The Uncomfortable Truth

The fight against climate change, once framed as a collective global endeavor requiring urgent action and shared sacrifice, is faltering. Decades of warnings from scientists, punctuated by increasingly severe climate impacts manifesting across the globe, have seemingly failed to dislodge institutional inertia and the entrenched interests prioritizing short-term economic gains over long-term planetary health. While pronouncements of commitment continue to echo in corporate boardrooms and government halls, a closer examination reveals a disturbing pattern: a widespread and accelerating retreat from meaningful climate action by the very institutions best positioned to lead the transition. We have, for now, lost the battle against limiting Greenhouse Gas Emissions, not due to a lack of scientific understanding, or technological capability, but because established powers – major fossil fuel corporations, national governments, and the financial institutions that fuel the global economy – have chosen to abandon or significantly weaken their climate commitments in pursuit of profit and political expediency.

The evidence is stark and multifaceted. Major oil and gas companies, after brief flirtations with green branding, are doubling down on their core fossil fuel businesses, scaling back renewable investments, and weakening emission reduction targets. Governments, including those in historically leading nations like the United States and the United Kingdom, are rolling back crucial climate policies, delaying transition deadlines, and actively promoting continued fossil fuel extraction, often justifying these reversals with appeals to short-term economic stability or consumer costs. Simultaneously, large financial institutions, facing political backlash and legal threats orchestrated by anti-climate forces, are withdrawing from climate alliances and stepping back from ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) principles, thereby reducing pressure on high-emitting industries. Even market forces, often touted as a potential driver of change, are contributing to the problem, as seen in the recent resurgence of coal-fired power generation in the US, driven by its temporary price competitiveness with natural gas.

This report provides an extensive examination of this great reversal. It delves into specific cases, citing the actions and stated rationales of key players in the oil industry, government, and finance. We will explore how US laws and policies are being reshaped to favor fossil fuels, how the promise of international climate agreements is being undermined by national inaction, and how the pervasive influence of short-term profit motives systematically overrides long-term environmental considerations. We will quantify the devastating environmental impact of these decisions, drawing on authoritative scientific assessments like those from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) to illustrate the trajectory towards catastrophic warming that these rollbacks entail.

However, acknowledging the loss of this battle does not necessitate surrender in the war for a habitable planet. There are potential pathways forward. Recognizing that solutions relying on the voluntary action of the current establishment have proven insufficient, we must explore strategies centered on personal adaptation, the necessary adjustments individuals and communities will need to make to cope with unavoidable climate impacts, and the power of social movements. Grassroots activism, strategic litigation, and diverse forms of civil disobedience may be the only options available to challenge entrenched interests, build public will, and potentially force the systemic changes that institutional leadership has failed to deliver. The need is urgent, the findings are critical, but the ultimate aim is to confront the uncomfortable truth of our current predicament and identify realistic, albeit challenging, avenues for reclaiming the future.

The Great Reversal ss Big Oil Doubles Down

Nowhere is the retreat from climate responsibility more blatant or consequential than within the boardrooms of the world's largest fossil fuel corporations. These entities, whose historical and ongoing operations are the primary drivers of anthropogenic climate change, briefly courted public approval and investor confidence with pledges of transition and commitments to net-zero emissions. Yet, beneath the veneer of greenwashing, a stark reversal is underway. Faced with the enduring profitability of their core business and mounting pressure from shareholders demanding maximum returns, major oil and gas companies are demonstrably abandoning their green ambitions, weakening climate targets, and doubling down on the very fossil fuel extraction that jeopardizes a stable climate. The following briefly details the specific strategic shifts and broken promises that exemplify Big Oil's betrayal of climate commitments.

Masterclass in Diluted Ambition

Shell, a titan of the global energy industry, provides a particularly illuminating case study in the erosion of corporate climate goals. In its updated Energy Transition Strategy 2024 (ETS24), the company executed a subtle but significant weakening of its climate targets, signaling a clear shift back towards its fossil fuel base. The most prominent change was Shell's decision to completely scrap its medium-term target for 2035. The company had previously committed to a 45% reduction in NCI by 2035, a crucial milestone on the path to net zero. This target was unceremoniously 'retired' in the ETS24 update, precisely as it was about to fall within Shell's critical 10-year strategic planning horizon. Shell's CEO, Wael Sawan, reportedly dismissed attempts to maintain focus on the 2035 goal, calling detailed scrutiny of emissions beyond the short term 'perilous.’ This abandonment of a key medium-term objective effectively removes a vital checkpoint for assessing Shell's transition progress and allows the company to defer meaningful action well into the future.

Shell attempted to mask this retreat with a 'new ambition' focused on reducing customer emissions (Scope 3) specifically from the use of its oil products by 15-20% by 2030. Scope 3 emissions encompass all indirect greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions that occur in a company's value chain, excluding those from owned or directly controlled sources (Scope 1) and indirect emissions from purchased energy (Scope 2). However, this ambition is deeply flawed. Firstly, it only addresses emissions from oil products, conveniently ignoring the significant and growing emissions from Shell's expanding natural gas business, thus covering only about half of the company's total Scope 3 footprint. Secondly, analysis by organizations like ‘Follow This’ suggests that much of this targeted reduction had likely already been achieved through prior refinery divestments and accounting adjustments, rather than representing new decarbonization efforts. The simultaneous weakening of the overall NCI target, which covers all energy products, further exposes the inadequacy of this narrow, oil-focused ambition.

Instead of investing in genuine decarbonization, Shell's strategy clearly prioritizes the expansion of its fossil fuel operations, particularly in Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG). The ETS24 explicitly outlines plans to grow Shell's LNG business by a substantial 20-30% by 2030 compared to 2022 levels. This expansion locks in decades of future emissions and directly contradicts the scientific consensus requiring a rapid phase-out of fossil fuels. Furthermore, Shell has also backtracked on other aspects of its climate strategy, abandoning previous targets to invest significantly ($100m per year) in carbon credit projects and reportedly scaling back investments in new offshore wind projects while restructuring its power division to refocus on its profitable oil, gas, and biofuels segments. Shell's actions demonstrate a clear strategic pivot away from the energy transition and back towards maximizing profits from fossil fuels, undermining its own stated climate goals.

BP’s "Fundamental Reset" Towards Fossil Fuels

BP's reversal on climate commitments has been perhaps even more explicit than Shell's. Under CEO Murray Auchincloss, the company announced a "fundamental reset" of its strategy in early 2025, openly abandoning the greener ambitions championed by his predecessor, Bernard Looney. This reset unequivocally prioritizes fossil fuel production and maximizing shareholder value over the previously touted transition to an integrated energy company.

The numbers speak for themselves. BP significantly increased its planned investment in oil and gas operations to a hefty $10 billion per year. Concurrently, it slashed more than $5 billion from its previously announced green investment plan, signaling a dramatic reduction in its commitment to low-carbon energy. The company stated it would now be "very selective" about its low-carbon investments, a clear euphemism for deprioritizing renewables and other transition technologies.

This strategic shift is directly reflected in BP's production targets. The company now aims to produce 2.4 million barrels of oil and gas equivalent per day by 2030. This target is a staggering 60% higher than the production level envisioned in its net-zero plan announced just five years prior, representing a massive increase in projected fossil fuel output and associated emissions.

The rationale provided for this U-turn centers on perceived economic realities and investor demands. Auchincloss cited "misplaced" optimism regarding the speed of the global energy transition, claiming the company had previously "went too far, too fast" with its green pledges. This narrative conveniently aligns with pressure from investors who were dissatisfied with BP's lagging share price compared to rivals like ExxonMobil and Chevron, which had maintained a stronger focus on fossil fuels. The emergence of activist investors, such as Elliott Management, demanding higher returns further incentivized the pivot back to the perceived safety and profitability of oil and gas. Alongside this strategic redirection, BP announced plans for $20 billion in asset sales and significant cost reductions, further emphasizing the focus on short-term financial performance.

