In the sweltering summer of 2025, as record-breaking heat waves scorch the globe and climate scientists issue increasingly urgent warnings, a peculiar pattern emerges in the resistance to environmental action. It is not merely economic interests or political ideology that drives climate denial and environmental destruction. It is something far more primal and psychologically complex: the crisis of modern masculinity itself.

This toxic intersection has reached its most visible manifestation with the Trump Administration, where the President serves as both symbol and catalyst of a particular brand of masculinity that views environmental protection as an existential threat to male identity. Understanding this connection is crucial because it reveals that environmental destruction is not merely a policy problem requiring technical solutions, but a deeply gendered issue rooted in how societies construct and perform masculinity.

The Psychology of Masculine Environmental Resistance

The connection between masculinity and environmental attitudes operates through what scientists have identified as the "green-feminine stereotype," a deeply ingrained cultural association that links environmental concern with femininity and positions it as threatening to masculine identity. Research conducted by Aaron R. Brough and James E.B. Wilkie, involving over 2,000 participants across American and Chinese populations, revealed the stark reality of this psychological barrier.

In their groundbreaking study, researchers found that both men and women consistently perceived eco-friendly products, behaviors, and individuals as more feminine than their less sustainable counterparts. A man carrying a reusable canvas bag at the grocery store, for instance, was seen as more feminine than one using plastic bags, regardless of his actual gender.

Perhaps most striking was an experimental finding: when men were subtly exposed to feminine imagery, such as pink floral gift cards, their sense of masculinity was threatened, prompting them to make markedly less environmentally friendly choices. In short, environmental harm can occur not out of animosity toward nature, but as a reflexive rejection of perceived femininity. As the researchers concluded, “emasculated men try to reassert their masculinity through non-environmentally-friendly choices,” revealing a direct and troubling link between gender insecurity and ecological degradation.

The roots of this phenomenon lie in the environmental movement’s historic alignment with values of care, nurturing, and protection, qualities long coded as feminine within patriarchal societies. For men whose identity depends on distancing themselves from anything associated with femininity, this association creates a psychological barrier to engaging with sustainability. Environmental disregard thus becomes a form of compensatory masculinity, a symbolic assertion of dominance not only over nature, but over the very traits society deems unmanly. In this light, gender norms don’t merely shape consumer behavior; they shape the climate crisis itself.

Trump as the Archetypal Hypermasculine Environmental Destroyer

Donald Trump offers perhaps the most conspicuous illustration of how hypermasculinity fuels environmental destruction. His presidency stands as a vivid, real-time case study in how performative masculinity, rooted in dominance, control, and rejection of vulnerability, can directly shape environmental policy. It exposes the deep and often overlooked connection between gender insecurity and ecological harm.

