The Consequences of False Narratives for Global Climate Stability

In recent years, an increasing number of influential voices have raised alarms that declining birth rates and shrinking populations represent an existential risk to humanity. Prominent among these is Tesla CEO Elon Musk, who has frequently characterized "population collapse" as the "greatest threat to civilization," going so far as to assert that it poses an even more severe risk than climate change. Whether motivated by genuine concern, strategic diversion, or other factors, such claims have significantly influenced public discourse on demographic trends and societal priorities. U.S. President Donald Trump has likewise lamented declining births, declaring on the campaign trail, “We want more babies… I want a baby boom.” China’s President Xi Jinping has explicitly put the issue on the national agenda, vowing “a policy system to boost birth rates” in response to China’s aging population and demographic downturn. These statements reflect a stark shift in rhetoric: after decades of concern about ‘overpopulation’, many world leaders are now sounding alarms about ‘underpopulation.’

This new narrative falsely argues that low fertility and shrinking populations will undermine human progress. As Musk warns, “If these trends continue, humanity will cease to exist.” Such hyperbole is catching on. Policymakers in several countries are openly fretting about “baby busts” and devising plans to spur a new baby boom. It’s a discourse that spans ideological lines – from nationalists worried about cultural survival to technocrats worried about GDP growth. However, a closer look reveals that the panic over declining birth rates is misguided, steeped in bias, environmentally dangerous and blind to humanity’s growing technological capacities. Let’s try to unpack the key motivations behind underpopulation fears and present a fact-based challenge to this emerging panic.

What’s Driving this Fear? Three Key Motivations

Cultural and Identity Preservation: For many, concerns about low birth rates are entangled with questions of cultural or ethnic survival. In countries or communities where the native-born population is stagnant or falling, leaders worry that “our people” will be outnumbered or “replaced” by others. This motivation is evident in pronatalist rhetoric that explicitly ties reproduction to national or ethnic identity. For example, Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has bluntly stated, “We want Hungarian children. Migration for us is surrender.” His government offers loans and tax breaks to Hungarian women who have multiple children, aiming to boost the ethnic Hungarian birth rate while rejecting immigration.

Demographers note that if ‘native born’ American birth rates remain low, future population growth will depend almost entirely on immigration. That reality triggered intense political conflict in the U.S., as seen in Trump’s speeches linking certain demographics to national greatness, and certainly helped reelect him. Trump’s own pronatalist language calling for a ‘new baby boom’ is intertwined with a vision of ‘national renewal’ and strength.

In January 2025, President Trump signed an executive order aimed at eliminating automatic citizenship for children born in the United States to undocumented immigrants, a move aligned with longstanding goals expressed during his administration. Although Trump has avoided explicitly stating a preference for increasing births specifically among people of white European descent, several of his administration's actions and statements collectively suggest a strong preference for bolstering America's native-born population, particularly among groups of European heritage. For instance, his administration's restrictive immigration policies notably favored immigrants from European nations, including advocating for increased immigration from countries like Norway, while explicitly disparaging immigrants from Africa and Latin America. Additionally, Trump administration officials frequently invoke themes related to preserving Western culture and European heritage, exemplified by senior advisor Stephen Miller’s advocacy for policies aimed at protecting the demographic dominance of white Americans. Taken together, these policies and rhetoric implicitly emphasize preserving European lineage and cultural dominance, reflecting a clear underlying demographic preference.

In extreme forms, this veers into the racist ‘Great Replacement’ conspiracy theory, the false notion that white or Christian populations in the West are being supplanted by non-white, immigrant populations. A May 2022 Yahoo News/YouGov poll found that 61 percent of individuals who voted for Donald Trump in the 2020 U.S. presidential election agreed with the statement that "a group of people in this country are trying to replace native-born Americans with immigrants and people of color who share their political views." Similarly, a Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) survey conducted in April 2022 revealed that nearly 7 in 10 Republicans surveyed concurred, to varying degrees, with the belief that demographic changes in the United States are deliberately orchestrated by liberal and progressive politicians and global elites to gain political power by "replacing more conservative white voters." This completely unfounded theory exploits anxieties surrounding immigration, declining birth rates among white populations, and perceived threats to cultural cohesion, often using inflammatory and racist rhetoric to galvanize a conservative political base in America.

Similar sentiments echo in other nations as well: a recent analysis found that at least 30 percent of countries now have pronatalist policies (up from just 10 percent in the 1970s) as leaders want to utilize women’s bodies to serve nationalistic, economic and patriarchal interests. Such fears, while couched as concern for what they perceive as ‘civilization,’ reveal a deeply-felt desire to preserve a particular tribe’s dominance and cultural norms over others. Calls for more babies are not referring to the booming populations of Africa (which will become the world’s most populous continent with 3.8 billion people by 2100) or South Asia; they usually mean more babies ‘of one’s own group.’ This tribal subtext is a powerful driver of the underpopulation narrative.

Economic Anxiety and Aging Populations: Another significant motivation cited for increasing birthrates stems from reliance on outdated economic models that equate declining fertility rates directly with diminished economic growth potential. Policymakers operating under these traditional frameworks warn that shrinking working-age populations combined with rising numbers of elderly citizens will inevitably destabilize economies. They argue that fewer younger workers lead to labor shortages, lower productivity, and strained pension and healthcare systems as the available tax base shrinks. For example, the U.S. fertility rate of approximately 1.62 births per woman, well below the conventional "replacement level" of 2.1, is often presented as a precursor to economic decline and demographic imbalance. Japan is frequently cited as a cautionary example, experiencing one of the lowest birth rates globally, with annual births recently falling below 800,000 causing an overall declining population.

However, these concerns reflect a rigid adherence to obsolete economic paradigms that do not fully account for innovation, automation, and evolving societal structures. Contemporary economies will increasingly rely on productivity gains driven by technological advancements, such as artificial intelligence, robotics, and improved healthcare, that can substantially offset the economic effects of lower birthrates. Rather than directly leading to reduced economic growth, lower fertility rates can catalyze economies to innovate, encouraging investments in human capital, extended workforce participation, and technological infrastructure. Thus, demographic shifts need not imply economic decline, provided societies adapt thoughtfully to the opportunities inherent in these changing population dynamics.

In China, President Xi Jinping has publicly expressed deep concern about an ‘imminent’ demographic decline, warning that shrinking population numbers could weaken economic dynamism and impede national progress. These apprehensions have legitimate roots: an aging society typically brings with it reduced consumer spending, fewer innovators, and the potential to stall economic growth. Nevertheless, as we shall examine, viable policy frameworks and emerging technologies offer effective pathways to successfully navigate the challenges posed by an aging population. Continuous population expansion is neither the sole route to sustained economic prosperity nor a viable strategy, as unchecked demographic growth will most certainly exacerbate the severe risks of climate disruption.

Geopolitical and Military Strength: Population size has long been linked to national power. Leaders fret that a smaller population will diminish their country’s influence, military manpower, or geopolitical clout relative to rivals. This motivation is evident in the strategic framing of demographic decline as a security risk. For example, China’s leadership, while concerned economically, also sees maintaining a robust population as vital to sustaining its position as a global superpower. China’s population peaked in 2022 and has now begun to decline, raising alarms in Beijing about potential long-term weakening of national power.