U.S. Oil Giants

While European counterparts like Shell and BP have made more explicit U-turns on previously announced green ambitions, US oil giants Chevron and ExxonMobil have largely maintained a strategy that critics argue never truly embraced the scale of emission reductions required by the Paris Agreement. Rather than abandoning ambitious targets, their approach has consistently prioritized maximizing fossil fuel production while focusing emission reduction efforts primarily on operational efficiency (Scope 1 and 2 intensity) and investing in technologies like carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) rather than significantly scaling back core oil and gas operations. Chevron, for instance, set targets to reduce the carbon intensity of its production but faced criticism for avoiding absolute reduction goals and robust targets for Scope 3 emissions, which constitute the vast majority of emissions associated with its products. Recent reports also indicate Chevron significantly cut spending on green initiatives amid financial pressures.

Similarly, ExxonMobil promotes its "Advancing Climate Solutions" strategy and a 2050 net-zero ambition for operated assets, highlighting investments in CCUS and hydrogen. However, analyses reveal that its planned investments in traditional oil and gas significantly dwarf those in lower-emission solutions, and the company lacks comprehensive Scope 3 targets, leading organizations like ClientEarth to label its efforts as greenwashing. Therefore, while not necessarily an overt "abandonment" of previously strong commitments in the same vein as BP, the continued strategic focus on fossil fuel expansion and the inadequacy of their emission reduction plans relative to climate science indicate a persistent refusal by Chevron and ExxonMobil to fundamentally alter their business models, effectively sidelining the rapid and deep emission cuts needed across their value chains.

The Common Denominator - Profit Over Planet

The actions of the Oil Majors are symptomatic of a broader trend within the oil and gas industry. While rhetoric may vary, the underlying driver is consistent: the prioritization of short-term shareholder value and the immense profitability of existing fossil fuel assets over meaningful investment in a rapid and just energy transition. The industry's retreat underscores the fundamental conflict between its core business model and the requirements of climate stability, revealing that voluntary commitments are easily discarded when they clash with shareholder imperative to maximize profit.

Government Policy Reversals and Fossil Fuel Enablement

While corporate actors bear significant responsibility for driving climate change, national governments possess the unique authority and obligation to establish regulatory frameworks, guide economic transitions, and uphold international commitments. Yet, mirroring the corporate retreat, governments worldwide, including those previously positioning themselves as climate leaders, are increasingly abandoning the helm. Driven by short-term political calculations, economic anxieties, and the persistent influence of fossil fuel lobbies, nations are actively weakening climate policies, delaying crucial transition measures, and continuing to enable the expansion of the very industries fueling the crisis.

A critical yet often underappreciated dimension of this inertia is the role of state-owned oil companies (NOCs), which collectively produce about 55% of the world's oil and gas and control up to 90% of global reserves. These entities, directly accountable to their governments, are expanding production despite international climate commitments. Saudi Aramco, the world's largest oil company and 90% state-owned, reported a net income of $106.2 billion in 2024 and plans to increase its gas production capacity by more than 60% by 2030 compared to 2021 levels. PetroChina, Asia's largest oil and gas producer, achieved a record net profit of $22.7 billion in 2024, driven by increased oil and gas output. Gazprom, Russia's state-controlled gas giant, plans to increase its gas production to around 416 billion cubic meters in 2024, up by 61 billion cubic meters compared to the previous year. And Equinor, majority-owned by the Norwegian government (67%), is projected to increase oil and gas output from 2024 totals.

These examples underscore a troubling reality: the world's largest oil companies, owned by governments, are not decreasing output. Instead, they are expanding production, even as global climate goals demand a swift transition away from fossil fuels. This governmental complicity, both through direct ownership and policy decisions, poses a significant barrier to meaningful climate action.

The United States: Deregulation and Drilling Despite Pledges

The United States presents a complex and often contradictory picture regarding climate action. Despite rejoining the Paris Agreement and enacting significant climate-related legislation like the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) under the Biden administration, subsequent actions by the Trump Administration and ongoing practices reveal a persistent tension between stated climate goals and the powerful inertia of the fossil fuel economy, culminating in significant rollbacks under shifting political winds.

A stark example emerged in March 2025, when the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), under the new leadership of Administrator Lee Zeldin, announced a sweeping review aimed at dismantling key climate regulations. Zeldin heralded the plan to reconsider 31 existing rules and policies – primarily targeting climate change and fossil fuel pollution – as potentially "the greatest day of deregulation our nation has seen.’ While the specific outcomes remain subject to lengthy regulatory and legal processes, the intent was clear: to unwind environmental protections established under previous administrations, including crucial rules designed to limit climate pollution from power plants. This move, following earlier executive actions to halt funding for climate projects under the IRA and Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, signaled a decisive shift away from federal climate leadership, prioritizing the reduction of perceived burdens on industry over environmental protection.

Beyond explicit deregulation, the continued high rate of fossil fuel extraction approvals on public lands starkly contradicts climate commitments. Despite campaign promises to end new federal oil and gas leasing, the Biden administration approved a staggering 6,430 permits for drilling on public lands during its first two years (2021-2022). This figure notably outpaced the 6,172 permits approved by the Trump administration over its first two years, demonstrating a continuity of fossil fuel expansion regardless of political rhetoric. These permits, heavily concentrated in states like New Mexico and Wyoming, are estimated to lock in over 800 million tons of future greenhouse gas pollution – equivalent to the annual emissions of roughly 217 coal-fired power plants. Furthermore, after an initial pause, the Biden administration actively restarted and expanded oil and gas leasing, including a massive 80-million-acre offering in the Gulf of Mexico shortly after making international climate pledges at COP26. While some policy reforms, such as increased royalty rates and bonding requirements, were eventually introduced, they primarily addressed the financial terms of leasing rather than fundamentally constraining the volume of extraction, illustrating a reluctance to challenge the core drivers of fossil fuel production.

On April 29, 2025 in a significant move that has raised alarm among scientists and policymakers, the Trump administration has dismissed nearly 400 contributors to the Sixth National Climate Assessment (NCA), a congressionally mandated report that evaluates the impacts of climate change across the United States. This action effectively halts the progress of a critical scientific endeavor designed to inform federal and local decision-making on climate-related issues. The NCA, overseen by the U.S. Global Change Research Program (USGCRP), synthesizes research from 14 federal agencies and has been a cornerstone in understanding regional climate effects, such as coastal flooding, droughts, and agricultural shifts. The abrupt dismissal of its contributors not only disrupts the continuity of this vital report but also undermines the scientific integrity of the assessment process.

This development is part of a broader pattern of the Trump administration's outright denial of climate science, calling it a hoax. These actions reflect an attempt to suppress scientific findings that may conflict with the administration's policy objectives, particularly regarding fossil fuel interests. By sidelining expert voices and disrupting established scientific processes, the administration is leaving the nation ill-prepared to address the escalating challenges posed by climate change.

The United Kingdom: A "Pragmatic" Retreat from Leadership

The United Kingdom, host of the COP26 climate summit and a nation with legally binding net-zero targets, executed a significant and widely criticized U-turn on key climate policies in September 2023. Prime Minister Rishi Sunak announced the rollbacks under the guise of a "more pragmatic, proportionate and realistic approach," while paradoxically claiming continued commitment to the overarching 2050 net-zero goal. This reframing served as political cover for delaying and weakening several crucial decarbonization measures.

The most high-profile reversal was the five-year delay in the ban on selling new petrol and diesel cars, pushing the deadline from 2030 to 2035. This move significantly weakened a flagship policy designed to accelerate the transition to electric vehicles, sending confusing signals to the automotive industry and consumers alike.

Similarly, targets for decarbonizing home heating were substantially weakened. The ban on installing new fossil fuel heating systems (like oil boilers) in homes off the gas grid was pushed back nearly a decade, from 2026 to 2035. While the phase-out date for selling new gas boilers remained nominally 2035, significant exemptions were introduced for potentially a fifth of households, and Sunak controversially suggested that millions might "never" have to make the switch if deemed too expensive, effectively undermining the policy's intent.

