From the folk revival of the 1950s to the viral TikTok anthems of today, popular music has long served as both a mirror of society and a catalyst for its transformation, helping to guide America in its ongoing pursuit of “a more perfect union.” Since the end of World War II, protest songs have done more than reflect the spirit of their times; they have helped shape it. These songs have provided rallying cries for movements, solace for the marginalized, and uncompromising truths for those in power. They have carried the emotional weight of collective struggle and the enduring hope for justice. And yet, as the planet faces a growing environmental crisis, one cannot help but ask: where is the anthem for the environmental age?

The bond between music and activism is neither simple nor linear. Songs alone do not birth movements, but they give voice to collective emotion, amplify the urgency of demands, and carry the soul of resistance across generations. As Pete Seeger, architect of the folk revival, once remarked, “Songs won't save the world, but they can help make sure the world doesn't change us.”

As we reflect on this powerful tradition, one truth becomes clear: every enduring movement has found its voice in song. Yet the modern environmental movement, for all its urgency and global reach, remains curiously without an anthem. In an age defined by ecological crisis, this absence matters. Music gives emotion a vehicle, transforms data into feeling, and binds individuals into community. If we are to meet the planetary challenge ahead, we must not only speak, but sing with conviction, clarity, and collective purpose.

Allow me to take you on a journey through the protest music that has echoed across the arc of my eighty years, songs that stirred hearts, galvanized movements, and gave voice to the struggles of their time. From folk ballads to hip-hop anthems, these melodies, decade by decade, carried the weight of justice and the hope of change. And now, as the planet faces a growing crisis, I raise a call for the ‘Green Movement’ to find its song, a unifying anthem that speaks not only to the urgency of our ecological moment, but to the soul of our shared future.