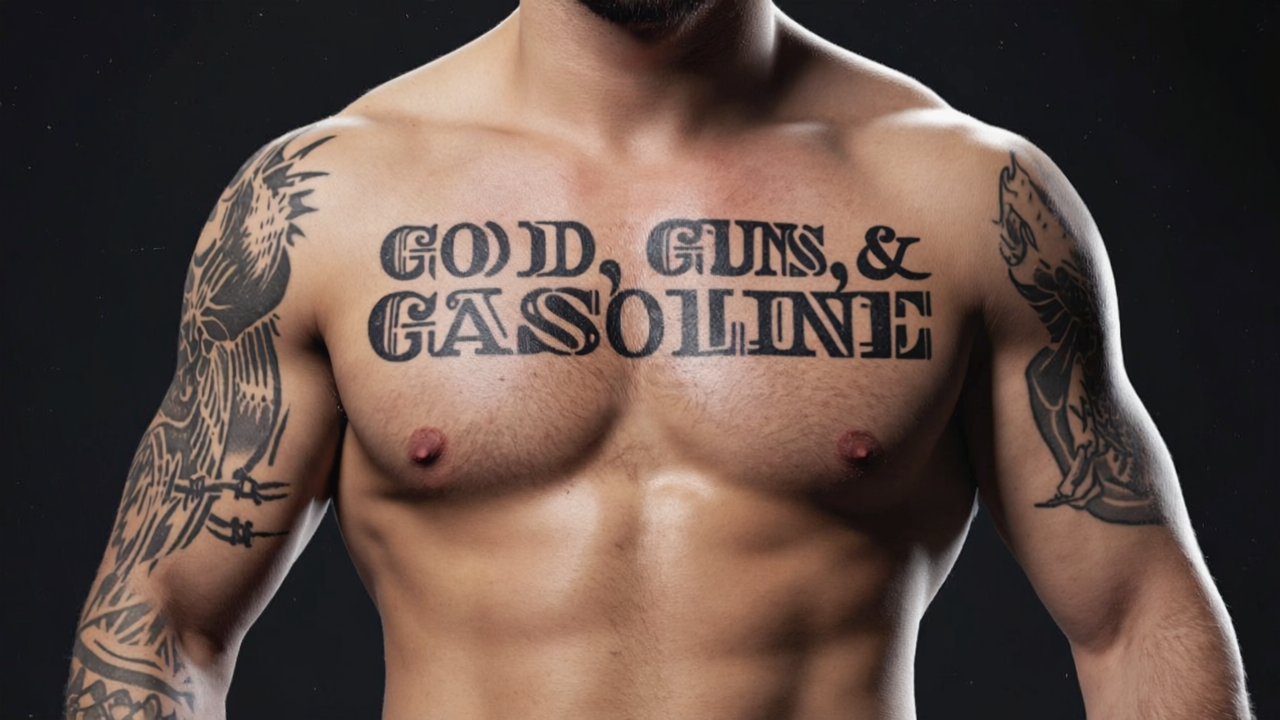

Trump’s environmental agenda was never simply about economic pragmatism; it was a theatrical assertion of power. His policies consistently favored spectacle over substance, driven less by data or sustainability than by a desire to project toughness and resist perceived weakness. Scholar Cara Daggett’s concept of petro-masculinity, the fusion of fossil fuel politics with hypermasculine identity, captures this dynamic with striking clarity. Trump’s “Make America Great Again” slogan evoked a romanticized vision of post-war suburban life: patriarchal families, cheap gasoline, sprawling highways, and industrial dominance. In this worldview, climate action and gender equality were not policy challenges, they were threats to a nostalgic, fossil-fueled vision of masculine order.

Under Trump, environmental deregulation becomes a cultural weapon, wielded not just to benefit industry, but to reaffirm a gendered identity rooted in control over nature and resistance to change. His legacy underscores a sobering truth: environmental degradation is not only a matter of policy failure. It is also, at times, a manifestation of cultural and psychological insecurity.

The scale of Donald Trump’s environmental rollback is without precedent. During his first term, his administration dismantled more than 100 environmental regulations, and in his second term, the Environmental Protection Agency itself described one initiative as “the biggest deregulatory action in U.S. history.” But these actions were not merely framed as economic necessity, they are cast as performances of masculine defiance, deliberately positioned in opposition to what was characterized as the “feminine” values of caution, care, and environmental responsibility.

This posture was mirrored in Trump’s broader leadership style, most notably during the COVID-19 pandemic. His refusal to wear a mask was not just a dismissal of public health guidance, it was a rejection of the idea that vulnerability and protection are compatible with strength. Rather than framing mask-wearing as an act of courage or communal responsibility, he portrayed it as a sign of weakness. Conservative commentator Tomi Lahren made this gender coding explicit when she mocked Joe Biden for wearing a mask, quipping that he "might as well carry a purse."

This same pattern of equating protective behaviors with femininity and treating them as threats to masculine identity is central to Trump’s environmental stance. In his worldview, regulation became emasculation, and safeguarding the environment was recast as a symbol of softness or surrender. His administration's policies reveal a troubling cultural narrative: that to dominate the earth, like to dominate the body politic, is to prove one's manhood regardless of the long-term consequences.