Furthermore, Sunak explicitly committed to never banning new oil and gas exploration and extraction licenses in the North Sea, directly contradicting the scientific consensus that no new fossil fuel infrastructure can be built if climate goals are to be met. Plans that might have mandated energy efficiency upgrades for homes were also scrapped. These decisions were justified by the government as necessary to avoid imposing "unacceptable costs" on households, framing ambitious climate action as economically burdensome and politically unpalatable.

Global Implications: A Failure of Governance

The actions of the US and UK are not isolated incidents but reflect a broader global trend where national interests, short-term economic pressures, and the ascendance of right-wing political factions severely impede collective climate action. Similar patterns of delayed ambition, policy weakening, and continued fossil fuel subsidies can be observed in numerous other countries, including major emitters like Saudi Arabia, which continues to heavily invest in expanding oil production capacity while making limited progress on diversification pledges. The failure of governments to implement policies consistent with their own stated climate goals, often while simultaneously facilitating fossil fuel expansion, represents a profound failure of governance. It demonstrates the immense difficulty of enacting transformative change within existing political and economic structures that remain deeply intertwined with fossil fuel interests. This governmental retreat leaves a critical void in climate leadership, shifting the burden onto individuals and non-state actors while significantly increasing the risks of catastrophic climate change.

Finance Industry Follows Suit

The global financial system, the engine that powers the modern economy, holds immense potential to either accelerate or derail the transition to a low-carbon future. Through investment decisions, lending practices, and shareholder influence, financial institutions possess the leverage to steer capital away from polluting industries and towards sustainable solutions. Recognizing this power, and facing growing pressure from investors, regulators, and the public, the financial sector made significant strides in recent years towards embracing climate considerations. The rise of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) investing principles and the formation of high-profile climate alliances, such as the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net-Zero (GFANZ) launched in 2021 and its banking sub-group, the Net-Zero Banking Alliance (NZBA), signaled a potential turning point. These initiatives, while often voluntary and subject to criticism regarding standardization and potential greenwashing, represented a public acknowledgment of climate risk and a commitment, at least rhetorically, to align financial activities with the goals of the Paris Agreement.

However, this burgeoning commitment has proven fragile and highly susceptible to prevailing political and economic headwinds. Just as oil companies and governments have retreated from their climate pledges, the financial sector is now backpedaling. Major banks and asset managers are quietly, and sometimes openly, withdrawing from climate alliances, diluting ESG commitments, and signaling a return to prioritizing short-term financial metrics above long-term climate stability. This retreat represents a critical failure, removing a vital source of pressure on high-emitting industries and undermining the financial architecture needed for a successful climate transition.

The Exodus from Climate Alliances

The most visible manifestation of this retreat has been the withdrawal of major financial players from voluntary climate alliances, particularly the UN-convened Net-Zero Banking Alliance (NZBA). In late 2024 and early 2025, a cascade of announcements saw prominent US financial institutions abandon the initiative. Morgan Stanley, Wells Fargo, Citibank, Goldman Sach, JP Morgan and Bank of America all declared their departure from the NZBA. This exodus left the alliance significantly weakened, particularly in the US market. This withdrawal is not merely symbolic; it signals a walking away from the NZBA's goal of aligning financing activities with net-zero emissions by 2050 and cuts the collective pressure on members to set and meet interim targets.

This trend extends beyond the NZBA. Reports indicate a broader pattern of banks and asset managers rolling back both climate and, often relatedly, Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) commitments since late 2024. This suggests a wider chilling effect on corporate responsibility initiatives perceived as potentially controversial or financially burdensome in the short term.

Drivers of the Financial Retreat: Politics, Pressure, and Profit

The financial sector's pullback from climate commitments is not occurring in a vacuum. It is a direct response to a confluence of powerful pressures, primarily stemming from a coordinated rightwing political backlash against ESG principles in the United States.

A significant driver is the intense political pressure exerted by the Republican party and conservative media outlets. ESG has been aggressively framed as "woke capitalism," an elitist agenda detrimental to free-market principles, and an attack on the fossil fuel industry. High-profile political figures, including President Trump, have targeted climate alliances, labeling them "climate cartels.” This rhetoric creates a hostile environment for financial institutions attempting to integrate climate considerations into their strategies, making continued participation in climate initiatives politically risky.

This political backlash has translated into concrete legislative action in several Republican-led states, directly penalizing financial institutions perceived as boycotting fossil fuels. Texas enacted laws prohibiting state agencies from contracting with or investing in such companies and mandating divestment. Florida passed similar legislation (HB 3, HB 1645) forbidding the consideration of ESG factors in state and local government investment and contracting decisions, demanding that choices be based solely on "pecuniary factors.” These laws create direct financial disincentives for banks and asset managers to limit fossil fuel financing or participate in climate initiatives.

Financial institutions are also facing increased legal scrutiny and the threat of litigation related to their ESG practices and climate commitments. A prominent example is the lawsuit led by Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton, joined by other Republican states, targeting major asset managers like BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street. The suit alleges antitrust violations, claiming these firms used their market influence and membership in climate groups to collude against the fossil fuel industry (specifically coal producers), thereby artificially inflating energy costs. Regardless of the legal merits, such lawsuits create significant legal costs, reputational risks, and uncertainty, further discouraging institutions from maintaining strong climate stances.

The fact that many climate alliances like the NZBA are voluntary, non-binding initiatives makes it relatively easy for members to withdraw when faced with external pressure. Unlike legally mandated regulations, there are no immediate legal penalties for abandoning these commitments, making them disposable when political or economic winds shift.

Faced with this multi-pronged assault, many financial institutions are choosing the path of least resistance, prioritizing the avoidance of short-term political, legal, and financial risks over upholding their public climate pledges. While some may claim to be continuing climate efforts quietly – a practice dubbed "greenhushing" – the lack of transparency and public accountability makes it difficult to assess the sincerity or effectiveness of such claims. The overall effect is a clear reduction in the financial sector's ambition and willingness to support climate action.

Implications: Undermining the Transition

The retreat of major financial institutions from climate commitments has profound implications. It weakens a crucial lever for change by eliminating financial pressure on corporations to decarbonize. It signals to the market that climate risk will not be treated as a core financial risk, leading to the continued mispricing of assets and perpetuation of investments in high-carbon infrastructure. Furthermore, it undermines investor confidence in the credibility of corporate climate pledges and complicates efforts to mobilize the vast amounts of private capital needed to finance the energy transition. By succumbing to short-term pressures and political expediency, the financial establishment is not only abandoning its own stated goals but playing a key role in actively hindering the global effort to avert climate catastrophe.

How Market Forces Are Bringing Back Coal

While high-level corporate strategies and government policies represent deliberate choices to abandon climate commitments, the insidious nature of short-term economic thinking can also undermine climate progress through seemingly mundane market dynamics. A stark illustration of this is the recent, albeit potentially temporary, resurgence or stabilization of coal-fired power generation in the United States. Despite a long-term decline from its peak usage, coal, the most carbon-intensive fossil fuel, is experiencing moments of renewed competitiveness driven primarily by fluctuations in the price of natural gas. This phenomenon underscores how deeply ingrained fossil fuels remain in the energy system and how easily market volatility can trigger backward steps, prioritizing immediate cost savings over long-term climate stability.

Data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) reveals this troubling trend. In February 2025, for instance, electricity generation from coal saw an increase compared to the previous year across almost all regions of the United States. Crucially, the share of electricity generated from coal also rose in most areas, directly displacing generation from natural gas. While this specific period represents a snapshot, it highlights a vulnerability in the energy transition: the persistent reliance on fossil fuels and the sensitivity of fuel choices to market prices.