The Foundation Years: 1945-1955

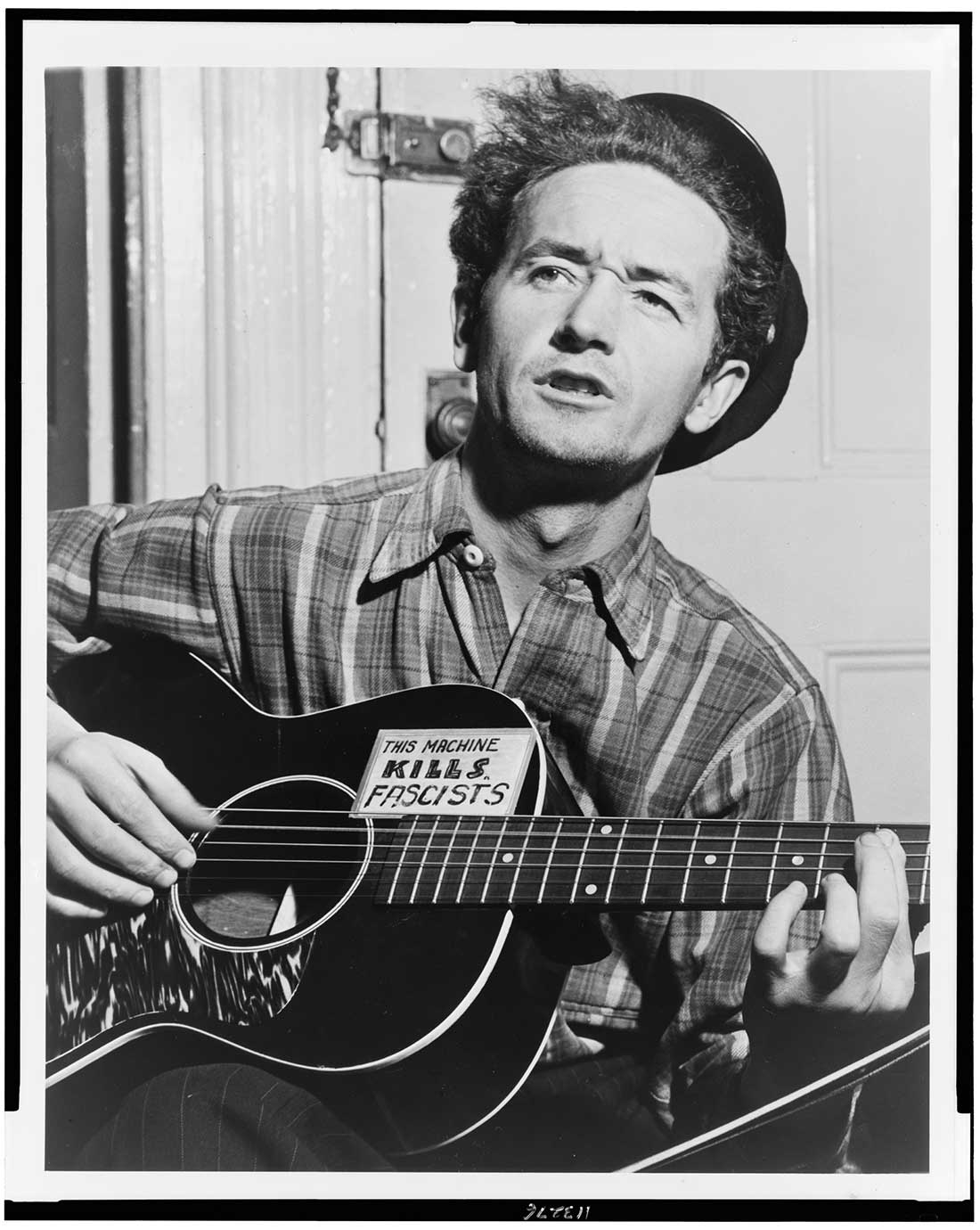

The immediate postwar era laid the foundation for modern protest music, with Woody Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land” (1940) emerging as its seminal anthem. Written as a direct retort to Irving Berlin’s “God Bless America,” Guthrie’s original lyrics included verses that sharply criticized private property and economic injustice—lines that were quietly omitted as the song was absorbed into the patriotic canon. This early act of political sanitization foreshadowed a recurring tension in the history of protest music: the uneasy dance between radical intent and mainstream co-optation.

Equally transformative was the era’s technological shift—from printed sheet music to recorded sound. The advent of wax cylinders, phonographs, and radio revolutionized the way protest songs were shared and experienced. No longer reliant on live performance alone, music could now be captured in studios and broadcast to millions. This democratization of music consumption allowed protest songs to transcend time and place, seeding the emotional and cultural infrastructure for the mass movements yet to come.

The 1950s saw the rise of Pete Seeger and The Weavers, whose music ignited the urban folk revival and laid the foundation for two decades of protest song. With their polished harmonies and accessible sound, they brought folk music to mainstream audiences—most notably with their rendition of Lead Belly’s “Good Night Irene,” which soared to the top of the charts. Yet the political climate of the Red Scare cast a long shadow. As suspicion and repression intensified, Seeger and his fellow musicians became targets. The Weavers were blacklisted, their concerts canceled, and ultimately the group disbanded. When summoned before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, Seeger refused to plead the Fifth Amendment. Instead, he invoked the First—asserting his right to speak and sing freely, setting a courageous precedent for artists confronting political persecution through the power of free expression.

The emblematic song of the era, “We Shall Overcome,” illustrates the collective spirit at the heart of protest music. Originally a gospel hymn, the song was adapted by striking textile workers, refined by Zilphia Horton at the Highlander Folk School, and later reimagined by Seeger himself, who changed “I Will Overcome” to “We Shall Overcome” and added his signature banjo rhythm. It was not the work of a single voice, but of a community shaping their shared longing into song. In time, “We Shall Overcome” would become the anthem of the civil rights movement—an enduring reminder that protest music, at its most powerful, emerges not from individual authorship, but from collective resilience and hope.

The Civil Rights Revolution: 1965

The 1965 era marked the crescendo of the civil rights movement and heralded the rise of soul music as a profound instrument of protest. At the heart of this convergence stood Sam Cooke’s “A Change Is Gonna Come” (1964), a luminous anthem that fused the raw pain of injustice with the soaring hope of transformation. It was a turning point, when popular music confronted the realities of racism not just with lyrical force, but with a depth of emotional resonance and commercial reach previously unseen.

Cooke’s song emerged from a deeply personal crucible. After being denied lodging at a Louisiana motel because of his race, and inspired by Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind,” Cooke felt an urgent need to craft a response, one that spoke directly, yet soulfully, to the lived experience of Black America. What resulted was more than a protest song; it was a spiritual declaration wrapped in velvet vocals and aching orchestration. A Change Is Gonna Come quickly transcended its moment, becoming the unofficial anthem of the civil rights movement and a prophetic refrain for future generations. With its timeless plea for dignity and justice, Cooke’s masterpiece stands as a testament to music’s power not just to reflect change, but to help summon it.