Trump’s economic messaging is steeped in the same gendered logic that shapes his environmental agenda. His pledge to “get your husbands back to work” did more than signal support for economic recovery, it explicitly tied masculine identity to fossil fuel-reliant industries. By centering his rhetoric around traditionally male-dominated sectors such as manufacturing, mining, and construction while largely ignoring the equally vital, female-dominated fields of care work, he reinforced a cultural association between manhood and the exploitation of natural resources.

His public performance underscores this narrative. Donning hard hats, climbing into the cabs of semi-trucks, and positioning himself amid heavy industrial equipment, Trump enacts a symbolic dominance over machinery and, by extension, the natural world. These photo ops are not incidental; they were expressions of a worldview in which masculinity is affirmed through control, extraction, and force.

More revealing still is how Trump’s brand of hypermasculinity thrives on the creation of enemies. As historian Kristin Kobes Du Mez observed, “militancy is at the heart of his identity, and militancy requires enemies.” Under this framework, environmental scientists, climate activists, and international climate accords are not merely policy opponents, they were perceived threats to the masculine order. Their advocacy for restraint, cooperation, and ecological responsibility undermines the narrative of unchallenged dominance that Trump projects. In his world, to protect the planet is not only to protect the weak, it was to be weak. And so, environmentalism itself became a battlefield in a larger cultural war waged to preserve the illusion of unyielding masculine control.

The Roots of American Male Insecurity

The hypermasculine backlash against environmental action cannot be fully understood without recognizing the deeper crisis of male identity unfolding in contemporary America. At the heart of this crisis lies a profound economic transformation. The nation’s shift from a manufacturing-based economy to one centered on services and knowledge over the last 50 years has steadily eroded the traditional pillars of masculine identity: those rooted in physical labor, industrial strength, and the role of the breadwinner.

Despite these changes, a striking 86% of men still define manhood primarily through the lens of being a “provider,” according to recent studies. Yet the economic foundation for fulfilling that role has been steadily dismantled. As traditional blue-collar jobs disappear or decline in status, many men experience a sense of dislocation, disempowerment, and loss of purpose. Within this context, environmental regulations that threaten fossil fuel or industrial employment are not simply policy disputes, they become symbolic affronts to an already imperiled masculine identity.

The fossil fuel industry has adeptly seized on this cultural vulnerability, framing environmental protection not as a moral imperative or economic transition, but as a direct assault on working-class manhood. By casting green policies as elitist, effeminate, or anti-labor, the industry has positioned itself as a defender of masculine pride and economic dignity. In so doing, it has turned climate policy into a cultural battleground, where identity eclipses evidence, shaped in no small part by the evolving landscape of gender roles. As women have achieved greater economic independence and social parity, the traditional male roles of protector and provider have diminished in centrality, unsettling long-held conceptions of masculinity. For many men, this shift generates a deep sense of insecurity, and environmentalism, with its ethos of care, cooperation, and long-term responsibility, can feel like a further erosion of masculine authority. In this view, concern for the planet is not just unmanly—it is subversive.

The rise of social media and digital culture has only intensified these anxieties. Online echo chambers routinely frame environmental concern as a form of feminine weakness, while glorifying hypermasculine posturing as strength. Within these curated spaces, performative toughness is rewarded with social validation, and empathy or restraint is mocked as weakness.

The psychological toll is evident. Researchers have noted a growing crisis of self-esteem among young men, many of whom find themselves adrift in a world where traditional masculine roles no longer offer the clarity or security they once did. This vulnerability creates fertile ground for hypermasculine influencers and authoritarian political figures who offer easy answers and scapegoats, chief among them, environmental protections. In their rhetoric, restoring male power becomes inseparable from rejecting ecological responsibility, turning climate denial into a ritual of masculine reaffirmation.

A Global Phenomenon

The connection between hypermasculinity and environmental degradation is far from a uniquely American phenomenon. It has become a global pattern, woven into the cultural, political, and media fabrics of diverse societies. Across continents, this dynamic consistently reveals itself in the ways men perceive, respond to, and often resist environmental responsibility.

