The promise carries a seductive simplicity, almost too good to be true: plant a tree, save the planet. In corporate boardrooms around the world, executives embrace carbon offset programs with the reassuring logic of basic arithmetic. One ton of carbon released here, one ton supposedly absorbed there through carefully orchestrated tree-planting initiatives. The numbers seem to add up, consciences are soothed, and business proceeds uninterrupted. Yet emerging research paints a far more troubling picture, one that dismantles this comforting narrative and reveals the perilous oversimplification underlying much of our climate strategy.

A groundbreaking report released by the United Nations University in May 2025 issues a sobering warning to those who view tree planting as a straightforward remedy for the climate crisis. Far from being an environmental cure-all, the research reveals that tree planting can actually lead to an increase in greenhouse gas emissions. This counterintuitive insight underscores a deeper and more unsettling truth: the path to climate stability is far more intricate than our preferred narratives suggest. In our eagerness for easy solutions, we may be inadvertently advancing strategies that compromise the very objectives we claim to pursue.

The wildfire paradox stands as one of the most striking illustrations of how well-meaning climate interventions can disastrously backfire. Between 1911 and 2011, forest density in the western United States increased nearly sevenfold, transforming vast landscapes into what scientists now describe as a tinderbox. These denser forests, whether planted or naturally regenerated in the pursuit of carbon sequestration, have become potent fuel for increasingly ferocious wildfires that release staggering amounts of stored carbon back into the atmosphere. The irony is both cruel and unmistakable: trees intended to capture carbon dioxide ultimately amplify its release when they succumb to the very infernos their proliferation helped to intensify.

The wildfire paradox reaches far beyond the realm of carbon accounting, extending into the delicate balance of water resources and drought resilience. As the UN report observes, more trees mean more roots drawing from already strained water supplies, intensifying the very drought conditions that render forests more vulnerable to catastrophic fires. This dynamic reveals a deeper truth about ecological systems: they are profoundly interconnected. Actions taken with the best of intentions in one domain can trigger cascading consequences across another, often undermining the very goals they were meant to achieve.