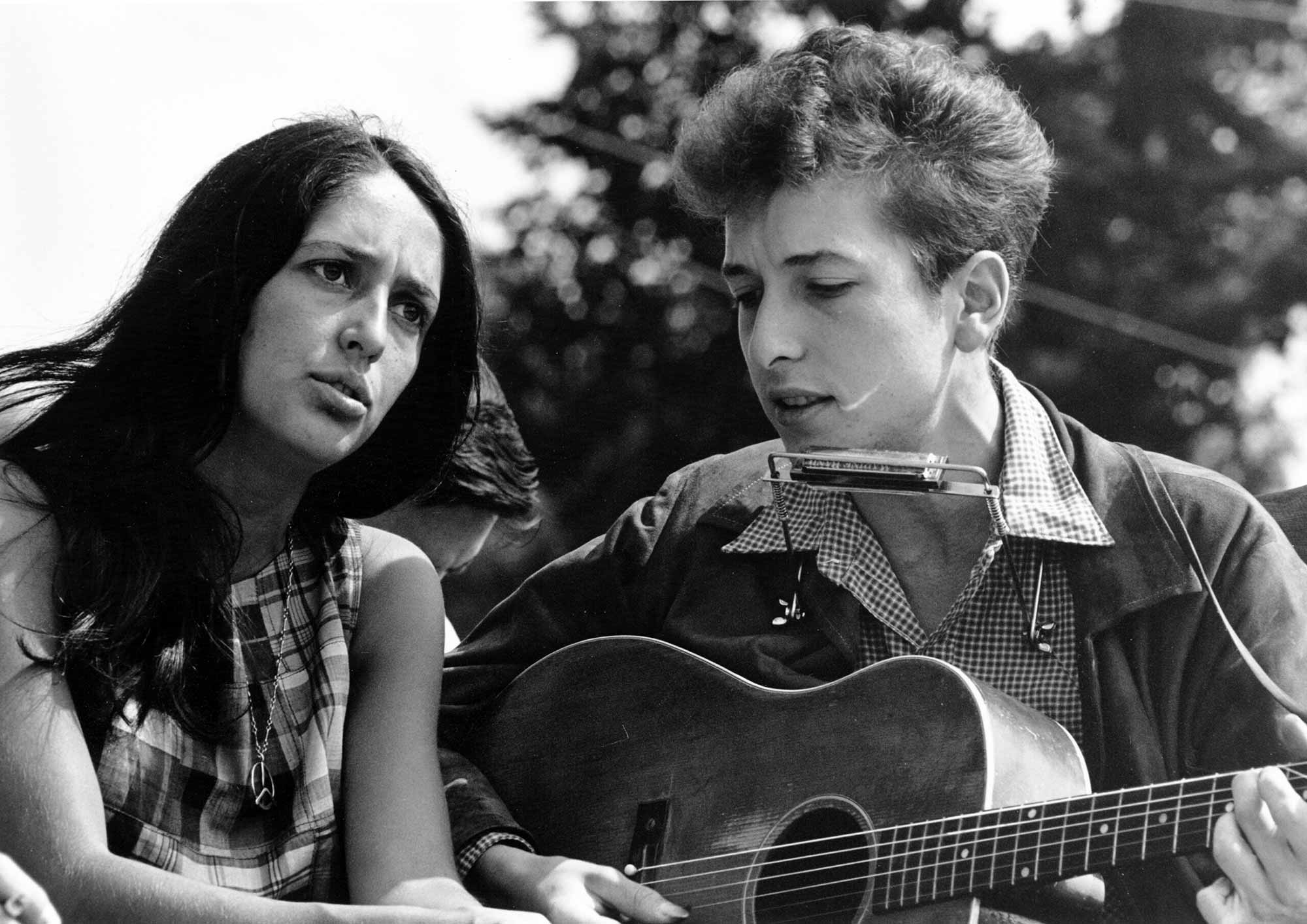

The creative exchange between white folk artists and Black soul musicians during the early 1960s gave rise to a powerful and complex dialogue within protest music. Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind” proved that a young white artist could give voice to the pain and aspirations of Black America, a gesture that resonated deeply and inspired artists like Sam Cooke to craft civil rights anthems rooted in their own lived experience. This musical cross-pollination mirrored the interracial solidarity of the civil rights movement itself, while also revealing the distinct vantage points each community brought to the shared struggle for justice. Folk music carried the raw urgency of protest into the mainstream, while soul music infused it with the weight of history, spirituality, and personal resilience.