A growing body of research underscores this trend. Studies conducted in Sweden, Canada, Australia, and Germany have all documented a significant gender gap in attitudes toward climate change. Men, across these contexts, are consistently more likely than women to express skepticism about human-induced global warming and to oppose environmental policies. A notable study published in Nature Climate Change found that Swedish men were not only less convinced of the scientific consensus on climate change but also less supportive of policy measures aimed at mitigation. These findings suggest that gendered responses to environmental issues are not the product of isolated cultural quirks but rather reflect a deeper, structural alignment between masculine identity and resistance to ecological concern.

Further research reveals that the perception of environmentalism as inherently feminine transcends national and cultural boundaries. In both American and Chinese studies, participants routinely associated environmentally friendly behaviors, products, and lifestyles with femininity. This “green-feminine” stereotype generates a potent psychological barrier—especially for men who strongly identify with traditional notions of masculinity. For these individuals, the act of engaging in sustainable behaviors risks being read not as virtuous, but as emasculating. The fear of appearing weak or effeminate discourages pro-environmental choices, even among those who may privately acknowledge the urgency of the climate crisis.

Taken together, these patterns reveal the emergence of a global cultural script in which ecological responsibility is not merely a matter of politics or economics, it becomes a referendum on masculinity itself. In this framework, environmental concern is often viewed as incompatible with traditional male identity, casting sustainability as a sign of softness or submission. As a result, efforts to address climate change must go beyond technological breakthroughs and policy reforms; they require a profound cultural reckoning with the gendered narratives that shape how men relate to the natural world.

The global rise of authoritarian populism has given this masculine environmental resistance a potent political form. Leaders such as Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro, Hungary’s Viktor Orbán, Russia’s Vladimir Putin, and the Philippines’ Rodrigo Duterte have fused hypermasculine performance with overt environmental destruction. These figures understand that environmental protection, with its ethos of restraint, cooperation, and interdependence, challenges the very foundation of the authoritarian masculine ideal, which thrives on dominance, sovereignty, and unilateral power.

Bolsonaro, for instance, has derided environmentalists as “obstacles to progress” and oversaw a dramatic surge in Amazon deforestation, casting ecological exploitation not as a crisis, but as an act of national pride. His aggressively macho persona—anti-intellectual, confrontational, and dismissive of climate science—mirrored the militarized nationalism through which he justified environmental degradation.

In Hungary, Viktor Orbán has explicitly linked climate action to what he pejoratively terms “gender ideology,” portraying both as threats to traditional Hungarian values imposed by foreign liberal elites. Meanwhile, Vladimir Putin has carefully cultivated an image of rugged masculinity, repeatedly posing shirtless on horseback or while hunting, reinforcing an ethos of conquest over nature. These theatrical displays are not mere vanity, they signal a worldview in which environmental regulation is interpreted as emasculation and weakness.

In each case, environmental destruction is not just collateral damage, it is part of the performance. These leaders weaponize gender anxiety to undermine ecological responsibility, turning care for the planet into a symbolic battleground where masculinity is affirmed through dominance rather than stewardship. Understanding this interplay is crucial, for until the cultural underpinnings of masculine identity are reimagined, the political resistance to climate action will remain deeply entrenched and dangerously global.

This dynamic is evident even within democratic societies. In Australia, former Prime Minister Scott Morrison dramatically brandished a lump of coal in Parliament, extolling its role in the national economy while dismissing climate concerns as irrational and overblown. His gesture was more than a defense of energy policy, it was an act of cultural signaling. By aligning himself with coal, Morrison reinforced a vision of national strength and masculine identity rooted in extraction, industrial dominance, and resistance to perceived weakness.

Taken together, these examples underscore that the entanglement of masculinity, nationalism, and environmental resistance is not confined by geography or regime type. It is a global phenomenon. Whether expressed through overt climate denial or through the more subtle coding of ecological concern as unmanly, these cultural currents profoundly shape public perception and policy response.