In Russia, President Vladimir Putin has lamented population decline for years and introduced ‘Mother Heroine’ awards and cash incentives for large families, a patriotic appeal for Russians to have more children to strengthen the nation. Even in the United States, Trump’s own pronatalist language (‘new baby boom’) is intertwined with a vision of national ‘renewal’ and strength.

In short, throughout history national leaders have viewed population growth as an arms race: more people can mean a bigger economy, a bigger army, and a bigger say on the world stage. This geopolitical lens helps explain why countries like Turkey, Iran, Hungary, and Poland, often led by nationalist governments, have launched campaigns to boost birth rates. Falling numbers are seen as a threat to national survival in a competitive world.

Racial and Cultural Bias in the Population Debate

While concerns regarding the economic and social consequences of demographic changes are understandable, it is crucial to recognize that calls for higher birth rates most often reflect underlying racial and cultural biases. Contrary to alarmist narratives, the global population is not shrinking; rather, it continues to grow substantially and is projected to reach approximately 9.7 billion by mid-century. Even conservative fertility scenarios from the United Nations predict that the world’s population will exceed 10 billion by the year 2100. By nearly every measure, such a population size, combined with current consumption patterns, is unsustainable. Research consistently demonstrates that humanity is already exceeding planetary limits, consuming natural resources at a rate equivalent to 1.7 Earths annually. In other words, our current global consumption surpasses the planet’s regenerative capacity by nearly 70%, highlighting the urgent need to reconsider both population dynamics and consumption habits in the pursuit of ecological stability and sustainable human welfare.

It is vital to place these numbers in historical perspective. At the time of my grandmother’s birth, the global population stood at merely 1.36 billion. By my mother's generation, that figure had grown to 2.0 billion, and by the time of my own birth, it had reached approximately 2.3 billion. In a world with fewer than one-quarter of today's inhabitants, humanity could afford to overlook its ecological footprint and the strain placed on planetary resources. But at a population level nearing 10 billion, the consequences of human activity on Earth's natural systems become impossible to disregard or deny.

Most notably, population growth will not be evenly distributed: Africa is on track to be the epicenter of population increase. More than half of all global population growth between now and 2050 is expected to occur in Africa. For example, Nigeria’s population (around 220 million today) is projected to surpass that of the United States by 2050, making it the world’s third most populous country by century’s end. Africa’s population is set to double from ~1.3 billion now to ~2.6 billion by 2050, and could reach 4.0 billion by 2100. In other words, humanity is not at risk of extinction from declining populations, it’s undergoing a shift, with faster growth in some regions and decline in others.

Nevertheless, those sounding alarms about underpopulation rarely embrace the rapid demographic growth in regions like Africa and South Asia as a positive contribution to humanity’s collective future. Instead, their discourse often betrays a subtle anxiety that their own nations or cultural identities may shrink relative to the growth of others. Elon Musk, for example, notably dismissed immigration as a solution, rhetorically asking, "What about immigration? I'm like, from where?" Yet the evidence clearly contradicts such concerns: substantial portions of the world, including countries like Nigeria and India, will continue to experience population growth throughout this century. The unspoken unease for Musk and similarly minded commentators appears rooted less in a fear of declining global numbers and more in discomfort that this growth is taking place outside societies with which they personally identify.

Their narrative reveals a profound underlying bias: the prospect of an additional billion people in Africa and India does not alleviate their fears of a supposed "population collapse," because their concern implicitly centers around which populations are experiencing growth. As demographer Alistair Currie incisively notes, "The critical irony is that the very places where Musk bemoans the falling birth rate are those whose populations impose the greatest ecological footprint. Indeed, in high-consumption nations, lower birth rates result in fewer carbon emitters and reduced pressure on already strained global resources, a development that could significantly benefit global sustainability. Yet pronatalist rhetoric consistently ignores this reality, narrowly fixating instead on the declining numbers within affluent or majority-ethnic groups. It is vital to remember that no single group holds an inherent entitlement to Earth's finite resources and that populations identifying as white represent less than eight percent of humanity as a whole.

When politicians label women who choose to have fewer children as ‘unpatriotic,’ or invoke fears of demographic ‘replacement,’ they exploit ethnic insecurities rather than genuinely addressing human welfare. A truly constructive demographic policy would affirm the equal value of all people and pursue collaborative solution, such as managed migration and global development, rather than fueling divisive, zero-sum competition between ethnic groups. The global population is not dwindling; rather, it is shifting in composition. While century-long predictions inherently carry uncertainty, demographers nevertheless anticipate that humanity’s population a hundred years from now will be still be around 8 billion, roughly equivalent to today's numbers. Grasping this reality is essential for crafting policies that are both humane and effective.

Pronatalist Policies: Incentives, Coercion, and the Backlash on Women

In response to fears of population collapse, a wave of pronatalist policies has emerged, ranging from family incentives to outright coercive measures. Many of these efforts have profound implications for women’s rights and social progress. While encouraging childbearing is not inherently problematic, the methods matter. Unfortunately, several countries and political movements are embracing tactics that are regressive or even coercive in nature.

Financial ‘Baby Bonus’ and Rewards: Numerous governments are offering cash payments or tax breaks to parents for having children. For example, the U.S. is debating one-time payments of $5,000 per newborn while Hungary provides generous loans or lifetime tax exemptions to mothers who bear multiple children. Russia has offered ‘maternal capital’ grants to mothers of a second or third child, and Turkey and Iran have implemented monetary incentives as well. These incentives tie nationalist appeals to personal finance, effectively paying, or praising, citizens to fulfill a demographic duty. Hungary even instituted a ‘National Medal of Motherhood’ for women with 5+ children, harkening to earlier eras of state-awarded fertility medals. While such perks may encourage a few families, they also convey a general message that a woman’s highest service to the nation is producing babies.

President Trump has also advocated for measures to increase the U.S. birth rate, including the establishment of a "National Medal of Motherhood" for women who have six or more children. These initiatives have drawn comparisons to awards from authoritarian regimes, such as Nazi Germany's "Cross of Honour of the German Mother" and the Soviet Union's "Order of Maternal Glory." Such policies echoes similar refrains that a woman's highest service to the nation is through childbearing, rather than addressing broader systemic issues like affordable childcare and healthcare.

Vice President J.D. Vance has articulated a pronounced pronatalist stance, advocating for policies that prioritize traditional family structures and motherhood. In a 2021 interview, Vance proposed that Americans without children should pay higher taxes than those with children, stating, "If you are making $100,000, $400,000 a year and you've got three kids, you should pay a different, lower tax rate than if you are making the same amount of money and you don't have any kids. It's that simple"

Further emphasizing the political influence of parents, Vance suggested that parents should have more say in American democracy than non-parents. He proposed a system where parents could cast additional votes on behalf of their children, arguing that "children are not fairly represented in the democratic process." Vance has also been critical of women who prioritize careers over starting families. In a 2021 podcast, he remarked that professional women who choose careers over motherhood are on a ‘path to misery,’ suggesting that such choices lead to personal unhappiness. These statements reflect Vance's broader viewpoint that traditional family roles and increased birth rates are essential for societal well-being and the nation's future.