The untimely murder of Sam Cooke in December 1964, just weeks after the release of “A Change Is Gonna Come,” cast a tragic shadow over this cultural moment and underscored the perilous intersection of race, celebrity, and activism in America. Cooke’s circle of friends, including Muhammad Ali and Jim Brown, embodied a new generation of Black public figures who refused to separate their fame from their political convictions. Together, they helped pioneer a model of artist and athlete activism that continues to shape cultural resistance movements today. Cooke’s legacy lives not only in his music but in the courage of those who still follow the path he helped illuminate.

The Anti-War Era: 1975

The Vietnam War era marked a turning point in the evolution of protest music, transforming it from a niche expression rooted in folk traditions into a powerful, mainstream cultural force. Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On” (1971) stands as a defining anthem of this period, a masterful blend of soul, sorrow, and social consciousness. Far more than a protest against war, the song captured the broader turbulence of the era: environmental destruction, urban unrest, and a nation in moral crisis. Initially dismissed by Motown founder Berry Gordy as “the worst thing I ever heard in my life,” it would go on to become one of the most revered protest songs in American history, a testament to the enduring power of art to transcend resistance and reshape public sentiment.

The anti-war movement sparked an unprecedented outpouring of protest music, with more than 700 songs across every genre grappling with the Vietnam conflict. This was the moment when rock music found its political voice, as artists like John Lennon, Creedence Clearwater Revival, and Country Joe & the Fish brought anti-war messages to massive, often youthful audiences. Their success proved that protest music could resonate commercially without sacrificing its radical core. In this era, music did more than reflect discontent. It became a soundtrack for a generation in revolt, amplifying a call for peace that reverberated from college campuses to concert halls around the world.

The generational fault lines of the Vietnam era found powerful expression in its music. This period also marked the first major wave of protest songs being censored, distorted, or co-opted by the very institutions they sought to critique. Many radio stations refused to air anti-war anthems, while others stripped songs of their political meaning and repurposed them for patriotic messaging. The tension between a song’s original intent and its public reception emerged as a defining challenge for protest musicians, a dynamic that would echo through the decades to come, as artists struggled to preserve the integrity of their message in an era of mass media and cultural commodification.

The Reagan Resistance: 1985

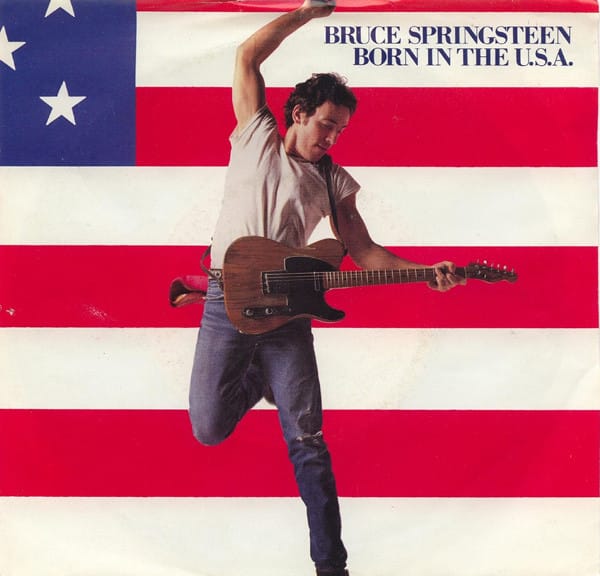

The 1980s ushered in a pivotal transformation in protest music, marked by a shift in both sound and cultural context. Bruce Springsteen’s “Born in the U.S.A.” (1984) emerged as the decade’s most iconic and perhaps most misunderstood anthem. Originally titled “Vietnam,” the song offered a blistering critique of the nation’s abandonment of Vietnam veterans and the economic hardships inflicted by Reagan-era policies. Yet its soaring chorus and martial instrumentation lent it a veneer of patriotic triumphalism, leading many, most infamously President Reagan’s reelection campaign, to mistake it for a nationalist rallying cry. It was only through public intervention by Springsteen’s team that its true meaning was reclaimed, underscoring the ongoing tension between artistic intent and public reception in the protest tradition.

Meanwhile, the decade witnessed the birth of a new protest genre, hip-hop, rooted in the lived realities of urban America. Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five’s “The Message” (1982) shattered the perception of rap as mere party music, offering instead a stark, unflinching portrait of inner-city life under Reaganomics. With its raw commentary on poverty, crime, and neglect, the song gave voice to a generation outside of mainstream political discourse. “The Message” did more than reflect the times. It catalyzed the emergence of conscious hip-hop as the dominant force in protest music for the next four decades, establishing a new language of rooted in rhythm, rhyme, and radical truth-telling.