The primary driver behind this coal comeback is simple economics: price competitiveness with natural gas. Natural gas prices are notoriously volatile, influenced by factors like weather patterns (affecting heating demand), storage levels, export demand, and production rates. When natural gas prices rise, or even when they simply fail to maintain a significant cost advantage over coal, power producers with the flexibility to switch fuels are incentivized to burn more coal to minimize operational costs. In February 2025, the EIA reported that the Henry Hub natural gas spot price, when converted to an equivalent energy content basis ($/MWh), was only slightly below the price of Central Appalachian coal ($34.13/MWh for gas vs. $35.60/MWh for coal). This narrow price difference, coupled with regional variations and existing fuel contracts, made coal an economically viable, and in some cases preferred, option for power generation during that period (EIA Electricity Monthly Update, Feb 2025 data). The EIA notes that such shifts are not uncommon, particularly during winter months in regions like the Northeast, where high demand for natural gas for heating can drive up its price or constrain pipeline capacity available for power plants.

The environmental cost of this economic calculus is severe. Coal-fired power plants emit more than twice the amount of CO₂ compared to natural gas-fired plants for the same amount of electricity generated not to mention higher levels of other harmful pollutants like sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and particulate matter. Every megawatt-hour generated from coal instead of a cleaner source represents a setback for climate mitigation efforts. The fact that short-term fluctuations in commodity prices can trigger an increased reliance on the dirtiest fossil fuel highlights the inadequacy of relying solely on market forces to drive decarbonization. Without strong policy interventions – such as robust carbon pricing, stringent emissions standards for power plants, and accelerated investment in renewable energy and grid flexibility, the energy system remains susceptible to prioritizing immediate cost optimization over the urgent need to reduce emissions.

Despite global efforts to reduce coal consumption, Many of the largest countries throughout the world have maintained or increased their reliance on coal in recent years. In 2023, China increased its coal consumption by 6%, accounting for over 56% of global demand. The country initiated construction of 99.5 gigawatts (GW) of new coal capacity in 2024, citing the need for reliable baseload power alongside intermittent renewables. India's coal consumption rose by 8% in 2023, driven by increased demand in the power sector and industry. The country continues to invest in coal to meet its growing energy needs. Indonesia's coal consumption increased by 11% in 2023. The nation is expanding its coal production and consumption to support economic growth. In 2023, coal constituted 62 percent of the Philippines' electricity generation, up from 59 percent in 2022. This marks the highest level since 2016, indicating a growing dependence on coal-fired power. Another example, Kazakhstan hit new records in coal production and consumption levels last year and is expected to increase coal consumption further, building new coal power plants to meet energy demands.

This global coal resurgence, driven by the simple fact that it is cheaper, or more accessible or becomes temporarily cheaper than gas, serves as a potent reminder that the battle against climate change is not only fought in boardrooms and legislative chambers but also in the day-to-day operational decisions of the energy sector. It demonstrates how deeply entrenched the fossil fuel economy remains and how easily progress can be reversed when short-term economic considerations are allowed to dominate decision-making, further contributing to the widening gap between climate rhetoric and reality.

Short-Term Profit Over Long-Term Survival

We are experiencing a global pattern of retreat and reversal across key sectors – fossil fuel corporations prioritizing low-cost production, governments rolling back regulations, and financial institutions weakening climate commitments. While the specific justifications vary – shareholder pressure, political expediency, market volatility , a common thread runs through these decisions: the pervasive dominance of short-term profit motives over long-term environmental sustainability. The established economic and political systems are fundamentally structured to reward immediate financial gains, making it exceedingly difficult, if not impossible within the current paradigm, to enact the comparatively rapid, transformative changes required to address the climate crisis effectively.

For fossil fuel corporations, the calculation is brutally simple. Despite acknowledging climate risks, their core business remains the extraction and sale of oil and gas, activities that continue to generate immense profits. Investments in renewable energy, while potentially beneficial in the long run, offer lower or less certain returns in the near term compared to established fossil fuel operations. When faced with investor pressure demanding higher dividends and share prices now, the strategic choice inevitably leans towards maximizing returns from existing, high-emitting assets. Weakening climate targets and boosting fossil fuel production is a rational decision within a system that prioritizes quarterly earnings reports above all else. The long-term costs of climate change, borne by society as a whole, are externalized and discounted, while the immediate profits are privatized and maximized.

Governments, theoretically positioned to counteract these market failures, are themselves captive to short-term cycles and pressures. Political survival often depends on maintaining economic stability and minimizing immediate costs for consumers and businesses. Ambitious climate policies, such as carbon pricing, phasing out fossil fuel subsidies, or mandating rapid transitions in sectors like transport and heating, face significant public resistance if perceived as increasing costs or disrupting established industries. Politicians, focused on the next election cycle, are often reluctant to impose measures with immediate costs, even if the long-term benefits (avoiding climate damages) are far greater. This dynamic is evident in the UK government's justification for rolling back green targets, citing the need to avoid "unacceptable costs" for households, and in the US, where deregulation is framed as boosting the economy, ignoring the long-term economic devastation climate change will bring. Furthermore, the immense lobbying power of the fossil fuel industry ensures that its interests remain deeply embedded in policymaking, further hindering efforts to enact meaningful climate legislation.

Financial institutions, acting as intermediaries and allocators of capital, are similarly constrained. While ESG principles gained traction, the recent backlash demonstrates how quickly these considerations can be abandoned when they conflict with perceived fiduciary duty (narrowly defined as maximizing short-term financial returns) or expose institutions to political and legal risks. The pressure from anti-ESG state legislation and lawsuits creates a powerful incentive for banks and asset managers to revert to traditional financial metrics, effectively ignoring climate risk or treating it as a secondary concern. Financing continues to flow towards profitable fossil fuel projects because the immediate returns are clear and quantifiable, while the systemic risks associated with climate change are harder to price and fall outside the typical investment horizon.

Even market fluctuations, like the temporary price advantage of coal over natural gas, illustrate this short-term bias. Power producers opt for the cheaper, dirtier fuel to minimize immediate operating costs, externalizing the environmental cost onto society. This highlights how, without strong policy guardrails, market forces alone cannot be relied upon to drive decarbonization at the necessary pace and scale.

In essence, the climate crisis exposes a fundamental flaw in our current socio-economic structure: a systemic inability to prioritize long-term collective well-being over immediate, concentrated gains. The "battle" against climate change has been lost not primarily due to technological limitations, but because the dominant systems of power and decision-making are inherently biased towards the short term, making the necessary long-term investments and transformations seem perpetually out of reach or politically infeasible. Addressing the climate crisis effectively, therefore, requires a fundamental challenge to this paradigm of profit maximization.

The Cost of Inaction

The deliberate retreat from climate commitments by corporations, governments, and financial institutions is not merely a political or economic phenomenon; it carries a profound and potentially irreversible environmental cost. Each weakened target, delayed policy, approved drilling permit, and withdrawn investment translates into additional greenhouse gases pumped into the atmosphere, pushing the global climate system further away from stability and closer to catastrophic tipping points. Quantifying the precise impact of each individual decision is complex, but authoritative scientific bodies provide a clear and alarming picture of the collective trajectory we are on, a path dictated by current policies and the very rollbacks documented in this report, and the devastating consequences that await if this course is not drastically altered.

The Widening Emissions Gap

The scientific consensus, spearheaded by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and corroborated by analyses like the UN Environment Programme's (UNEP) Emissions Gap Report and Climate Action Tracker (CAT), is unequivocal: the world will not meet the goals of the Paris Agreement. Based on the climate policies currently in place and the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) submitted by countries, commitments already being undermined by the reversals discussed , global emissions are projected to lead to devastating levels of warming this century.

The UNEP Emissions Gap Report 2024 starkly warns that a failure to significantly decrease greenhouse gas emissions in the next round of NDCs (due in 2025) will lock the world into a trajectory leading to a global average temperature increase of 2.6°C to 3.1°C above pre-industrial levels by 2100 (UNEP EGR 2024 Summary). These projections stand in stark contrast to the Paris Agreement's aim to limit warming preferably to 1.5°C, which we are already periodically surpassing.

