that continue to define modern ecological dysfunction. At its core lies reductionism, the persistent tendency to break down complex natural systems into isolated parts, stripping away the intricate webs of interdependence that characterize living ecosystems. In this view, forests become timber, rivers become water supply channels, and biodiversity becomes a series of unrelated species, each valued only insofar as it serves a discrete human purpose.

Closely tied to this is commodification, the transformation of nature into standardized, tradable units valued primarily for their economic utility. Trees, minerals, water, and even genetic material are abstracted into market assets, their essential ecological functions and intrinsic worth routinely ignored or devalued. Externalization further compounds the problem, as the environmental costs of pollution, resource depletion and habitat loss are systematically excluded from economic calculus. These are framed not as integral outcomes of industrial processes, but as inconvenient side-effects to be managed, deferred, or dismissed.

Underlying all of this is a deep-seated technological optimism, our belief that human ingenuity and innovation can resolve any problem generated by industrial expansion, rendering ecological limits obsolete. This is coupled with a profound temporal myopia, a focus on short-term profits and immediate growth at the expense of long-term planetary health. The delayed, cumulative, and often irreversible consequences of environmental degradation are overlooked in favor of near-term economic advantage. Together, these principles form a powerful but deeply flawed framework that continues to drive ecological overshoot while obscuring the systemic roots of our disconnection from the natural world.

The historical arc from the intimate, cosmically rooted lifeways of hunter-gatherer societies to the profound alienation of the industrial era is not simply a story of increasing disconnection. It marks a fundamental transformation in how humans conceive of and relate to the natural world. The dominant trajectory over time has been one of escalating separation, marked by the exploitation and systematic neglect of the ecological foundations that make human life possible. Rather than deepening our belonging within the web of life, this progression has largely severed our sense of reciprocity, replacing it with control, commodification, and detachment.

The Built World: Misalignment with Human NatureThroughout antiquity, the design of cities was deeply infused with cosmological and sacred meaning. Early urban centers around the world were conceived as microcosms of the universe, their layouts carefully aligned with celestial cycles and natural forces to reflect a harmonious relationship between human society and the cosmos. One of the most striking examples is Göbekli Tepe, located in present-day Turkey. As the oldest known monumental human structure, it profoundly challenges conventional narratives of settlement and social evolution, suggesting that spiritual and symbolic order, rather than mere survival or agriculture, may have been the original impetus for complex human organization.

Built approximately 11,500 years ago, long before the rise of agriculture, Göbekli Tepe appears to have served as an early spiritual or ceremonial hub, drawing together nomadic hunter-gatherer groups for large communal gatherings. Archaeologists speculate that these ritual assemblies, rooted in shared religious or symbolic practices, may have played a pivotal role in fostering social cohesion and encouraging more permanent settlement. Rather than economic necessity alone, Göbekli Tepe suggests that spiritual and communal impulses may have been the true catalysts for humanity’s transition from a nomadic existence to settled life and the development of agriculture. This challenges long-held assumptions about the primacy of material drivers in the emergence of civilization.

The evolution of humanity’s relationship with the built environment closely mirrors our shifting connection to the natural world. In early civilizations, human settlements were deeply informed by cosmological and spiritual principles. From the ancient sites of Anatolia to the cities of the Sumerians, Egyptians, Mayans, and Chinese, urban design was often a sacred endeavor. These early cultures oriented their cities, temples, and monuments in accordance with celestial patterns, tracking the movements of the sun, moon, and stars to express a profound alignment with the cosmos.

This cosmologically rooted approach to city planning endured through the classical and medieval eras. Cities such as Beijing, redesigned under the Yuan Dynasty in 1271, and the temple-city of Angkor Wat, completed around 1150, exemplify this tradition. Both were carefully arranged to reflect astronomical events and spiritual cosmology, serving not just as centers of political power but as terrestrial mirrors of the heavens placing human life within a larger cosmic order.

A profound transformation in urban design began to take shape during the European Renaissance (14th–17th centuries), as city planning shifted increasingly toward principles of symmetry, order, and human-centric rationality. This era marked the early rise of a more secular and functional approach to the built environment. The decisive break, however, came with the Industrial Revolution in the 18th and 19th centuries, when urban planning became overwhelmingly dictated by the demands of economic efficiency, industrial output and transportation logistics displacing the spiritual and cosmological foundations that once guided city form and human connection.

Cities such as Manchester, London, and New York came to embody this new paradigm. Their expansion and layout were no longer conceived in relation to celestial rhythms or sacred geometry, but were instead driven by the logic of the machine: factories, railroads, and commerce determined urban structure. This disconnection grew stark during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, when industrial cities like Manchester and Detroit became synonymous with overcrowding, environmental degradation, and public health crises. Industrial cities became spaces where social cohesion was eroded by pollution, squalor, and the commodification of land.