Protest music in the Reagan era was marked by a striking diversity of genres, voices, and approaches. Punk bands like The Ramones delivered raw, unfiltered critiques of Reagan’s domestic agenda, channeling youthful disillusionment into sonic rebellion. At the same time, international artists like Nena captured the global anxiety of the Cold War with haunting anthems like “99 Luftballons,” a song that vividly imagined nuclear catastrophe triggered by a trivial misunderstanding. Together, these voices reflected a profound truth: by the 1980s, protest music was no longer confined to national borders, it had become a global language of dissent, with artists around the world responding to perceived injustice.

This decade also marked the rise of concerted efforts, both corporate and governmental, to regulate and restrain the power of protest music. The Parents Music Resource Center (PMRC) hearings in 1985, and the subsequent introduction of “Parental Advisory” labels, signaled a new phase in censorship. Disguised as a moral campaign to protect youth, these measures served to stigmatize and restrict the distribution of politically and socially charged music. The battles fought during this period would shape the terrain of artistic expression for decades to come, as protest musicians navigated an increasingly commercialized and surveilled cultural landscape.

The Hip-Hop Revolution: 1995

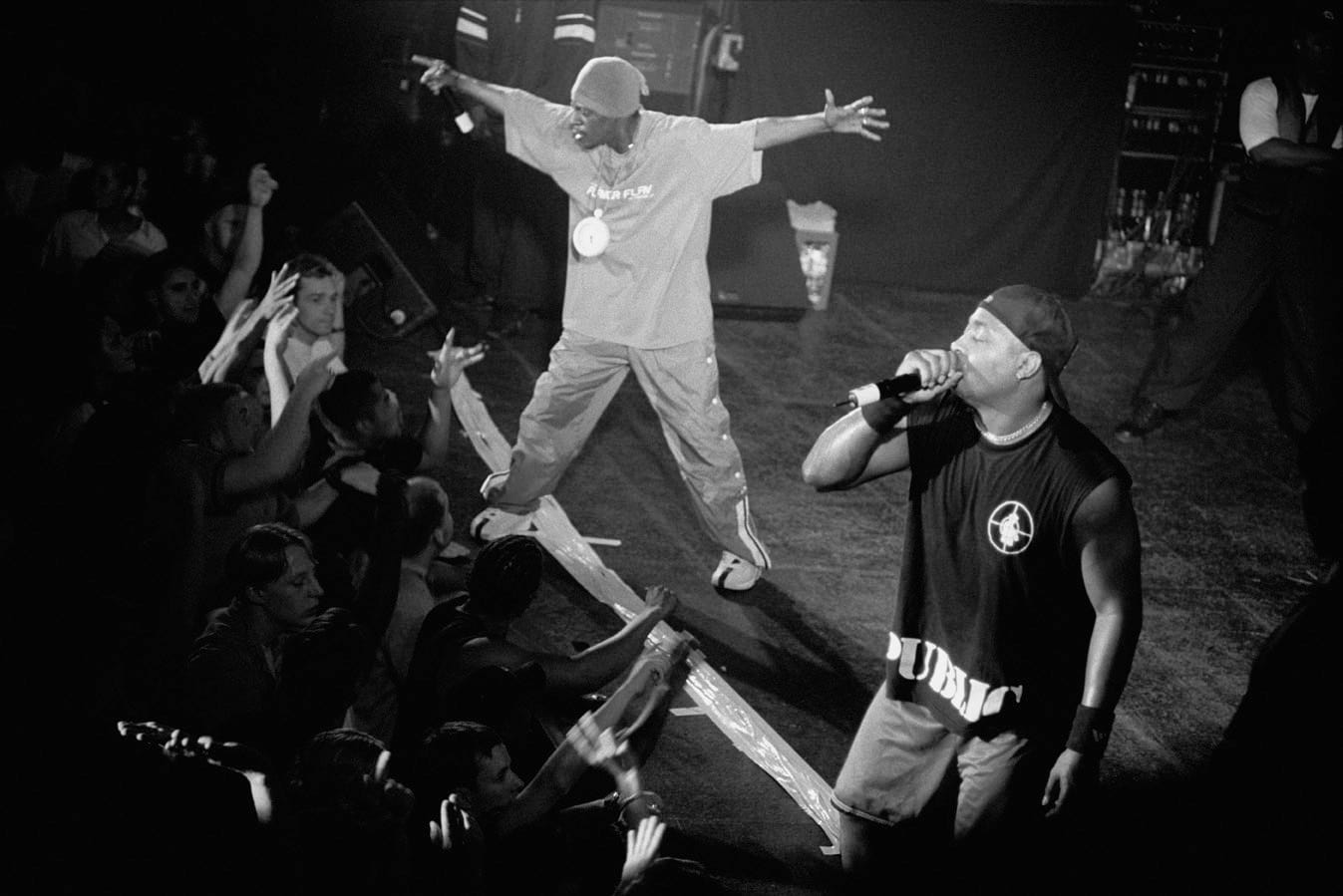

The 1990s marked another turning point in American protest music, as hip-hop emerged as its most potent and uncompromising voice. Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power” (1989) which was immortalized in Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing stands as the defining anthem of the era, a fierce and unflinching confrontation with systemic racism, police violence, and cultural erasure. Chuck D, who envisioned the song as “the hip-hop version of Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On,” succeeded in elevating rap into a fully recognized vehicle for political expression—raw, urgent, and unfiltered.

This era also heralded a profound shift in the creation and consumption of protest music. Hip-hop’s foundation in sampling enabled artists to weave the legacy of past protest movements into entirely new sonic landscapes, blending the voices of soul, funk, and jazz with modern beats and radical commentary. Its urban roots and unvarnished realism gave it a resonance and immediacy that folk and rock, by then often distanced from lived struggle, could no longer claim. In the hands of a new generation, protest music became a living archive of resilience and defiance, spoken from the streets, for the streets, and heard around the world.

The commercial rise of politically conscious hip-hop in the 1990s revealed a powerful truth: audiences were not only receptive to, but hungry for music that spoke to real-world struggles. Groups like N.W.A. captured national attention with unflinching depictions of police brutality and injustice, provoking outrage from law enforcement and even drawing the ire of the FBI. Yet despite, or perhaps because of, their raw defiance, they achieved immense commercial success, proving that political authenticity and popular appeal could coexist. Their breakthrough carved a path for future generations of hip-hop artists to wield their platforms as instruments of social commentary and resistance.