To have a fighting chance of limiting warming below 2.0°C, the science demands immediate, rapid, and deep emissions reductions. The IPCC's Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) concluded that global greenhouse gas emissions must peak before 2025 and be slashed by 43% by 2030 compared to 2019 levels. UNEP's 2024 report echoes this urgency, calling for global cuts of 42% by 2030 and 57% by 2035 relative to current projections to align with limiting warming below 2.0°C. Yet, the reality painted by current policies is one of continued high, or even increasing, emissions in the near term. The 2023 Emissions Gap Report noted that policies in place at that time projected a 16% increase in global emissions by 2030 compared to levels when the Paris Agreement was adopted.

The gap between where we are headed and where we need to be is growing, directly fueled by the actions of establishment institutions. The decisions by Shell and BP to weaken targets and boost fossil fuel investment, the UK's delay of its petrol car ban, the US EPA's move to reconsider power plant regulations, the continued high rate of US drilling approvals (with permits issued in 2021-2022 alone estimated to cause over 800 million additional tons of GHG pollution), the withdrawal of banks from climate alliances, and the market-driven resurgence of coal all contribute directly to widening this emissions gap. They lock in fossil fuel infrastructure, delay the transition, and make the already Herculean task of achieving necessary emissions cuts exponentially harder.

European Greenhouse Gas Reduction Plans Are Stalling

The European Union are the world leaders in demonstrating that economic progress can still be maintained while reducing greenhouse gas emissions, seemingly bucking the global trend of backsliding on climate commitments. Recent data from the European Environment Agency indicates a significant 8% drop in net GHG emissions in 2023 compared to 2022, the largest annual decrease recorded. This continues a longer-term trend where EU emissions fell by roughly 35% between 1990 and 2023, even as the bloc's GDP grew substantially over the same period. Much of the recent success is attributed to the energy sector, which saw emissions plunge by around 18% in 2023 due to shifts towards renewable energy sources and reduced demand linked to energy prices. This progress is underpinned by a comprehensive legislative framework, notably the "Fit for 55" package, designed to align EU policies with its target of reducing emissions by at least 55% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels.

However, despite these positive headline figures and robust policy architecture, the EU's ability to maintain this momentum faces significant internal and external challenges, reflecting a more subtle form of potential backsliding driven by political and economic pressures rather than outright policy reversals. Implementing the ambitious "Fit for 55" package across 27 member states presents considerable hurdles, with legislative uncertainties creating potential avenues for legal challenges that will likely delay and weaken action. Furthermore, the transition is occurring against a backdrop of economic strain, including the cost of living crisis and high energy prices exacerbated by geopolitical instability. This has fueled a political backlash, often termed "Green Deal fatigue," where concerns about the costs and distributional impacts of climate policies risk eroding public and political support.

Far-right parties have deftly exploited this mounting discontent, eroding the resolve for ambitious climate action within both the European Parliament and individual member states. As the EU grapples with competing demands such as security, economic competitiveness, and energy affordability, securing the immense investments necessary for the successful implementation of the "Fit for 55" initiative grows increasingly unlikely. While the substantial reductions in greenhouse gas emissions over the past decade reaffirm Europe's global leadership and longstanding commitment to environmental stewardship, emerging economic and political pressures now threaten to overshadow previous achievements, placing the EU's future climate commitments and aspirations for a sustainable future in serious jeopardy.

The Qualitative Cost Beyond Degrees Celsius

A global average warming of 2.7°C or potentially over 3°C is not merely a number; it represents a fundamentally different planet, one plagued by widespread and severe impacts far exceeding those already being experienced at around 1.2°C of warming. The IPCC reports provide sobering detail on the qualitative differences between warming scenarios. The risks of species extinction escalate dramatically with each increment of warming. Coral reefs, vital marine nurseries, face near-total annihilation above 2°C. Terrestrial ecosystems will face unprecedented stress, leading to widespread biodiversity loss and potential ecosystem collapse (e.g., large-scale forest dieback).

Warming beyond 2°C above pre-industrial levels is projected to commit the planet to substantial sea level rise over the coming centuries, with profound implications for coastal communities, infrastructure, freshwater resources, and entire ecosystems. With 2°C of warming, global mean sea level is projected to rise between 0.46 and 0.99 meters (1.5 to 3.25 feet) compared to 1986–2005 levels. Under a 3°C warming scenario, projections indicate a 1.3 to 1.6 meters (4.3 to 5.2 feet) by 2100. Estimates suggest a rise of approximately 2 to 3 meters (6.6 to 9.8 feet), by 2150 with 3°C warming.

The primary drivers of this projected sea level rise include the thermal expansion of seawater as it warms and the melting of glaciers and ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica. Recent studies have identified potential tipping points, such as the intrusion of warmer seawater beneath Antarctic ice sheets, which could accelerate ice loss and contribute to higher sea levels than models have previously anticipated.

Compared to 1.5°C, warming approaching 3°C will bring significantly more frequent and intense heatwaves, heavier rainfall events leading to frequent severe flooding, longer and more damaging droughts in many regions, and stronger tropical cyclones.

Higher temperatures, increased water scarcity in many agricultural regions, and more frequent extreme weather events will severely disrupt food production, leading to increased risks of food shortages, price volatility, and malnutrition, particularly in vulnerable regions.

Increased heat stress will lead to higher rates of heat-related illness and death. Changing climate patterns will expand the range of vector-borne diseases like malaria and dengue fever. Air quality is likely to worsen in many areas.

Perhaps most alarmingly, higher levels of warming significantly increase the risk of crossing critical thresholds in the Earth's climate system. These include the irreversible collapse of major ice sheets (Greenland and West Antarctic), abrupt thawing of permafrost releasing vast amounts of stored carbon, disruption of major ocean currents, and large-scale dieback of forests like the Amazon. Crossing such tipping points could trigger runaway warming and lead to abrupt, irreversible changes on timescales that will make it difficult to maintain human civilization.

Projected CO2 Levels:

Based on the most recent data from NOAA's Global Monitoring Laboratory, the global average atmospheric CO2 concentration reached 426.03 ppm in January 2025, indicating an increasing rather than a decreasing rate of emissions over the decade. This marks a significant increase from pre-industrial levels, which were approximately 280 ppm, representing a rise of over 50% in less than 200 years. If this recent annual growth rate continues unabated, a likely scenario given the documented retreat from climate commitments, atmospheric CO2 levels would increase by approximately 38 ppm over the next decade. This trajectory suggests that by early 2035, the global average atmospheric CO2 concentration could reach approximately 464 ppm, a staggering 164 percent increase over two centuries.

Since Homo Sapiens have walked the earth atmospheric CO₂ concentrations fluctuated between 180 and 280 ppm over the past 300,000 years, driven by natural processes such as volcanic activity, oceanic absorption, and variations in Earth's orbit. Mankind and the ecological system that maintains us were not evolved to prosper in such a rich greenhouse gas environment. This relentless rise underscores the direct consequence of failing to curb emissions, pushing the climate system that sustains us further into uncharted and dangerous territory.

A Calculated Path to Catastrophe

The documented retreat from climate commitments by powerful established interests is, therefore, not just a failure of leadership or a betrayal of public trust; it is an active choice with quantifiable and devastating consequences. By prioritizing short-term profits and political convenience, these actors are consciously steering the world away from the relatively manageable risks of 1.5°C warming towards a future defined by the catastrophic impacts associated with warming approaching 3°C (with some of the latest climate models projecting increases up to 5°C). The price of this inaction, measured in human lives, economic disruption, and ecological collapse, is incalculable, yet the decisions driving us towards it continue unabated.