These modern pronatalist policies and statements echo past authoritarian practices that sought to control women's reproductive choices for nationalistic purposes. These approaches prioritize symbolic incentives over substantive support for families, such as paid parental leave, affordable childcare, and healthcare access. Framing motherhood as a patriotic obligation undermines women's autonomy and fails to address the structural challenges that influence reproductive decisions.

Propaganda for Traditional Gender Roles: Many pronatalist campaigns idealize a traditional family model with a home-making mother and breadwinning father. In the United States, recent proposals floated by conservative think-tanks included reserving elite scholarships (like Fulbright scholarships) only for married people with children, and even suggestions to teach teen girls ‘fertility awareness’ in lieu of comprehensive sex-ed. As one social commentator noted, these policies “seem intended to replicate only one form of family: a church-going stay-at-home mother, a breadwinning father, and…outdated gender roles.”

This ideological approach stigmatizes women who pursue careers or choose smaller families as somehow failing their duty. Indeed, researchers have found that in some right-wing nationalist circles, women who don’t have multiple children are labeled unpatriotic. Seyward Darby, in her book Sisters in Hate: American Women on the Front Lines of White Nationalism, discusses how far-right movements in the United States have historically emphasized traditional gender roles, portraying motherhood as a woman's highest calling and a duty to the nation. Women who deviate from this role by seeking careers or limiting family size are often viewed with suspicion or labeled as unpatriotic. Such rhetoric ignores the reality that women today aspire to education and careers, and that supportive policies, like childcare and parental leave, are far more effective in enabling family life than shaming or bribes.

Limited Support and “Coercive” Pronatalism: Perhaps the clearest sign of a regressive agenda is when governments push women to have more children without providing the social supports that make parenting feasible. For example, calls for more babies often come from the same politicians who oppose expanding childcare, preschool, or healthcare. In the U.S., there is still no federal paid maternity leave and childcare remains exorbitantly expensive. As the Century Foundation observed, one-off incentives ‘do not even cover’ a fraction of the costs of raising a child, and all the proposals presume a very narrow family norm while ignoring longstanding inequities that influence reproductive decisions. In short, these plans reward births but do little to support life with a child. The subtext is that women should embrace motherhood as their primary role and not expect society to assist much, a pronatalist stance that is deeply anti-feminist.

Abortion Bans and Reproductive Control: In its most overt form, pronatalism slides into outright coercion by denying women reproductive autonomy. We see this in places like Poland, where a nationalist government’s push for higher birth rates went hand-in-hand with a near-total ban on abortion in 2020. The ban, enacted under the banner of “pro-family” values, has forced women to carry unviable pregnancies. Similarly, in the United States, the reversal of Roe v. Wade in 2022 empowered numerous states to outlaw abortion, a move celebrated by pronatalist and conservative groups.

This coercive pronatalism is a dangerous step backward for human rights. It treats women less as citizens with agency and more as wombs on duty - for the family and their nation. The backlash has been significant, from mass protests in Poland to shifts in public opinion in the U.S., but the trend is clear: fear of population decline can fuel policies that sacrifice women’s freedoms, whether through subtle pressure or outright force.

It is crucial to emphasize that coercive or morally prescriptive strategies for influencing fertility rates are not only unethical but also demonstrably ineffective. Countries that have managed to stabilize their fertility rates, such as Sweden and France during the 2000s, achieved their outcomes through supportive, voluntary measures including subsidized childcare, generous parental leave, and flexible working arrangements, rather than through punitive measures or moralistic campaigns. Nevertheless, despite these comprehensive social policies, fertility rates in both nations remain significantly below the replacement level of 2.1, with Sweden at approximately 1.66 children per woman and France at around 1.83.

Profound social forces are fundamentally reshaping the relationship between parents and children

Profound social forces in developed nations are fundamentally reshaping the relationship between parents and children, directly impacting the desire to have any children. Over the past three generations, the child's role in defining family life has become increasingly dominant, significantly altering parenting styles. The traditional model, characterized by informal, family-guided child-rearing rooted in personal intuition and communal wisdom, has steadily given way to an intensely child-centric, expert-driven approach. Parents now devote unprecedented amounts of time, emotional energy, and financial resources toward securing their children's future, driven by the belief that they alone bear ultimate responsibility for their children's success. As one scholar describes it, this phenomenon of ‘intensive parenting’ underscores a prevailing notion of ‘parental determinism,’ which posits that parents are the principal architects shaping their children's destiny—overshadowing structural realities such as poverty, employment, discrimination, and housing.

The tangible effects of this shift are starkly evident in Norway. Despite boasting some of the world’s most generous parental leave policies, heavily subsidized childcare services, and exceptional standards of living—earning Norway a global reputation as one of the most supportive countries for raising children—the nation's birthrate has dramatically declined. Over the past two decades, Norway’s fertility rate has fallen sharply from 1.98 children per woman in 2009 to a historic low of 1.40 in 2023. This downward trend persists despite policies offering parents twelve months of shared paid leave following a child’s birth, alongside additional leave entitlements thereafter.

Raquel Herrero-Arias, an associate professor at the University of Bergen specializing in parenting dynamics, observes that recent years have seen "a clear intensification of parenting." She notes that "raising children has become more demanding, more complex, and more expansive, involving tasks and responsibilities not traditionally linked with the parental role." Young adults witness firsthand the enormous demands, both emotional and financial, imposed by this style of intensive parenting, observing parents sacrificing personal ambitions, social lives, and leisure to fulfill perceived obligations toward their children's happiness and success. Consequently, despite Norway’s comprehensive family-friendly programs, such heightened cultural expectations surrounding parenthood have inadvertently diminished its appeal.

Young individuals, understandably weighing the profound implications of such intensive child-rearing, are increasingly questioning whether parenthood aligns with their own life aspirations. Even the most robust social support frameworks prove insufficient in reshaping this emerging parenting paradigm, given the profound personal commitments and sacrifices it entails.

Prosperity Without Continual Population Growth

Modern capitalism, historically intertwined with continual growth in population, consumption, and resource extraction, stands at a critical crossroads: can it adapt and survive if populations stabilize around 8 million over the next century? The answer is yes, but only if capitalism itself evolves dramatically. Traditional capitalism has thrived on expansion, requiring ever-increasing numbers of consumers, workers, and markets. However, stable or even moderately declining populations do not inherently threaten capitalism; rather, they challenge the fundamental assumptions underlying conventional growth-driven economic models.

A stable population forces capitalism to shift its focus from quantitative expansion, producing more goods for more people, to qualitative growth, emphasizing innovation, sustainability, and improving living standards within ecological constraints. Instead of endlessly extracting more resources and generating more waste, capitalism would need to reorient towards efficiency, durability, and circularity. Businesses would succeed not by increasing scale alone, but through continuous improvement of products and services, creating value from innovation, technological advances, and sustainable practices.

Sweden offers a compelling illustration of how economic vitality can flourish alongside a stable population. Driven not by sheer demographic expansion but rather by investments in high-quality education, continuous productivity improvements, and technological innovation, Sweden demonstrates that growth is not inherently dependent on population increases. Indeed, over the past fifty years, Sweden's population grew by a modest 27 percent, yet during that same period, its economy expanded nearly threefold in real terms. This clearly highlights that forward-thinking policies and strategic development, rather than numerical growth alone, can sustainably support economic prosperity.