At the same time, this era exposed the uneasy tension between political integrity and commercial ambition. This dynamic that would haunt protest music in the decades to follow. As hip-hop ascended to mainstream dominance, questions emerged: could radical messages retain their potency within the machinery of a profit-driven industry? Could voices of dissent remain uncompromised amid brand deals, chart placements, and corporate control? The 1990s, for all their revolutionary energy, marked the beginning of a new dilemma - how to speak truth to power from inside the very structures that power built.

The Digital Age Awakening: 2005

The post-9/11 era infused protest music with renewed urgency, crystallized in Green Day’s “American Idiot” (2004)—the defining anthem of the 2005 moment. Structured as a modern rock opera, the album offered a scathing, wide-ranging indictment of the Bush administration’s politics, from war and media manipulation to cultural conformity. Yet despite its pointed critique, American Idiot achieved remarkable commercial success, topping charts and resonating with a generation disillusioned by fear-driven nationalism.

Its impact affirmed that, even in an era increasingly dominated by hip-hop, rock music still had the power to channel dissent and shape political discourse. Green Day’s fusion of narrative ambition, raw emotion, and mainstream appeal reinvigorated the genre’s role in protest culture, proving that the electric guitar had not yet gone silent in the struggle for a better world.

The 2000s marked a pivotal shift in the evolution of protest music, as the digital revolution redefined how political expression found its audience. With the rise of the internet, artists could distribute their music instantaneously, bypassing traditional gatekeepers like radio stations and record labels. Platforms such as YouTube democratized access to both creation and consumption, allowing protest songs to circulate widely without institutional backing. This transformation fundamentally altered the dynamics of musical activism, liberating it from commercial constraints and opening space for more voices to be heard.

At the same time, mainstream pop artists began to engage more openly with political themes. Figures like P!nk and the Black Eyed Peas addressed issues of war, inequality, and national division with a boldness that would have once been deemed commercially risky. Their success signaled a shift in public appetite. Audiences were increasingly willing to embrace entertainment that carried a message, blurring the line between pop culture and political discourse.

Yet the 2000s also laid bare a new challenge: in an increasingly fragmented media landscape, it became harder for any single protest anthem to achieve the unifying cultural resonance of past classics like “We Shall Overcome” or “Blowin’ in the Wind.” Without common platforms or shared listening experiences, the power of protest music risked becoming more diffuse, its reach wider, perhaps, but its impact more dispersed.