Economic Growth vs. Climate Stability

At the heart of our failure to reduce greenhouse gas emissions lies a fundamental tension between economic growth and climate stability. For most of industrial history, these two goals have been in direct conflict. Economic expansion has been powered by fossil fuels, with GDP growth tightly coupled to increased energy consumption and carbon emissions. This relationship has been so consistent that economists and energy analysts long considered it an immutable law: to grow an economy, one must increase emissions.

Historically, CO2 emissions have been strongly correlated with economic development, particularly in low-to-middle income countries. As nations industrialized, their carbon footprints expanded in lockstep with their GDPs. This pattern held true across different political systems, cultural contexts, and time periods. The underlying mechanism was straightforward: economic growth required more energy; energy came primarily from fossil fuels; burning fossil fuels released carbon dioxide. The result was a seemingly unbreakable link between prosperity and pollution.

In recent decades, however, a more nuanced picture has emerged. Many developed economies have achieved what economists call "decoupling"—continuing to grow their GDPs while reducing their carbon emissions. The United Kingdom provides a striking example. Since 1990, the UK's GDP has increased substantially while its emissions have fallen by approximately 40%. Similar patterns can be observed in France, Germany, Sweden, Finland, Denmark, Italy, and other high-income nations. The United States has also shown signs of decoupling, with a 32% increase in GDP between 2005 and 2021 accompanied by a 17% decrease in CO2 emissions.

This decoupling is not merely an accounting trick achieved by offshoring carbon-intensive industries to developing nations. Studies that account for consumption-based emissions—which include the carbon footprint of imported goods—still show decoupling in many advanced economies. While some emissions have indeed been exported overseas, this is not the sole driver of the observed reductions. Two key factors have enabled this partial decoupling: improvements in energy efficiency that allow economies to produce more value with less energy, and the transition from fossil fuels to low-carbon energy sources like wind, solar, and nuclear power.

Yet this encouraging trend in some wealthy nations must be placed in global context. Worldwide, emissions continue to rise because decoupling in developed economies has been more than offset by increased emissions in rapidly industrializing nations. China, India, and other emerging economies are following carbon-intensive development paths similar to those previously taken by Western countries. While their per-capita emissions often remain far below those of the United States and other wealthy nations, their large populations and rapid growth rates make them major contributors to global emissions.

Moreover, even in countries that have achieved some decoupling, the pace of emissions reduction falls far short of what climate science tells us is necessary. The critical question is not whether decoupling is possible, it clearly is, but whether it can happen quickly enough and broadly enough to prevent catastrophic warming. Current evidence suggests it cannot, at least not without far more aggressive policies than those currently in place.

This brings us to the fundamental challenge of our time: reconciling the legitimate development aspirations of billions of people with the physical constraints of our atmosphere. Economic growth remains essential for addressing poverty, improving health outcomes, and meeting basic human needs. Indeed, 13 of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals are directly linked to economic and social development. Yet traditional carbon-intensive growth pathways are no longer viable if we wish to maintain a stable climate.

The tension between growth and sustainability has led some scholars to advocate for "degrowth" or steady-state economic models in wealthy nations. Others maintain that technological innovation, particularly in clean energy, can enable continued growth without environmental destruction. What is clear is that our current economic paradigm—with its emphasis on ever-increasing consumption, planned obsolescence, and fossil fuel subsidies—is incompatible with climate stability.

The relationship between economic growth and emissions thus presents us with difficult choices. We can continue prioritizing short-term economic expansion at the expense of the climate. Or we can pursue more aggressive decoupling through massive investments in clean energy, efficiency, and circular economy principles. Or we can reimagine economic success itself, moving beyond GDP as the primary metric of progress to include measures of wellbeing, sustainability, and equity.

What we cannot do is continue pretending that minor adjustments to business-as-usual will be sufficient. The physics of climate change does not negotiate, and the carbon budget for limiting warming to relatively safe levels is nearly depleted. The economic transformation required to address climate change while meeting human needs is unprecedented in scale and urgency. It demands new economic thinking, new metrics of success, and new forms of international cooperation.

Fifty years ago, climate scientists armed with rudimentary computers and limited data made a remarkable prediction: human greenhouse gas emissions would significantly warm the planet. Today, we know they were right. The climate models of the 1970s, despite their simplicity by modern standards, accurately projected the warming trajectory we have experienced. Modern models, with their vastly increased sophistication and precision, have only confirmed and refined these early insights. The fundamental physics of climate change has been well understood over a century and precisely calculated for over 50 years.

Yet throughout this same period, our collective response to this knowledge has been woefully inadequate. Global greenhouse gas emissions have not decreased—they have more than doubled. The 2020s are on track to be the warmest decade in recorded history. We have squandered fifty years of foreknowledge, choosing short-term economic growth and consumption over long-term climate stability.

This failure cannot be attributed to scientific uncertainty or technological limitations. The warnings from climate scientists have been consistent and increasingly urgent. The technologies needed to begin decarbonizing our economies, renewable energy, energy storage, electric vehicles, heat pumps, have become increasingly affordable and effective. Some developed economies have demonstrated that economic growth can be decoupled from emissions, proving that prosperity need not come at the expense of the climate. What has been lacking is not knowledge or tools, but political will and economic transformation at the necessary scale and speed.

The carbon budget for limiting warming to relatively safe levels is rapidly depleting. At current emission rates, the budget for 2.5-3.0°C, a level of warming that will still cause significant harm to human and natural systems, will be consumed within about 25 years if emissions continue unabated. The window for gradual, comfortable transitions has closed. We now face the prospect of either rapid, disruptive decarbonization which established institutions have rejected or devastating levels of warming. We will not find a middle ground by collectively sticking our heads in the sand.

Winning the War

We’ve painted a grim picture. A world where the institutions most capable of steering humanity away from climate catastrophe – powerful corporations, national governments, and the global financial system – are actively retreating from their responsibilities. Entrenched interests, the allure of short-term profits, and political expediency have demonstrably overridden scientific warnings and public appeals, leading to weakened commitments, policy reversals, and continued investment in the fossil fuels driving the crisis. We have, by the metrics of institutional action and near-term emissions trajectories, lost the battle to keep warming safely below dangerous thresholds through conventional means.

Acknowledging this failure, however, does not necessitate despair. Instead, it demands a shift in focus towards strategies that operate outside, alongside, and often in opposition to these failing established powers. If the war for a habitable planet is to be won, it will likely be through shifting the story away from anxiety inducing calamity to the rewards of living in a sustainable civilization; by building resilience forged by personal adaptation; by gaining a neutral third-party perspective from AI to help guide us through the challenges ahead; and to channel the disruptive power wielded by social movements.

Why the Climate Story Must be Reframed

The widespread phenomenon of climate anxiety among young people places an immediate and profound responsibility upon the environmental movement. Far from being a marginal concern, this anxiety has become a deeply embedded emotional reality for youth around the world. If the movement's messaging, though scientifically sound and earnestly conveyed, exacerbates anxiety, leading young individuals to retreat in search of emotional comfort rather than rallying them toward collective action, then it signifies a fundamental failure. Achieving the sustained, long-term reductions in emissions necessary for our planet’s future depends entirely on the active participation and committed engagement of the next generation. Thus, confronting and alleviating youth climate anxiety is not merely an auxiliary task aimed at emotional support; rather, it is an indispensable first step toward prevailing in the broader cultural and political struggle against entrenched institutions driving the climate crisis.

Large-scale studies, such as the 2021 survey published in The Lancet Planetary Health covering 10,000 youth in 10 countries, paint a stark picture: 59% reported being very or extremely worried about climate change, 84% were at least moderately worried, and a staggering 75% described the future as "frightening." More than 45% stated that their feelings about climate change negatively affected their daily life and functioning. This profound distress, sometimes termed eco-anxiety, stems from witnessing the escalating impacts of climate change, coupled with a perception of inadequate action from governments and older generations, leading to feelings of fear, helplessness, anger, and betrayal.