For capitalism to thrive in a stable or declining population context, it must overcome its traditional short-term profit motive and embrace broader societal goals, including environmental stewardship, equitable wealth distribution, and intergenerational responsibility. A capitalism redefined in this way, what some call ‘stakeholder capitalism,’ can remain dynamic and prosperous without relying on perpetual demographic growth. Ultimately, the question is less whether capitalism can survive with a stable or even declining population, and more whether our economic mindset is flexible enough to redefine prosperity itself, prioritizing human well-being and environmental health over mere numerical expansion.

Falling birth rates do pose challenges under the current economic paradigm, but they are far from insurmountable. In fact, several emerging trends and technologies directly counter the pessimism of the underpopulation narrative. Rather than reverting to 19th-century social policies, societies can embrace 21st-century solutions. Here are three transformative developments that reduce our reliance on ever-growing populations.

Innovation and Adaptation: Humanity’s Tools to Thrive with Fewer Births

Fertility Technology and Reproductive Choice.

Advances in reproductive medicine are extending the window of fertility and helping families have children who might not have been able to otherwise. In vitro fertilization (IVF) and related assisted reproductive technologies have become increasingly common and successful. IVF use in the U.S. doubled from 2012 to 2021, resulting in millions of births globally that wouldn’t have occurred naturally. Recognizing the value of IVF, President Trump signed an executive order in 2025 to expand access to IVF by lowering costs, acknowledging that high infertility treatment costs were a barrier for many would-be parents.

Meanwhile, egg-freezing is growing more accessible, allowing women to postpone childbearing if they wish, along with improved IVF techniques holds promise to further boost fertility options in the future. All this means that lower birth rates aren’t a permanent fate, if people desire children, technology can help facilitate it, even in the face of biological constraints like age or infertility. For example, countries like Israel have embraced IVF on a wide scale (with public funding), attaining relatively high birth rates despite later marriage ages. The bottom line: reproductive technology is turning the tide against ‘inevitable’ fertility decline, giving females more control over the reproduction process.

Longer, Healthier Lives – the Longevity Revolution

Alongside lower birth rates, we are also witnessing higher life expectancy and healthier aging, a triumph of development that will lead to offsetting many of the impacts of fewer babies. Thanks to medical and public health advances, people are living longer and staying vigorous later in life. Global life expectancy now exceeds 70 years in most countries. Since 1925, the life expectancy of women in the United States has increased significantly. In 1925, a newborn American girl could expect to live approximately 71.2 years. By 2023, this figure had risen to 81.1 years, reflecting an increase of nearly 10 years over the past century. This substantial gain in longevity is attributed to various factors, including advancements in medical care, improved public health initiatives, better nutrition, and enhanced living conditions.

In 2020, for the first time in history, the number of people over 60 years old outnumbered children under 5. This demographic shift need not spell crisis if we adapt our social and economic systems. With more healthy seniors, societies can encourage extended work lives, intergenerational mentorship, and volunteerism from older adults. Many nations are already raising retirement ages and finding ways for seniors to remain involved in the economy. The traditional dependency ratio of workers vs. retirees becomes less daunting if the definition of ‘dependent’ shifts. A 70-year-old today is often far healthier and more capable than a 70-year-old of generations past.

Moreover, the burgeoning field of longevity research is seeking to further postpone the illnesses of old age. Life extension programs, driven by groundbreaking advances in biotechnology, medicine, and geroscience, hold the transformative potential to greatly extend life by the end of this century. These emerging technologies target not just longevity, but also the quality of life, enabling individuals to remain healthier and productive significantly longer than current averages.

Innovative research areas such as regenerative medicine, genetic therapies, senolytics (drugs targeting aging cells), and personalized health monitoring powered by artificial intelligence are already showing promising early results. Leading figures in the field of longevity research are increasingly optimistic about extending human lifespans well beyond 100 years. Futurist Ray Kurzweil predicts that by 2029, medical advancements will enable us to add more than a year to our life expectancy for each year that passes, a concept known as ‘longevity escape velocity.’

Aubrey de Grey, a prominent biomedical gerontologist, shares a similar outlook. He estimates a 50 percent chance that we will achieve longevity escape velocity by the mid-2030s, allowing individuals to maintain health and vitality indefinitely through continuous medical interventions. However, not all experts concur regarding the rapid timeline proposed for these breakthroughs. Many researchers contend that achieving significant advancements sufficient for radical life extension remains improbable within the next half-century, given the immense complexity of fully understanding and intervening effectively in the aging process. Nonetheless, there is broad consensus that dramatically extending human lifespans is ultimately within the realm of scientific capability. Despite differing perspectives on the timeline, the quest to significantly prolong healthy human life continues to accelerate, driven by ongoing research and groundbreaking technological innovations determined to redefine the very boundaries of human aging. Ultimately this research will lead to completely upending global demographics.

The demographic implications of these advancements could profoundly reshape aging societies grappling with falling birth rates. Extended healthspans and ultimately lifespans over the next 50 years would partially offset the economic pressures associated with a shrinking younger workforce, as older populations remain economically productive and socially active far much longer periods. Countries currently facing demographic declines, such as China, Japan, South Korea, and much of Europe, will see a reduced need to encourage higher birth rates, instead investing in healthy aging infrastructure and technological innovation.

China, for example, currently maintains artificially low retirement ages, typically around 60 for men and as young as 50 to 55 for women, in part to accommodate the vast cohorts of younger workers entering the job market. This policy was originally designed to promote employment opportunities for younger generations in a rapidly expanding economy. However, as lifespans will continue to increase, individuals will be increasingly capable of contributing economically for much longer periods, often remaining productive for an additional 20 years or more beyond current retirement thresholds. Extending working years through incremental adjustments to retirement age would not only help countries with declining populations mitigate labor shortages caused by demographic shifts but also maximize the productivity and experience of older workers, creating more balanced and sustainable economic futures.

Thus, rather than viewing declining fertility rates as existential threats, aging societies might embrace life extension as a powerful tool, transforming what might appear as demographic challenges into opportunities for sustained economic and social vitality well into the future.

The Future Workforce

Perhaps the most significant force offsetting the challenges posed by population decline in rapidly aging societies is the accelerating integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics into the workforce. These transformative technologies are reshaping the very fabric of labor, providing innovative and effective solutions to workforce shortages caused by declining birth rates. Countries already grappling with demographic pressures have increasingly embraced automation as an essential lifeline, embedding advanced robotics into their manufacturing sectors. South Korea, for example, leads globally with an impressive deployment of 1,012 robots per 10,000 workers, followed by China with 470 (who annually install 50 percent of robots globally), and Japan with 419. By contrast, the United States has deployed only 295 robots per 10,000 workers, a reflection of America's continued population growth, and service sector focus, which lessens the urgency of automation as a tool to sustain economic productivity.

This is, however, merely the beginning of a sweeping technological transformation. As artificial intelligence advances rapidly, AI-powered robots will increasingly move beyond traditional factory assembly lines and permeate nearly every aspect of commerce and service industries. Moreover, AI-driven agents are poised to take over extensive segments of the office workforce, fundamentally reshaping roles in fields such as finance, law, administration, and software development. At Google, AI now handles approximately one-third of all coding tasks, dramatically accelerating development processes and setting a new standard for productivity.

Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei has made a bold prediction regarding the future of software development: within the next 12 months, AI will be responsible for writing nearly all code. Speaking at a recent Council on Foreign Relations event, Amodei stated that AI could handle 90 percent of coding tasks within three to six months and potentially reach 100 percent within a year. He emphasized that while human oversight remains crucial for now, the trajectory points toward AI taking over the entirety of coding responsibilities in the near future. This perspective is echoed by other tech leaders. Amazon Web Services CEO Matt Garman suggested that within two years, most developers might not be writing code themselves. In a leaked internal discussion, Garman highlighted the shift in developers' roles from coding to focusing on innovation and understanding customer needs, as AI takes over routine programming tasks.

Similarly, major law firms are employing AI tools to conduct document reviews, streamline contract analysis, and automate routine legal research, significantly enhancing efficiency and accuracy. In finance, algorithmic systems powered by AI have transformed stock trading, risk assessment, and portfolio management, allowing for faster, data-driven decisions that previously required large teams of analysts.

This transformative wave of AI-driven automation holds profound promise not merely as a means of addressing labor shortages in aging societies, but as a catalyst capable of revolutionizing productivity and economic efficiency. By empowering a dramatically smaller workforce to achieve significantly more, these advanced technologies enable societies to maintain vibrant economic growth, high standards of living, and enduring prosperity despite shifting demographic realities. Rather than facing shortages of labor, developed societies will increasingly need to grapple with a new and pressing challenge: ensuring meaningful, fulfilling employment opportunities for those individuals who freely chose to seek purposeful engagement in the workforce.

Importantly, technology is far from static. AI capabilities are growing at an exponential rate, indicating that our reliance on human labor for sustained economic growth will markedly diminish over the coming few decades. As these trends continue, economic productivity will no longer be directly tied to population size or the number of active workers. Instead, productivity and economic strength will increasingly rely on technological innovation and AI-driven efficiency. Societies that proactively invest in these advanced technologies will experience robust growth and prosperity, even as their populations stabilize or significantly decline. Ultimately, the progression of AI and robotics suggests a future economy characterized not by human labor scarcity, but by unprecedented efficiency, productivity, and potential abundance.

Where We’re Heading - Current United Nations Global Population Projections to 2100

The United Nations World Population Prospects (UNWPP) is a comprehensive series of population estimates that provides demographic data and analyses for 237 countries and areas. UNWPP has provided insights into global, regional, and national population trends from 1950 to the present, with projections extending to 2100. UNWPP projects that the global population will reach approximately 10.18 billion people by 2100. This projection is based on assumptions about future trends in fertility, mortality, and international migration. This represents the most likely trajectory according to the UN’s analysis, though considerable uncertainty exists in long-term demographic forecasting. Key drivers include declining fertility rates globally, albeit at different paces across regions, and continued improvements in life expectancy, which are already factored into this baseline.

As we’ve discussed, many developed countries, particularly those with sustained low fertility rates and aging populations, are projected to experience significant demographic shifts, including population decline. Demographic trends in key East Asian economies like Japan, China and Korea, which face significant population pressures.

Case Study: Japan

Japan stands out as a country projected to undergo a particularly dramatic population decline. According to the UN WPP 2024 data:

- Population (2024): 122.6 million

- Projected Population (2050): 103.8 million

- Projected Population (2100): 73.6 million

- Projected Change (2024-2100): -40.0%

Case Study: Republic of Korea

The Republic of Korea (South Korea) is another East Asian nation facing significant demographic headwinds, characterized by extremely low fertility rates.

- Population (2024): 51.8 million

- Projected Population (2050): 45.8 million

- Projected Population (2100): 29.6 million

- Projected Change (2024-2100): -42.76%

Case Study: China

China, despite its large population base, has also entered a period of demographic transition marked by slowing growth and an aging population, with population decline beginning in 2022.

- Population (2024): 1.425 billion

- Projected Population (2050): 1.313 billion

- Projected Population (2100): 766.7 million

- Projected Change (2024-2100): -46.2%

Demographics and the Implications for Future Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Global warming and ecological degradation arise primarily from the complex interplay of three key variables: global population size, consumption habits, and per capita energy usage. Increasingly aspirational consumer lifestyles worldwide, and the intensive energy demands needed to sustain them, have entrenched humanity on a path toward continuously escalating greenhouse gas emissions, despite decades of governmental promises to curb such trends. To explore plausible trajectories for future emissions, we have modeled a scenario in which global consumption and energy use patterns gradually align with the European Union’s current per capita emissions average, a figure approximately 40 percent lower than that of the United States today. Such a convergence provides a valuable benchmark for assessing the feasibility of achieving sustainable emissions levels while still maintaining relatively high standards of living.

To model energy consumption, we utilized the metric of energy intensity, defined as the total energy consumed, commonly expressed in kilowatt-hours, relative to gross domestic product (GDP), adjusted for inflation. Between 1990 and 2020, global energy intensity consistently declined by an average annual rate of approximately 1.7 percent, reflecting steady improvements in energy efficiency, economic restructuring, and technological innovation. Looking ahead, it is reasonable, and indeed likely, that improvements in global energy efficiency will accelerate beyond this historical rate. Nevertheless, greenhouse gas emissions are projected to continue their steep upward trajectory, driven predominantly by ongoing population growth and rising consumption patterns worldwide—forces currently overwhelming the beneficial effects of increased energy efficiency.

Baseline Greenhouse Gas Emissions Projections (2050 and 2100)

To establish a clear baseline for projecting future greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, we integrated medium-variant global population forecasts from the United Nations World Population Prospects (WPP) 2024 report with standardized per capita emission benchmarks. Specifically, we adopted the European Union's current average per capita emissions—approximately 10.7 tons of CO₂ equivalent annually—as an aspirational target for global convergence by 2050. Further, we set a more ambitious goal of reducing this benchmark by 50 percent by the year 2100, aligning future global emissions with the current energy intensity of many developing nations.

These emission goals, while challenging, represent attainable targets within the context of anticipated technological advancements and expected political and economic realities. Nonetheless, they remain significantly lower than current per capita emissions in several high-emitting countries, including the United States (17.6 tons), Russia (13.3 tons), South Korea (13.1 tons), China (11.1 tons), and Gulf states such as the United Arab Emirates (21.4 tons) and Bahrain (34.2 tons). The proposed emissions range of approximately 4 to 5 tons of CO₂ equivalent per capita by 2100 closely aligns with present-day emissions in nations such as Vietnam, Uzbekistan, and Mexico, underscoring a realistic and pragmatic view of future emissions.

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), global primary energy consumption is expected to increase by approximately 34 percent by 2050 compared to 2022 levels. This growth is attributed to factors such as rising living standards, industrialization, and population increases, particularly in non-OECD countries. The consulting firm McKinsey projects that by 2050 renewables will account for 75 percent of global electricity generation. Although an important step towards lowering GHG emission, electricity accounts for just 30% of global GHG emissions. While other GHG sources will continue to lower their emissions under expected technology improvements they will still emit near half of what they do today.