The Social Media Era: 2015

The 2010s ushered in a new era of protest music, one shaped and amplified by the transformative power of social media. At the forefront stood Kendrick Lamar’s “Alright” (2015), which rose to prominence as the unofficial anthem of the Black Lives Matter movement. Its evolution from studio track to street chant, captured the profound ways in which music and activism now intersect in real time. When demonstrators in Cleveland chanted its refrain during a tense confrontation with police, they revealed a deeper truth: in the digital age, protest music is no longer just a form of artistic expression, it is a living, breathing tool of resistance, capable of galvanizing solidarity and amplifying collective voices.

Lamar’s inspiration for “Alright” emerged from a visit to Nelson Mandela’s prison cell on Robben Island, a symbolic link with global liberation movements. That connection reflected a broader shift in the nature of protest itself: in the age of social media, local acts can ignite global waves of solidarity. Through “Alright,” Lamar not only gave voice to a generation’s hope; he positioned protest music as a force that transcends borders, cultures, and platforms, capable of binding global movements together in shared purpose and song.

In the 2010s, the visual dimension of protest music became as vital as the sound itself. Music videos such as Childish Gambino’s “This Is America” (2018) captivated global audiences not only through rhythm and lyric, but through searing visual storytelling with layered imagery that confronted viewers with stark portrayals of gun violence and injustice. These multimedia expressions expanded the boundaries of protest art, pushing artists to think beyond the traditional structure of the protest song and embrace a more cinematic, symbolic form of political commentary.

Yet this era also exposed the paradox of social media activism. Platforms like Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube could catapult protest messages to millions within moments, but their speed and virality often came at a cost. Artists were more visible and more vulnerable, subject to immediate backlash, distortion, or politicization. Complex political statements could be flattened into soundbites, stripped of nuance in the race for clicks and shares. The very tools that gave protest music its reach also risked eroding its depth. In this fast-moving digital landscape, the contemplative force that once defined the most enduring protest songs had to compete with an attention economy increasingly driven by reaction rather than reflection.

The Streaming Revolution: 2025

The contemporary era offers protest music both unprecedented possibilities and profound new challenges. Unlike earlier decades, which often rallied around singular anthems, the 2020s unfold within a fragmented and decentralized cultural landscape. Today, multiple voices speak to social injustice across a range of platforms, each resonating within its own niche. The rise of TikTok and short-form media has radically reshaped how protest music circulates, where a 15-second clip can go viral and reach millions, yet rarely carry the sustained emotional arc or narrative depth that once defined the genre.

At the same time, the streaming economy has democratized access to music production and distribution, empowering artists to bypass traditional industry gatekeepers and release politically charged work on their own terms. Yet this freedom is tempered by new, subtler forms of censorship. Algorithmic suppression and opaque content moderation policies often sideline songs that address controversial or politically sensitive themes. While not explicitly banned, such tracks may be quietly buried. They are often denied visibility by the very platforms that made their creation possible. In this new landscape, protest musicians must not only confront the injustices they sing about, but also navigate the digital architectures that shape who hear their voices, and who doesn’t.

Contemporary protest music mirrors the global, interconnected fabric of modern social movements. In today’s digital age, a local uprising can spark musical responses across continents within hours. Artists now collaborate across borders to confront shared challenges of climate change, economic inequality, democratic erosion, creating a rich, transnational dialogue through song. This global perspective has undeniably broadened the scope and resonance of protest music, yet it has also, at times, diluted the intimate, community-rooted character that defined earlier eras of musical activism.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the worldwide protests of 2020 revealed both the immense potential and the inherent limitations of protest music in the digital age. Artists could respond to unfolding events with unprecedented speed, and their messages could reach a truly global audience. But the absence of shared physical spaces—streets filled with voices, rallies echoing with song—diminished music’s traditional role in forging collective identity and emotional solidarity. Virtual concerts and digital activism helped bridge the divide, yet they could not fully replicate the visceral, unifying force of voices raised together in public gatherings. In this new era, protest music continues to evolve, resonant and far-reaching, yet still searching for the communal heartbeat that once gave it its fiercest power.

Conclusion: The Enduring Power of Musical Activism

Over the course of my eight decades witnessing social change, popular music has consistently served as both a mirror reflecting society’s struggles and a catalyst propelling movements forward. From Woody Guthrie’s haunting folk ballads to today’s viral TikTok anthems, the evolution of protest music reveals a striking continuity: while its forms and platforms have shifted with each technological and cultural wave, its role in activism has remained remarkably constant.

he most enduring protest songs possess a few timeless qualities. They give voice to collective emotions that simmer just beneath the surface, feelings of injustice, yearning, and a deep, often fragile hope that our better angels might yet prevail. With lyrics that resonate and refrains that linger, they invite communal participation, transforming private anguish into shared resolve. Through the power of rhythm and word, these songs weave individual voices into a chorus of solidarity, reminding us that in the face of adversity, we do not stand alone.