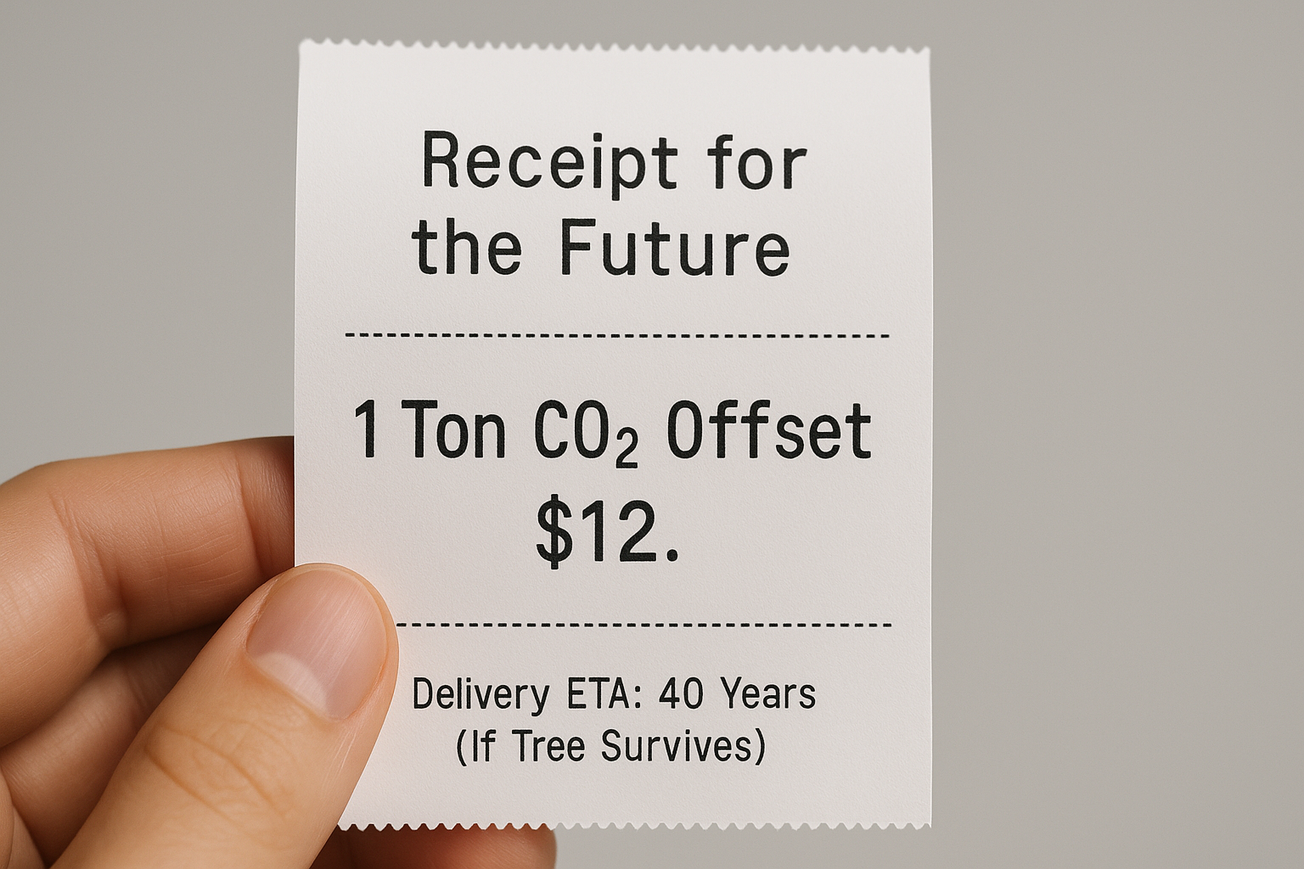

The temporal dimension of tree planting introduces a profound complexity that carbon offset markets routinely overlook. Corporations may purchase carbon credits and claim instant carbon neutrality, yet the trees funded by these offsets will take decades to mature and sequester meaningful amounts of carbon, if they survive at all. This creates what researchers have termed “the illusion of immediate impact,” allowing high-emission business models to persist under the guise of future carbon removal. The time lag between emission and sequestration is not a trivial detail; it means that greenhouse gases continue to accumulate in the atmosphere precisely when swift and substantial reductions are most critical to averting catastrophic climate tipping points.

Recent research from the University of California, Riverside, adds yet another layer of complexity to our understanding of tree-planting impacts by uncovering chemical interactions often overlooked in mainstream climate models. Trees emit biogenic volatile organic compounds (BVOCs), which react with other atmospheric gases to form particles. These interactions can have dual and contradictory effects: on one hand, they may cool the planet by promoting cloud formation and reflecting sunlight; on the other, they can worsen air quality by increasing particulate pollution. The overall impact is highly dependent on geographic context. Tropical forests tend to offer more pronounced cooling benefits with fewer negative consequences, while forests in higher latitudes may actually exacerbate warming due to surface darkening and other feedbacks.