Looking further ahead, current projections suggest that global energy demand may more than double by the year 2100, with many analyses forecasting increases of up to 125 percent. Such substantial growth inevitably raises concerns about the capacity of our existing energy infrastructure to sustainably meet future requirements. Despite widespread governmental declarations committing to achieving 'net zero' greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, the persistent postponement of meaningful emission reductions, coupled with the continued year-over-year increases in emissions, casts doubt on the feasibility of these ambitious targets. Consequently, adopting benchmarks of approximately 10 tons of CO₂ equivalent per capita by 2050 and 5 tons by 2100 represents a realistic and pragmatic approach to evaluating the climate impact of anticipated population expansion and rising global standards of living. These targets provide a solid foundation upon which to measure progress, ensuring climate policy remains both ambitious and grounded in attainable realities.

Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions Forecast

Baseline Year 2025

- Global Population: Approximately 8.22 billion people.

- Total GHG Emissions: Approximately 53 Gigatons (Gt) of CO2 equivalent.

For the Year 2050

- Projected Global Population (Baseline): Approximately 9.66 billion people.

- Projected Total GHG Emissions: Approximately 97 Gigatons (Gt) of CO2 equivalent.

For the Year 2100

- Projected Global Population (Baseline): Approximately 10.18 billion people.

- Projected Total GHG Emissions: Approximately 51 Gt of CO2 equivalent.

The Remaining Emission Budget to keep Global Warming Under 3C

Despite governmental commitments over the past two decades to significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions, we remain on track to continue emitting at current levels for the foreseeable future. At present, approximately 1,000 gigatons (Gt) of carbon dioxide equivalent remain within the global emissions budget if we are to limit global warming to under 2°C by the year 2100. Yet, given ongoing trends in population growth and rising consumption patterns, we are likely to exhaust this entire carbon budget well before 2050. Such a trajectory would irrevocably place humanity on a perilous course toward a temperature increase of 3°C or more by the century’s end. These sobering projections underscore the immense scale and urgency of climate action. Even the most optimistic scenarios, characterized by significant advancements in energy efficiency and moderated consumption patterns, are unlikely to be sufficiently transformative to avert severe consequences entirely. As such, societies must not only pursue ambitious mitigation strategies but also rigorously prepare for the profound impacts that appear increasingly unavoidable.

The Consequences of a 3°C increase in average global temperature by 2100

The 3°C increase in average global temperature by 2100, well above the Paris Agreement targets, will have profound and far-reaching impacts. Recent research and assessments indicate this level of warming will drastically alter economic systems, natural environments, food and water resources, and geopolitical stability. Below is a structured overview of the expected impacts, drawing on the latest models and authoritative sources like the IPCC and UN agencies.

Economic Impact

A 3°C warming scenario is projected to inflict severe global economic losses. Updated models that account for extreme weather and global supply-chain shocks find much larger GDP declines than previously estimated. For example, a recent analysis from the UNSW Institute for Climate Risk & Response shows that a 4°C rise could cut world GDP by around 40 + percent by 2100. By comparison, limiting warming to 2°C is still projected to reduce per-capita GDP by roughly 16 percent. Other research models have found that a 3°C rise in 2100 would likely fall in between with more than a third of global GDP lost, implying tens of trillions of dollars in foregone economic output.

Such steep losses will result from multi-sector impacts and trade disruptions. As temperatures rise, labor productivity and industrial output are expected to suffer, especially in regions facing extreme heat. The agricultural sector would contract in many regions due to heatwaves and drought, and energy systems would face higher cooling demands and disruption of production (e.g. hydropower loss in droughts). Tourism and other climate-sensitive industries like outdoor recreation are also expected to significantly diminish in a 3°C world.

A major factor in this economic toll is the cascading disruption of global trade and supply chains. Traditional economic models often assumed that climate impacts are locally contained, but new research reveals that extreme events in one part of the world trigger knock-on effects globally. At 3°C, we can expect frequent ‘cascading supply chain disruptions’ as floods, storms or wildfires in key production hubs cripple exports and raw material supplies. No country is immune: even wealthier or higher-latitude countries that might experience milder direct climate effects are tightly linked to harder-hit regions through trade. These interconnected risks raise the likelihood of global financial crises triggered by climate shocks.

Specific quantitative projections underscore the stakes. The World Bank and insurance industry analyses have warned that in a high-warming scenario, global GDP will be significantly curtailed by mid-century. This represents permanent income loss on a scale comparable to, or exceeding, the Great Depression, spread across decades. Regional impacts will vary, with developing economies generally hit hardest due to higher vulnerability and less adaptive capacity. But even advanced economies could see ~10 percent or more knocked off their GDP by mid-century and by 2100, without stronger climate action, damages could diminish their GDP ~25 percent.

Finally, it’s important to note these estimates assume limited adaptation. While societies will try to adapt such as building sea walls, changing farming practices, and the like, there are limits to adaptation beyond 2–3°C. In short, a 3°C warmer world by 2100 will face a dramatically poorer global economy, with non-existent growth, persistent supply shocks, and substantial sectoral declines – an enduring climate-induced economic depression that hits all parts of the integrated global market.