As such, the struggle to confront climate change cannot be separated from the crisis of masculine identity. Technological innovation and economic reform, though essential, are not enough. A truly effective global climate strategy must also reckon with the deeper cultural narratives, those that equate domination with strength, care with weakness, and environmental protection with emasculation. Only by transforming these stories can we hope to build a future where ecological responsibility is embraced as a universal, rather than a gendered imperative.

The Path Forward

Confronting the intertwined crises of climate change and masculine identity requires far more than legislative reform. At the heart of this shift must be the emergence of broader, more inclusive models of masculinity, models that recognize care, cooperation, and environmental stewardship not as vulnerabilities, but as powerful expressions of strength. Hopefully masculinity can be reimagined, not as a force of domination and control, but as a commitment to responsibility, interdependence, and the safeguarding of life. In doing so, we can cultivate a vision of manhood that serves not only the individual, but the planet and generations yet to come.

One inspiring model is the Rwanda Men's Resource Centre (RWAMREC), which has pioneered programs that encourage men to adopt caregiving roles within their families and communities. These initiatives have led to measurable declines in domestic violence, improved maternal and child health outcomes, and strengthened social cohesion. The ripple effects of such programs go beyond family well-being. They cultivate the empathy, collaboration, and civic engagement essential for tackling collective challenges like environmental degradation. When men are empowered to nurture rather than dominate, they become allies in the work of building sustainable, equitable societies.

Economic policy must also address the structural roots of masculine insecurity, particularly the erosion of traditional working-class roles in a rapidly changing economy. For too long, the clean energy transition has been framed in ways that inadvertently alienate men whose identities are tied to industries like fossil fuels, manufacturing, or construction. This need not be the case. A green economy, if designed with intention, can offer a new narrative of masculine purpose.

Governments must invest in well-paying, dignity-affirming jobs in renewable energy, ecological restoration, sustainable transportation, and climate-resilient infrastructure. These sectors can become avenues through which men reclaim a sense of pride and provision, not by exploiting nature, but by healing and protecting it. Programs like ‘Solar on the Roof’ in the United States or Germany’s vocational training for energy retrofitting demonstrate how workforce development can be both climate-aligned and identity-affirming. When men see themselves not as victims of change but as architects of a sustainable future, climate solutions gain powerful new allies.

Educational reform also plays a crucial role. Curricula that integrate emotional intelligence, ecological literacy, and gender equity from an early age can help dismantle the binary thinking that casts care as feminine and strength as masculine. Media, art, and storytelling must likewise elevate alternative masculine archetypes, fathers who nurture, workers who restore ecosystems, leaders who lead with humility.

The path forward is not about feminizing men or erasing gender. It is about liberating all of us from narrow definitions that pit identity against survival. Climate action must be reframed not as sacrifice, but as service. Environmental responsibility must be understood not as surrender, but as stewardship. And masculinity itself must be reclaimed not as a tool of domination, but as a force for regeneration, protection, and collective renewal.

In a world increasingly shaped by ecological limits and shared vulnerability, the most courageous act may be not to conquer—but to care.

The relationship between hypermasculinity and environmental destruction represents one of the most urgent yet under addressed challenges of our time. The Trump Administration's environmental assault is not an aberration but a logical culmination of toxic masculine dynamics that operate throughout society. His success in mobilizing masculine insecurity against environmental protection reveals both the depth of this problem and the political power it can generate.

The choice before us is clear: we can continue to allow masculine insecurity to drive environmental destruction, or we can work to transform society’s framing of masculinity itself. This transformation is not about eliminating masculine identity but about expanding it to include the qualities necessary for planetary survival. The same masculine energy that has driven environmental destruction can be redirected toward environmental protection. The same desire for strength and significance that fuels hypermasculine posturing can be channeled into building a sustainable future. The transformation of masculinity is not a luxury we can postpone, it is an essential component of solving the environmental crisis.