A narrative focused solely on catastrophe risks fostering paralysis and despair, undermining the very mobilization needed. Therefore, the environmental movement must strategically reframe its story, balancing the necessary alarm with a tangible, uplifting vision, emphasizing human agency, and showcasing a viable path forward. By validating young people's fears while actively cultivating pathways for empowerment, collective action, and a vision of a beautiful, sustainable future, the movement can begin to heal the anxiety it may inadvertently exacerbate. This shift is not about diluting the message, but about building the resilient, hopeful, and broad-based coalition necessary to challenge entrenched power and achieve transformative change.

Where to Begin Our Story

Despite the remarkable analytical tools at our disposal, driven by logic and technological prowess, there remain deeper, timeless sources of wisdom essential to fortify the foundation beneath climate activism. Listening thoughtfully, to ourselves and to nature, is a profound act, one that reconnects us intimately with the very essence of our humanity. Our emergence as sentient beings was gently cradled by Mother Earth, a truth richly woven into the fabric of cultural, spiritual, and philosophical traditions across civilizations. Though expressed in diverse voices, these varied traditions unite in a common summons: that humanity must pause, listen with intention, and realign itself harmoniously with the timeless rhythms and deep wisdom of the Earth, if we are to truly honor our inheritance and move toward a sustainable future.

In Christianity, reverence for the earth is embedded within scripture itself. Psalm 19 poetically declares, "The heavens declare the glory of God; the skies proclaim the work of his hands," urging us to perceive divine wisdom through the natural world. Similarly, St. Francis of Assisi, celebrated as the patron saint of ecology, advocated for deep humility and kinship with nature. His Canticle of the Creatures famously praises elements of nature as brother and sister, encouraging us to embrace the earth as family rather than resource, to listen humbly, and recognize our interdependence with all living things.

Leading American philosophers like Thoreau embody the spirit of listening deeply to nature through his seminal work, Walden. Retreating into the simplicity of the woods, Thoreau sought clarity, wisdom, and spiritual rejuvenation by immersing himself in nature’s silent teachings. He famously writes, “I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life.” Thoreau’s approach emphasizes the value of quiet observation and introspection, teaching that by listening to the natural world, we become more fully alive, more aware, and more authentically ourselves.

Eastern traditions sound a similar call. The ancient wisdom of Lao Tzu in the Tao Te Ching is fundamentally rooted in harmony with nature. Lao Tzu instructs us: "Nature does not hurry, yet everything is accomplished." He teaches the Tao, or "the Way," encouraging us to align our lives with nature’s effortless balance. By listening and following nature's example, we find serenity, authenticity, and the proper rhythm of life. The Taoist philosophy continuously guides us back to nature as a model of simplicity, patience, and peace.

The teachings of Buddha often invoke nature as a source of profound insight into the impermanence, interconnectedness, and ultimate unity of existence. Buddha emphasized the significance of nature as a profound space for awakening. The Buddha taught mindfulness, instructing his followers to observe the natural world closely, seeing it as it truly is, as a reflection of universal truths about suffering, impermanence, and the path to liberation. The Dhammapada reminds us: "As a bee gathering nectar does not harm or disturb the color and fragrance of the flower, so do the wise move through the world." Such teachings direct us to listen carefully to nature’s lessons, embracing gentle interaction rather than domination.

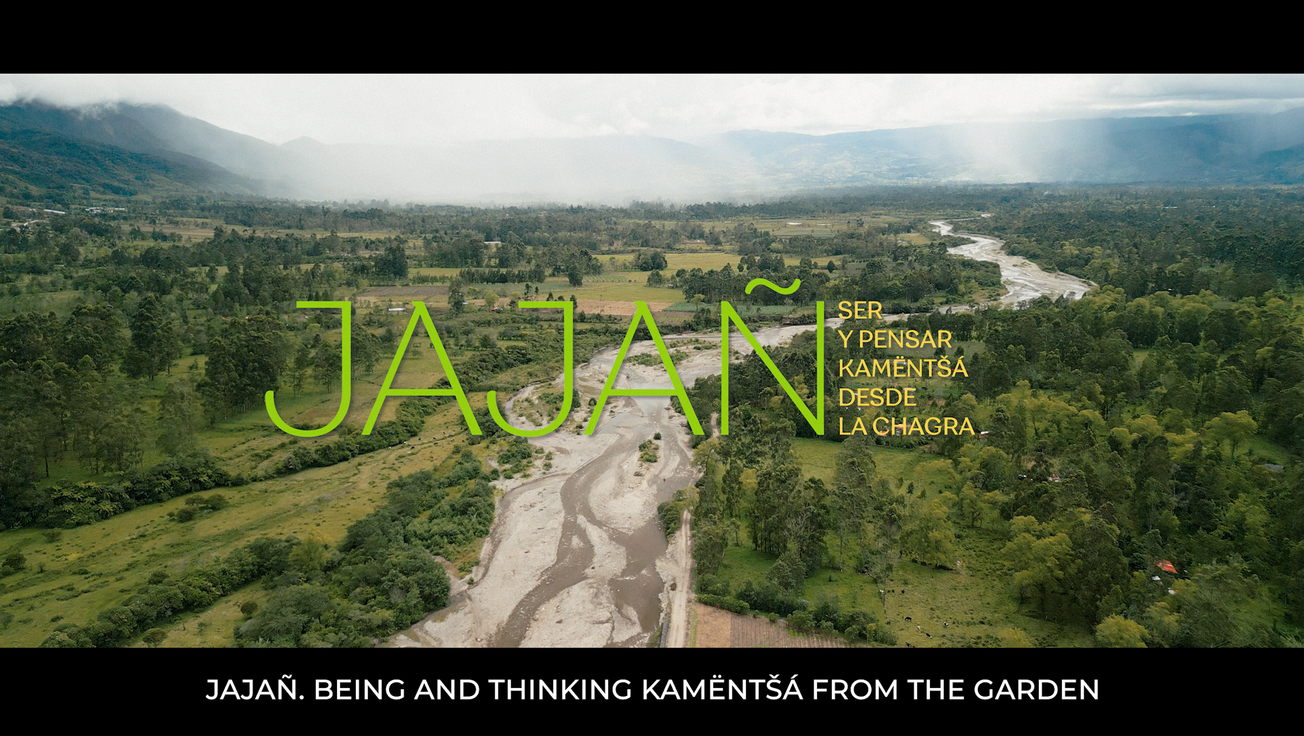

Indigenous cultures around the world offer particularly powerful examples of listening deeply to Mother Earth. Indigenous teachings emphasize reciprocity, harmony, and respect toward all elements of the natural world. They see themselves as custodians, not conquerors, of the earth. For example, Native American spiritual traditions often describe the earth as a living, nurturing mother who communicates wisdom and guidance. Chief Seattle famously expressed, “Whatever befalls the earth, befalls the sons and daughters of the earth,” a profound reminder that our fate is tied directly to the well-being of the earth itself.

The guidance from these diverse spiritual and philosophical traditions underscores a vital, universal truth: humanity’s well-being and wisdom depend on our willingness to listen, to ourselves, to nature, and to the deeper currents of existence. By heeding these ancient and timeless voices, whether through the poetic reflections of Thoreau, the contemplative quietness of Buddha, the harmonious teachings of Lao Tzu, the reverence of Christianity, or the sacred stewardship exemplified by Indigenous peoples, we are invited to rediscover a profound sense of belonging, duty, and interconnectedness with the Earth that nurtured our emergence as conscious beings. It is through embracing these timeless voices that we find the clarity, resilience, and courage essential to confronting and transforming the established order.

Our Shared Path Through the Climate Crisis

Our planet, a vibrant tapestry woven with interconnected ecosystems and diverse human cultures, faces challenges that transcend borders and demand unified action. The familiar adage "Think Globally, Act Locally" resonates with particular urgency today. Earth functions as a single, integrated environmental system; the atmosphere knows no national boundaries, and the consequences of environmental degradation ripple across continents, affecting us all.