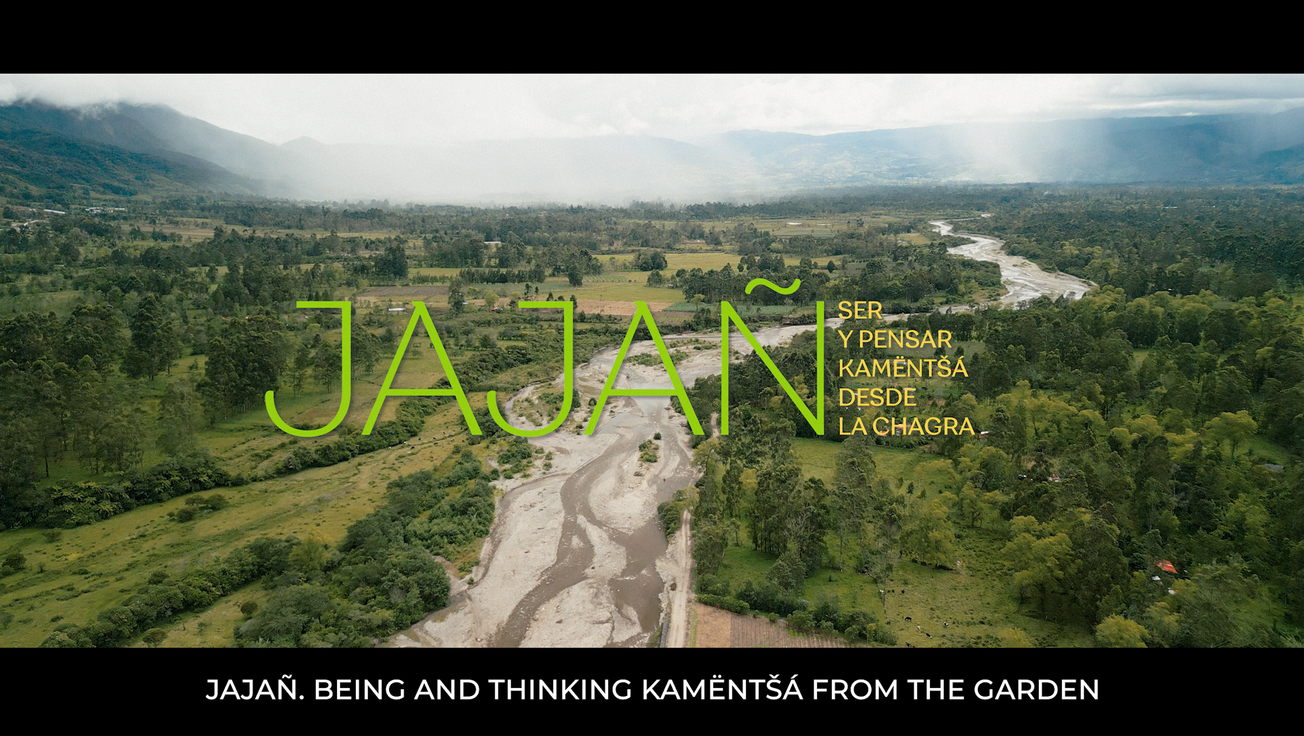

Environmental Consequences

A warming of 3°C would fundamentally transform Earth’s environment, bringing many systems to or beyond critical tipping points. Key expected consequences include significant sea-level rise, extensive biodiversity loss, major ocean chemistry changes, a surge in extreme weather events, and pronounced regional climate shifts.

Sea-Level Rise: Continued thermal expansion of the oceans and melting of ice sheets will raise global mean sea levels considerably by 2100. Under a mid-to-high emission pathway (~3°C by 2100), sea level is projected to rise roughly 0.5–0.8 meters by 2100 above late-20th-century levels. More alarming is the long-term commitment to even higher seas: reaching ~3°C warming will eventually trigger the irreversible loss of the Greenland Ice Sheet and parts of Antarctica. While the total melting of these ice sheets would unfold over centuries to millennia, it would raise sea levels by several meters in the long run, a catastrophic outcome for coastal communities and ecosystems. By mid-century, many coastal areas could see a tenfold increase in flooding frequency. Such changes would overwhelm existing coastal defenses, compromise small island states’ viability, and create millions of climate refugees.

Biodiversity Loss and Ecosystem Disruption: The natural world will suffer extraordinary stress under 3°C warming, with massive species losses and ecosystem transformations. The IPCC projects that at ~3°C, roughly one-fifth of terrestrial species and about one-third of marine species will be at very high risk of extinction. Particularly vulnerable are endemic species with narrow ranges: an estimated ~84 percent of endemic plant and animal species in mountainous regions will face extinction at 3°C, and essentially all endemic species on islands are likely to go extinct in such a scenario.

Even species not driven fully extinct will suffer range contractions and major population declines. Around 49 percent of insect species, 44 percent of plants, and 26 percent of vertebrate animals are projected to lose over half of their habitable range by 3°C warming, severely disrupting ecosystems and food webs. Iconic ecosystems are at particular risk: for example, tropical coral reefs are extremely unlikely to survive in a 3°C world. Kelp forests, mangroves, Arctic tundra, and boreal forests are all expected to undergo irreversible regime shifts under the stress of higher temperatures, droughts, and other climate extremes. The net effect is a planet with far less biodiversity and resilience. A poorer world not just in economic terms but in living natural heritage.

Ocean Acidification and Marine Change: A 3°C temperature rise corresponds to very high atmospheric CO₂ concentrations (from today’s 425 ppm to 600–800 ppm by 2100), which leads to significant ocean acidification. The oceans have already absorbed ~30% of human CO₂ emissions, causing surface pH to fall from ~8.2 to ~8.1. By 2100, under a high-emissions path, surface ocean pH is projected to drop by roughly 0.3–0.4 units. In practical terms, that means the ocean in 2100 would be about 150% more acidic than pre-industrial times – a chemical change not seen in millions of years. This acidification undermines the ability of calcifying organisms like corals, shellfish, many plankton to build their skeletons and shells. The shellfish industries and marine food chains that rely on pteropods and other calcifiers will collapse, with ripple effects up the food web.

Warmer waters also hold less dissolved oxygen, and stronger stratification limits oxygen replenishment at depth. By late century, subsurface ocean oxygen content could decline by ~8 percent globally creating expanding “dead zones” that severely diminish fish populations. Scientists warn of potential marine ecosystem collapse at 3°C, as multiple stressors interact in unpredictable ways. We are already observing amplified marine heatwaves and poleward migration of species; under 3°C warming, we could see major fisheries fail, coral reef systems functionally die off, and polar ocean ecosystems fundamentally altered as sea ice vanishes.

Extreme Weather Events: A 3°C hotter world would experience far more frequent and intense extreme weather. Heatwaves in particular would be unprecedented in scale. Many regions would see today’s record-breaking hot spells become routine summers. The tropics and subtropics, with higher baseline heat, would face even greater health and productivity impacts from extreme heat. Parts of South Asia or the Middle East could see periods that are physiologically unsurvivable being outside. Wildfire outbreaks are expected to intensify as well, with much more frequent mega-fire conditions in fire-prone areas such as the Mediterranean Europe, California and Australia.

Heavy precipitation and flooding events will also become more intense. A warmer atmosphere holds more moisture (about ~7% more water vapor per °C of warming), fueling extreme rainfall. Climate models project significantly increased risk of major river floods with each increment of warming. In a 3°C scenario, what were once rare downpours could occur regularly, leading to frequent flash floods and overflowing rivers in areas that today are not prepared for such extremes. Concurrently, the flip side is true in some regions: droughts are expected to become both more frequent and longer-lasting. At 3°C, roughly half of the Mediterranean region will be in drought at any given time, with the average drought lasting half the year. Overall, the pattern of extremes under 3°C is sometimes summarized as “wet gets wetter, dry gets drier.”

Regional Climate Shifts: Beyond these global trends, a 3°C warmer world means very different regional climates. Climate zones will shift poleward and upward in elevation. The Arctic is a clear example: it is warming at over twice the global rate. At 3°C global warming, the Arctic Ocean will be virtually ice-free in summer which is a state unprecedented in human history. Even at 2°C, the Arctic is likely to see ice-free summers occasionally. The loss of reflective sea ice will in turn accelerate warming (a feedback effect), and devastate ice-dependent wildlife like polar bears and seals.

Other regional shifts include a potential dieback of the Amazon rainforest. Higher temperatures and shifting rainfall would likely push the Amazon past a tipping point where it irreversibly dries into a savannah. Likewise, the west African monsoon and South Asian monsoon systems may become more erratic, challenging water management and agriculture for billions of people who depend on predictable monsoon seasons. In the mountains, the retreat of glaciers is another regional impact with global significance. By 3°C, nearly half of the ice in the Himalayas is projected to disappear. This meltdown imperils the headwaters of major Asian rivers (Indus, Ganges, Brahmaputra, Yangtze, and will lead to long-term water shortages for ~800 million people who rely on glacier-fed rivers. In North America, similarly, up to 85 percent of the glaciers in the Rockies and Western Canada will vanish by century’s end.

In summary, the environmental consequences of ~3°C warming by 2100 would be irreversible and Earth-changing. Regional climates would shift to the point of redefining where and how people can live. Each additional degree of warming vastly increases the risks and irreversible losses.