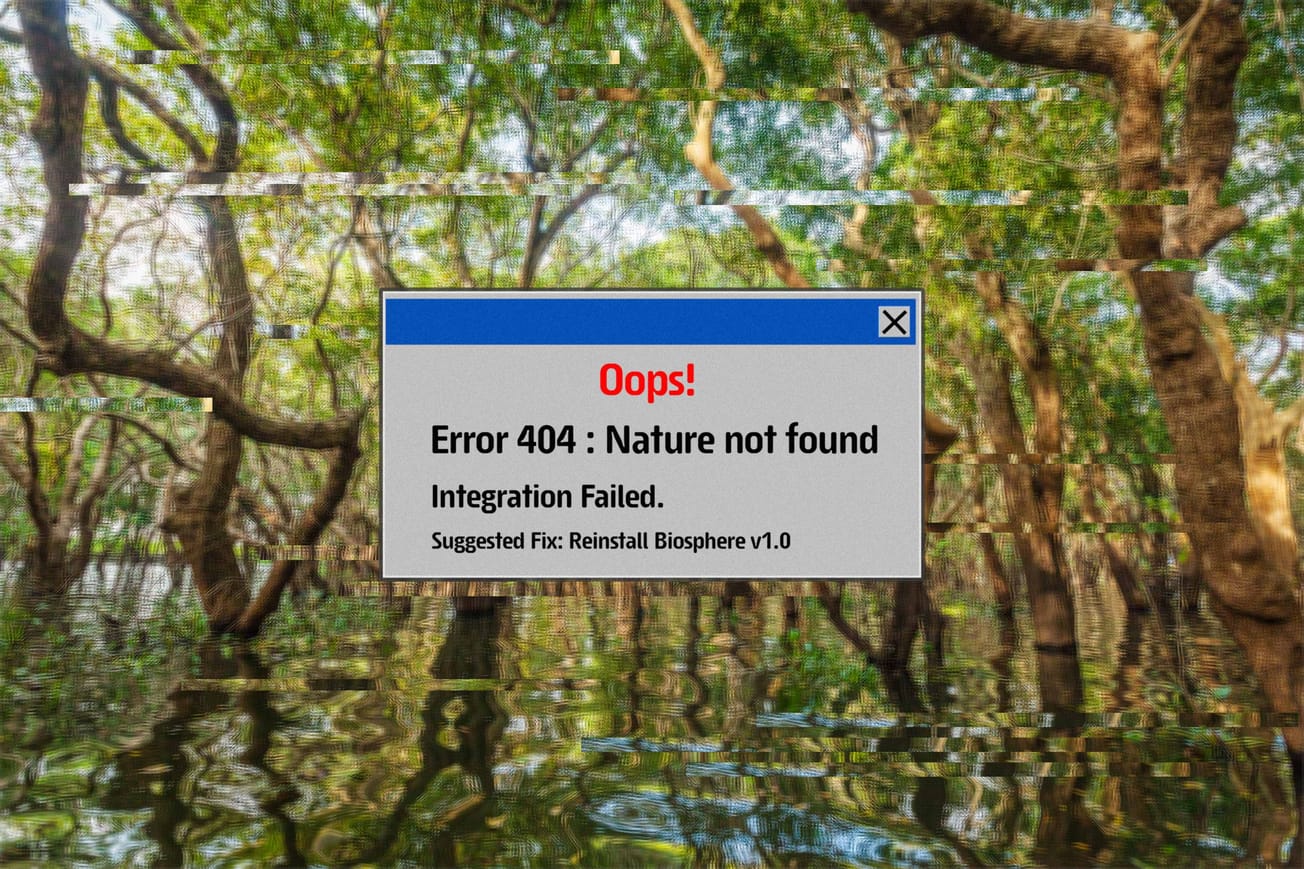

Perhaps most alarming is the systemic breakdown of carbon offset verification, as exposed by researchers from the University of New South Wales and the Australian National University. Their investigation into human-induced forest regeneration projects, spanning 42 million hectares, revealed that a staggering 95% of credited areas were located on land that had never been meaningfully cleared, effectively awarding credits for reforesting landscapes that had never lost their trees. Even more troubling, 29% of the areas had existing forest cover at the time the projects commenced. The discrepancy between reported and actual outcomes was profound: while credits were granted for achieving 30% canopy cover, the real figure averaged just 13%. As lead researcher Dr. Megan Evans noted, these are “such huge failures that it's almost beyond belief,” a damning indictment of the credibility upon which the carbon offset market rests.

The scale of this deception is breathtaking. The Australian projects alone have generated over 45 million carbon credits—valued at approximately $1 billion, accounting for nearly 30% of all credits issued under the nation’s offset scheme. Yet most of the reported increases in tree cover can be attributed to natural phenomena, such as rainfall boosts during La Niña years, rather than to any deliberate human effort. Despite this, corporations and governments continue to claim credit for these naturally occurring changes, effectively monetizing the weather.

These systemic failures confirm what many environmental experts have long warned: carbon offsetting, particularly through tree planting, has become a sophisticated form of greenwashing. It enables high-emission entities to perpetuate harmful practices while projecting an illusion of climate responsibility. The popularity of tree planting as an offset strategy lies in its seductive simplicity and emotional appeal. Who wouldn't support planting trees? The imagery of thriving forests and verdant landscapes offers a feel-good narrative—one that masks the far more complicated truths of ecosystem dynamics, carbon accounting, and climate mitigation.