And above all, they are rooted in lived experience. Whether born from Sam Cooke’s encounter with racial discrimination in “A Change Is Gonna Come,” or Kendrick Lamar’s transformative visit to Mandela’s prison cell inspiring “Alright,” the most powerful protest music emerges not from abstraction, but from the raw, authentic intersection of personal truth and political reality. It is there in that fusion of heart and history that song becomes movement.

The technological journey from sheet music to streaming has profoundly reshaped the way protest music travels and touches society. In earlier eras, protest songs relied on physical gatherings, marches, union halls and coffeehouses where shared spaces fostered collective experience and cultural cohesion. Their power grew not only through melody, but through presence, repetition, and communal voice.

Today, protest music can reach global audiences in an instant, crossing borders and platforms at the speed of a click. This digital age has democratized musical activism, amplifying voices that once would have gone unheard. Yet this same decentralization has come at a cost: the erosion of shared cultural touchstones. With audiences scattered across infinite streams and algorithms, the unifying force that once gave protest songs their enduring resonance is more difficult to achieve. In gaining immediacy and reach, contemporary protest music often struggles to cultivate the sustained, collective momentum that once defined its power.

Footnote

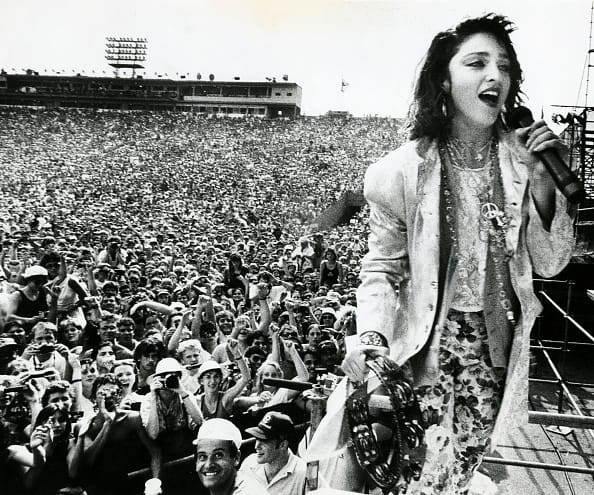

As a footnote to this reflection on the power of protest music, I was honored to serve as Executive Producer of Live Aid—an event widely regarded as one of the largest global television broadcasts in history, and unquestionably the most ambitious music concert the world has ever seen. On July 13, 1985, an estimated 1.9 billion people across 150 countries tuned in to witness a moment unlike any before it: music uniting the planet in real time.

Live Aid was more than a concert; it was a cultural watershed, demonstrating the profound capacity of music not only to entertain but to mobilize compassion and transcend geopolitical divides. For the first time, audiences in China and the Soviet Union were part of a simultaneous global broadcast, an unprecedented act of connection during the final decade of the Cold War. At a time when many Western governments, including the United States, were hesitant or outright opposed to intervening in Ethiopia’s devastating famine with 6 million lives at stake, the global music community rose in defiance of political indifference. Artists and organizers came together to form a worldwide chorus of conscience, raising what would amount to over $400 million in today’s dollars to support relief efforts and save millions of lives.

In tribute to the rich legacy of American protest music, we chose to open the U.S. broadcast from Philadelphia with Joan Baez, a voice synonymous with courage and conscience, singing her timeless rendition of Amazing Grace. Her performance served as a spiritual invocation, honoring the tradition of music as resistance and reminding the world that grace, when channeled through solidarity, can become a force for tangible change.

Live Aid stands as enduring proof that when artists raise their voices not just in harmony, but in purpose, they can shift the moral compass of the world.

Celebrate the 40th Anniversary of Live Aid A Global Broadcast Special on CNN and BBC – Airing July 13

Join us for a landmark international television event as CNN and BBC come together to honor the 40th anniversary of Live Aid, the concert that changed the world.

On July 13, relive the extraordinary moment when music united humanity in a single, breathtaking act of global solidarity. First broadcast in 1985 to an estimated 1.9 billion viewers across 150 nations, Live Aid was more than the largest concert in history—it was a turning point in the power of collective action. From London to Philadelphia, from Moscow to Beijing, it was the first time the world truly felt like a global village.

Now, four decades later, we invite a new generation to rekindle the spirit of unity and compassion that once lit up the world—a spirit we need now more than ever.