Food and Water Security

Climate change on the scale of 3°C poses a dire threat to global food and water security. The agricultural systems we rely on for food production are highly climate-sensitive, and freshwater resources in many regions are already stressed. Warming of 3°C would greatly exacerbate risks of crop failure, hunger, and water scarcity, potentially pushing many societies into famine or chronic water crises.

Agricultural Productivity: Crop yields are projected to decline sharply as global temperatures climb toward 3°C. Studies show that from 1°C to 3°C of warming, yields of the major staple crops of wheat, maize, rice and soy will fall in most regions. Crop models incorporating these factors project significant yield drops by late century under high warming. In some scenarios, global maize and wheat yields will decline 10–25% by 2100 at ~3°C warming, with losses of 50 percent or more in the hottest regions.

One manifestation of these impacts is a heightened risk of simultaneous crop failures in multiple “breadbasket” regions. Today, the likelihood of major synchronous failures when multiple top maize-producing regions all suffering a bad harvest in the same year is low. But with warming, this risk rises substantially. At 2°C warming, the probability of simultaneous severe maize crop failures across major exporters rises from ~6% historically to 54 percent and at 3°C it is even higher.

Hunger and Malnutrition: Declining yields and crop failures directly translate into higher food insecurity. Even by mid-century, climate change is expected to significantly increase hunger. if we reach 3°C: hundreds of millions of people, especially in Africa, South Asia, and parts of Latin America, may face chronic undernourishment. The IPCC has warned that beyond 2°C of warming, adaptive measures may no longer prevent widespread food supply disruptions. At 3°C, traditional adaptation like switching crop varieties or expanding irrigation will hit their limits. When high temperatures regularly exceed the tolerance of staple crops, there are only so many heat-resistant varieties available, and irrigation is of little use if water resources themselves are depleted.

Adaptation costs for agriculture will undergo an unparallel rise. Investments in drought-resistant crops, new farming practices, and infrastructure like irrigation and storage can alleviate some losses, but these come at a high price. By one estimate, at ~2°C warming the combined cost of adaptation and residual damages in global agriculture could reach $80–100 billion per year. At 3°C, the annual costs are projected around $128 billion annually. All of this foreshadows a real possibility of persistent famine in parts of the world.

Freshwater Availability: Climate change at 3°C will pose severe challenges for water security, as changing precipitation patterns and melting cryosphere alter water supplies. Many regions will face either too little water (drought) or too much (floods), and sometimes both in the same area at different times.

Migration and Political Stability

The social and political repercussions of 3°C warming will be massive. Climate change acts as a threat multiplier, exacerbating tensions over resources and triggering human displacement. In a 3°C scenario, we can expect large-scale migration, heightened stress on cities and governance, and an increased risk of conflict in vulnerable regions due to resource scarcity and social instability.

Climate-Driven Displacement: As environmental conditions deteriorate, many people will be forced to move. The World Bank’s Groundswell report (2021) estimates that, without keeping temperature increase below 2°C, up to 216 million people could be internally displaced by 2050 due to climate change impacts. While those climate migrants would mostly be moving within their own countries, their relocation will profoundly affect both origin and destination areas.

The drivers of such migration include sea-level rise, water scarcity, crop failure, and extreme events. Those migrants will head to cities or higher ground. In Vietnam’s case, from the delta to Ho Chi Minh City or the central highlands which concentrates pressure on urban areas. Urban stress will increase as millions of people relocate from climate-affected rural areas into cities that may already struggle with infrastructure and services.

Importantly, most climate-related displacement so far has been internal rather than cross-border. People tend to move to safer parts of their own country when possible. However, as conditions worsen, international migration will rise, especially as crises overwhelm nations’ capacity to support their populations. By the latter half of this century, a 3°C trajectory will likely put hundreds of millions of people at risk of climate displacement from various hazards – rising seas, more powerful cyclones, river flooding, drought, and extreme heat.

Pressure on Governance and Services: Climate stress will also aggravate political instability by undermining economies and straining government capacity. Countries that are highly exposed to climate impacts and that have limited resources or pre-existing conflicts face a particularly high risk of instability under 3°C warming. Droughts and water shortages can inflame regional disputes over water rights. Consider the Nile or Indus basins, as examples, where multiple nations share water. Similarly, in South Asia, issues like the India-Pakistan rivalry over water from melting Himalayan glaciers will be greatly exacerbated.

In summary, 3°C of warming by 2100 would have immense human and geopolitical consequences. We would likely see unprecedented human migration, placing heavy stress on cities and national governments to provide basic services. Societal inequalities would be laid bare, as poorer communities and countries struggle to adapt or move, fueling resentment and much worse. Climate change will increasingly act as a destabilizing force, multiplying the risk factors for unrest and conflict in many regions. The future is not predetermined. However, a 3°C world will be a more volatile and insecure place, with greater humanitarian crises and security challenges than we can imagine today.

Rethinking Population in the 21st Century

The doomsday narrative of “population collapse” falls apart under scrutiny. Yes, many societies are greying and seeing fewer babies, but humanity is not in free fall, and thoughtful policy can navigate these changes. In addressing underpopulation anxieties, we must separate genuine challenges, like caring for the elderly, or maintaining economic dynamism, from misguided panic fueled by nostalgia or bias. The latter has led to troubling responses, from xenophobic fears about who is having babies, to draconian measures pressuring women to reproduce. Such reactions are not only morally questionable, they also ignore the real levers we have to sustain prosperity and well-being in a world of lower fertility.

Rather than trying to force a higher birth rate through nationalist or fundamentalist crusades, policymakers and environmentalists would do well to embrace a more holistic vision: one that values quality of life, equity, and sustainability. This means defending reproductive rights and empowering women – allowing families to choose their size freely without stigma or hardship. It means adjusting our economies by investing in automation, encouraging healthy aging, and shifting away from growth-at-all-costs models. It also means recognizing that allowing the population to decline naturally can bring a host of benefits including easing pressure on ecosystems and climate, especially if it’s the high-consuming populations that reduce in size. The 21st century can be a period of demographic maturation for humanity: a phase where we stabilize our numbers, reduce our ecological footprint, and use our wealth of knowledge and technology to support everyone, young and old.

Ultimately, the core purpose of public policy is to foster human flourishing, a goal that cannot be realized by lamenting declining birthrates or romanticizing an idealized past. Rather than fearing demographic shifts, we must proactively embrace them, shaping our future through intelligent, compassionate policies attuned to emerging realities. Even if population growth slows or stops, human progress need not. Innovation, quality of life, and societal advancement have never been determined by population size. Indeed, during a period when Earth's population was only a quarter of today’s level, humanity witnessed our most prized breakthroughs: the harnessing of electricity, the invention of cars and airplanes, pioneering developments in rocketry, revolutionary advances in communication technology like telephones and television, medical milestones like penicillin, profound leaps in physics such as quantum theory and the discovery of the atomic nucleus, and groundbreaking steps in biology, including mapping genes onto chromosomes—just to highlight a few.

Our future success hinges not on sheer numbers, but on the investment we make in education, opportunity, and care for those alive today. By harnessing innovation and safeguarding fundamental human rights, we can reframe the narrative of population stability into an unprecedented generational opportunity, a chance to construct more sustainable, equitable societies, protect our planetary home, and secure a high quality of life for current and future generations alike. The sky is not falling; it is evolving, and our responsibility is to evolve with it, for the better.