Beyond the systemic failures of carbon offset schemes lies a deeper and even more unsettling truth: forest planting itself can directly increase greenhouse gas emissions, not just indirectly through wildfire risk, but through the intrinsic biological activity of the trees being planted. Groundbreaking research published in Science of The Total Environment (2024) revealed that tropical tree leaves, particularly those of pioneer species commonly used in reforestation, emit significant levels of greenhouse gases. Using portable analyzers, scientists measured emissions from these leaves and found that pioneer species release 119% more nitrous oxide (N₂O) than mature forest trees. Even more concerning, these same pioneer species act as net emitters of methane (CH₄), while established forest species serve as net methane sinks. As the study’s authors concluded, “pioneer tree species significantly contribute to net CH₄ and N₂O emissions, potentially counteracting the carbon sequestration benefits in regenerating tropical forests.”

The magnitude of these emissions becomes even more apparent when examined through long-term ecological data. A comprehensive 35-year study published in Nature Communications Earth & Environment (2025) monitored soil greenhouse gas fluxes across a range of forest management regimes, utilizing more than 14,000 manual chamber measurements. The results were sobering: pine plantations emit an average of 1.3 kilograms of nitrous oxide per hectare each year, while land converted to forestry experienced a 115% increase in soil N₂O emissions and an 84% decline in its ability to absorb methane. These changes are not environmentally trivial. They translate into a measurable warming impact driven by gases far more potent than CO₂. Indeed, nitrous oxide possesses a global warming potential 265 to 298 times greater than carbon dioxide over a 100-year period.

Together, these findings challenge the widespread assumption that forest planting offers unambiguous climate benefits. Instead, they reveal a more complex and troubling reality: newly planted forests may act as net contributors to global warming for decades, until mature forest dynamics eventually stabilize emissions. Far from serving as a quick climate fix, tree planting, especially when driven by oversimplified offset frameworks, can inadvertently undermine the very goals it aims to achieve.

The broader implications of these findings reach well beyond the shortcomings of tree planting schemes. They expose a profound flaw in our collective approach to the climate crisis: an enduring preference for simplistic fixes to extraordinarily complex challenges. Climate change is not a problem that can be patched with feel-good solutions; it demands a sweeping transformation of our energy systems, transportation networks, agricultural practices, and industrial infrastructure. It requires a reckoning with uncomfortable realities about unsustainable consumption, growth-driven economic models, and deeply entrenched social inequities.

Tree planting, by contrast, offers an alluring illusion that we can address climate change without fundamentally rethinking how we live, produce, and consume. This oversimplification is mirrored in policy frameworks that elevate carbon offsetting above direct emissions reductions, effectively enabling nations and corporations to postpone the difficult, often disruptive work of genuine decarbonization. The Paris Agreement’s endorsement of carbon markets and offset mechanisms reflects this broader bias: a tendency to favor market-based strategies that preserve existing economic and political structures while promising that technological or nature-based solutions can resolve systemic crises.

The path forward demands that we confront complexity head-on, rather than retreat into the illusion of simplicity. Meaningful climate action must recognize the intricate interdependence of ecological systems, the temporal disconnect between carbon emissions and sequestration, and the broader social and economic landscapes in which environmental strategies unfold. This requires a decisive shift in priorities: from offsetting to genuine emissions reduction, from symbolic gestures to scientifically grounded, long-term interventions. It also calls for robust, transparent monitoring of climate projects and an honest reckoning with the limits of nature-based solutions when deployed as substitutes for systemic change.

The failure of tree planting as a leading carbon offset strategy is more than a policy misstep. It is a cautionary tale about the seductive dangers of oversimplified climate solutions. These failures remind us that the climate crisis cannot be solved with feel-good fixes that offer moral reassurance while leaving the root causes untouched. If we are to avert catastrophe, we must lift our gaze, widen our lens, and embrace the complexity that real solutions demand, before it’s too late.