Yet, in the face of this shared threat, a countercurrent persists: an overemphasis on nationalism and patriotic fervor that risks fragmenting our collective will and weakening our ability to cooperate effectively. Addressing the profound environmental challenges before us requires a fundamental shift in perspective – recognizing our shared humanity, celebrating the collective achievements of humankind regardless of nationality, and embracing the wisdom found across cultures and traditions. By acknowledging that we are one people inhabiting one Earth, we can begin to forge the global solidarity necessary to not only confront the climate crisis but also to ensure a just and sustainable sharing of our planet's bounty for generations to come.

The urgency for global thinking is starkly illustrated by the nature of climate change itself. Our planet operates not as a collection of isolated nations but as a deeply interconnected system of systems – the atmosphere, oceans, land, and ice are inextricably linked, constantly exchanging energy and matter. Greenhouse gas emissions released in one part of the world do not remain confined; they disperse globally, contributing to rising temperatures, altered weather patterns, sea-level rise, and ocean acidification that impact communities thousands of miles away. The melting of polar ice caps affects coastal regions worldwide, changes in ocean currents influence weather patterns across continents, and deforestation in one region can impact rainfall in another. As organizations like the United Nations Development Programme emphasize, climate change is intertwined with other global crises like biodiversity loss and pollution, creating complex challenges that demand integrated, worldwide solutions. Attempting to address such a fundamentally global phenomenon through purely national lenses is akin to trying to bail out a sinking ship with a sieve; the scale of the problem necessitates a coordinated, global response that recognizes our shared vulnerability and responsibility within this single, indivisible Earth system.

Despite the clear global nature of the climate crisis, the pervasive influence of nationalism presents a significant obstacle to effective collective action. Nationalism, by its very definition, emphasizes the primacy of the nation-state, often prioritizing perceived national interests over shared global concerns. This inherent tribal, boundary-building characteristic clashes fundamentally with the borderless nature of climate change, which demands cooperation and the dissolution of barriers.

In practice, this manifests as governments hesitating to commit to ambitious climate targets or policies that might impose short-term economic costs or require significant international resource transfers, fearing a loss of competitive advantage or sovereignty. The rise of "climate nationalism" sees nations framing decarbonization efforts primarily through a lens of national economic gain or security, fragmenting global markets and undermining multilateral efforts like the COP summits. Furthermore, nationalist narratives are being exploited for political gain to shift blame for inaction onto other countries, hindering both domestic policy and international negotiations. By fostering an "us vs. them" mentality, nationalism erodes the trust and solidarity essential for tackling a shared existential threat, weakening our collective capacity to implement the far-reaching, cooperative solutions that climate science tells us are necessary.

The narrative of nationalism often obscures a fundamental truth: human progress itself is a testament to global collaboration and shared ingenuity, not the isolated triumph of any single nation. The very foundations of modern civilization are built upon discoveries and innovations originating from diverse cultures across the world, exchanged and built upon over centuries.

Consider the mathematical language we use daily: the indispensable concept of zero and the elegant decimal place-value system trace their roots back to ancient India. From ancient China came transformative technologies like papermaking and printing, which revolutionized the dissemination of knowledge, alongside the compass that guided explorers across oceans and gunpowder that reshaped global power dynamics. During its Golden Age, the Islamic world served as a crucial bridge, preserving and significantly advancing Greek knowledge while making groundbreaking contributions in algebra, medicine, astronomy, and optics. And the philosophical inquiries, democratic ideals, and systematic approaches to geometry and logic pioneered in ancient Greece continue to underpin Western thought and scientific methodology. These examples, merely a fraction of the foundations that built every modern nation, illustrate that the achievements of any one society are ultimately achievements for all humankind.

The nationalist belief that a country inherently deserves greater material wealth solely by virtue of its ingenuity and labor is not only disconnected from reality, but stands as a profound impediment to addressing today's global challenges. America's current hyper-nationalist leadership is exacerbating global divisions, fostering an environment in which belligerency is rewarded, allowing nations to seize Earth's resources behind walls of trade barriers and fervent nationalism. Such attitudes inevitably breed similar sentiments elsewhere, creating a cascading cycle of competitive isolationism. This destructive ideology must be vigorously confronted from all angles, for it leads only to a dead end, obstructing the collaborative spirit essential to achieving effective and sustainable climate solutions.

The path forward requires a conscious shift away from the narrow confines of nationalism towards a broader embrace of our shared humanity and collective destiny. The interconnected nature of our planet, particularly evident in the climate crisis, leaves us no other choice. While local actions remain crucial, they must be undertaken within a framework of global awareness and coordinated strategy. Celebrating the diverse contributions of all cultures to human progress and heeding the calls for unity and compassion echoed in our spiritual traditions can fortify our resolve to work together. Let us choose cooperation over competition, solidarity over isolation, and shared responsibility over narrow self-interest. By thinking globally, acting collaboratively, and pursuing the equitable sharing of Earth's resources, we can confront the environmental challenges ahead and build a more just, peaceful, and sustainable future for all humankind.

AI, Civic Participation, and Climate Activism

Ultimately to win the climate war, we need to make room for the climate story in our daily lives. Maintaining one's personal life often demands the lion’s share of our time, energy, and attention, leaving precious little space for meaningful engagement in community initiatives, activism, or global concerns. Yet, could AI and automation become the keys to significantly reducing working hours and revitalizing civic life, including crucial climate activism? Sociological research has consistently highlighted a strong correlation between available free time and community participation. In his influential study, Bowling Alone, sociologist Robert Putnam observed that the most frequently cited reason for withdrawal from community engagement is being "too busy" due to work obligations. It is not apathy but a relentless scarcity of time that frequently prevents individuals from volunteering or participating in community dialogue. Conversely, when afforded greater discretionary time, people naturally become more inclined to volunteer, join grassroots efforts, and actively contribute to civic life.

This was intuitively understood by earlier generations, the push for the two-day weekend was partly so workers could spend Saturdays on civic, family, and leisure pursuits. Tellingly, some early 20th-century business leaders opposed shorter hours precisely because they feared “idleness breeds mischief, even worse, radicalism,” worrying that workers with time on their hands would agitate for change. Modern data backs up these intuitions: surveys consistently find that long working hours correlate with lower rates of volunteering and civic engagement, whereas societies with more generous vacation and work-hour policies often report higher social capital and community participation.

Throughout modern history, technological progress has often led to shorter average work hours, as societies opted to take some gains in the form of leisure. Research points out that many past productivity improvements translated into reduced working time. For instance, in the mid-20th century Western European countries steadily reduced working hours (through shorter workweeks and longer vacations), whereas the United States did not. By 2005, Europeans were working roughly 50 percent fewer hours per person than Americans. Europeans chose more free time over working longer primarily because leisure and civic life is institutionally supported, culturally valued, and politically protected. These collective choices reflect deeper societal beliefs in quality of life, social equality, communal participation, and sustainable living, rather than purely maximizing income and consumption.

Because of their cultural and political approach to life, Europeans are global leaders in progressive climate change programs. Europeans have long valued leisure and work-life balance as integral to personal and societal well-being. Historical traditions rooted in communal values, family orientation, and cultural enrichment contributed significantly. Europeans traditionally view leisure not merely as relaxation, but as necessary for personal development, health, and civic participation. Countries like France, Italy, and Spain have cultural norms deeply embedded around shared meals, family time, and community life, making leisure a fundamental component of social identity rather than simply a luxury.

European countries widely adopted social-democratic economic models, prioritizing social cohesion, equality, and quality of life over relentless economic growth. Generous welfare systems (universal healthcare, public pensions, unemployment benefits, paid family leave) reduced pressure on individuals to maximize earnings for personal security, enabling more people to choose leisure and community involvement rather than constant work. European policies emphasized equitable income distribution, which decreased pressure to earn more simply to keep up with consumption norms. Thus, Europeans have historically prioritized social well-being rather than accumulating individual wealth through longer work hours.