Even modernist efforts to reimagine the city fell into similar traps. Brasília, designed by Oscar Niemeyer as a utopian capital, emphasized abstract aesthetics and monumental scale over the lived needs of its inhabitants, resulting in a city admired from above but alienating on the ground. In New York, Robert Moses's infrastructure-driven vision prioritized highways and automobile access at the expense of community integrity, displacing vibrant neighborhoods and severing vital social connections in the name of rational efficiency.

Today, this legacy persists in the form of suburban sprawl, car-dependent infrastructure, and architectural forms that isolate rather than connect. These environments contribute to rising mental health issues, chronic loneliness, and fragmented communities. Despite growing evidence of the psychological toll inflicted by poorly designed spaces, urban planning continues to prioritize short-term economic gains and technical optimization over holistic, human-centered design. This reflects yet another enduring philosophical blind spot: our failure to recognize and integrate human psychological, spiritual and social needs into the environments we build lies at the root of a persistent and deepening social crisis.

The Digital, Quantum, and AI World: Humanity’s Newest Integration ChallengeAs if the challenges of integrating with the natural and built environments were not formidable enough, humanity now faces the rapid emergence of a third, equally important and complex realm: the digital, quantum, and artificial intelligence frontier. The pace and magnitude of transformation in this domain are without historical precedent. Digital networks now form the nervous system of global commerce, culture, and human interaction. Artificial intelligence is not merely reshaping industries. It is about to alter the very foundations of governance, labor, and even human identity. Meanwhile, quantum computing, still in its infancy, promises to revolutionize computation, security, and scientific understanding, potentially forcing a radical reevaluation of our assumptions about consciousness, reality, and existence itself.

And yet, once more, we appear poised to repeat the failures of the past. These technological breakthroughs are advancing largely in the absence of deep philosophical inquiry, ethical oversight, or integrated societal planning. AI systems already replicate and amplify systemic biases, manipulate public discourse, and threaten the integrity of democratic institutions. Quantum computing may unlock unprecedented power, but it also raises unsettling questions about determinism, free will, and the very fabric of what it means to be human.

The stakes could not be more profound. If left ungoverned, these technologies risk not only deepening inequality and eroding privacy, they could destabilize political systems, fragment cultural cohesion, and pose existential threats to civilization itself. Our greatest challenge is not merely the technical pursuit of Artificial General Intelligence, but the deeper task of reimagining our relationship to the systems we create. Without this shift in perspective, we risk constructing yet another world unbelievably powerful, expansive, and potentially uninhabitable—one we do not truly understand and are ill-prepared to navigate.

Three Worlds, One Integration ImperativeThe historical pattern is unmistakable. Across the natural, built, and now rapidly emerging digital and quantum realms, humanity has consistently faltered in its efforts at integration favoring fragmented solutions, short-term gains, and compartmentalized thinking over holistic understanding and long-term harmony. These failures are not isolated missteps; they reveal a deeply ingrained modernist mindset rooted in reductionism, linear logic, instrumental reasoning, and a chronic disregard for the broader systems in which we operate.

In this critical historical moment, we are called to undertake a radical reassessment. We must confront the uncomfortable truth that the so-called ‘enlightened’ mindset, which has driven centuries of progress, has also repeatedly proven inadequate in addressing the complex, interwoven challenges we now face. The question is not only ‘what’ we are building, but ‘how’ we are thinking. What philosophical reorientation might enable true integration across the worlds we inhabit and create?

What we need now is not merely innovation, but transformation, a fundamental reorientation. Only through such a shift can we begin to meaningfully reweave the human presence into the natural, built, and digital worlds in ways that are coherent, meaningful, and sustainable. The emergence of a new order rarely comes through rupture alone. Instead, it unfolds through the gradual erosion of legitimacy, the collapse of institutional trust, and the fading of once-powerful narratives. Collapse destabilizes the familiar and opens up intellectual and political space for new visions to emerge. In these liminal moments, marginalized ideas gain traction, often championed by those outside traditional centers of power. Technological disruption, ecological upheaval, and generational change become catalysts, compelling societies to adapt, rethink, and reimagine.

New paradigms are not born solely from the failure of the old, but from the urgency of new realities. They arise through synthesis that integrate fragments of the past with nascent possibilities. They are shaped by those courageous enough to chart an untried course. The decline of one order, then, is not an end, it is a threshold. It invites us to reconstruct meaning, purpose, and structure in ways that resonate with the demands of a new epoch. Whether we accept this invitation with wisdom, humility, and vision may determine our fate.