1. Introduction and Context

The global energy transition is more than an environmental imperative, it is the defining economic and technological transformation of the 21st century. At its center are China and the United States, the world’s two largest economies and the leading emitters of greenhouse gases. The choices they make will shape not only their own energy security and competitiveness but also the direction of the global energy system for decades to come.

For the United States, the stakes could not be higher. The nation now confronts unprecedented challenges, intensifying global competition, mounting economic pressures at home, and a political system increasingly divided against itself. To preserve its leadership, America must rethink its core assumptions: that a purely market-driven, consumer-based economy, underwritten by a global military presence (euphemistically renamed the “Department of War”), can remain the engine of growth and security. The question is unavoidable: do our current policies even speak to the kind of competition that will define future prosperity and national strength, or are we clinging to models of the past while rivals design the frameworks of tomorrow?

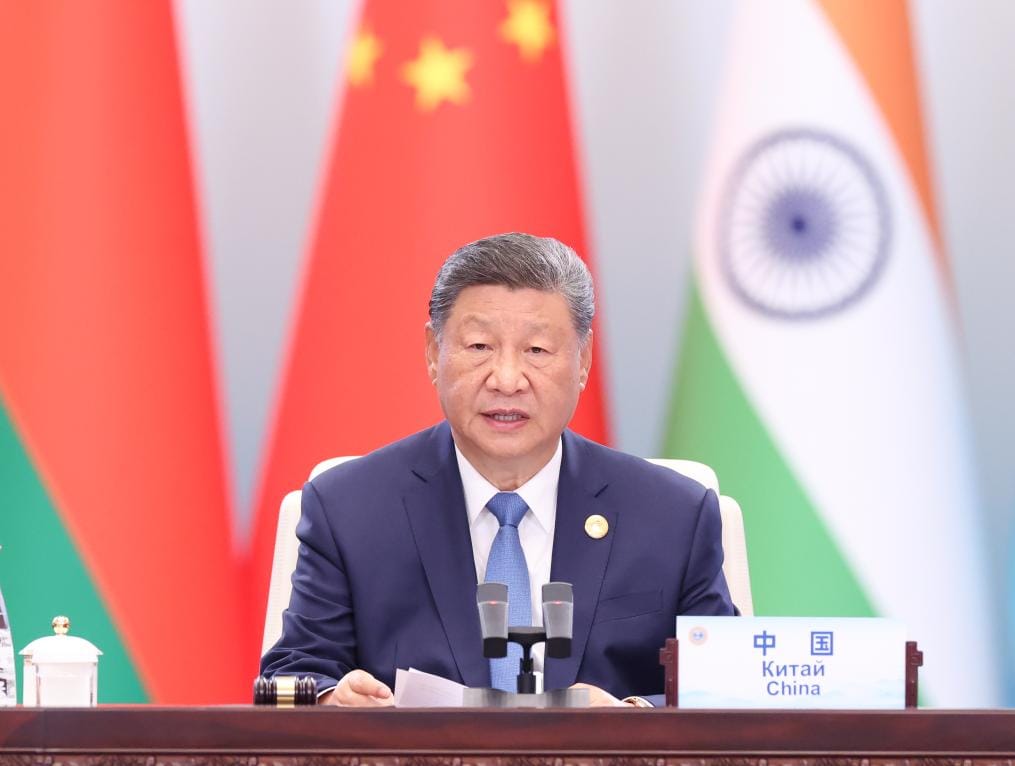

This competition intensified dramatically on September 1, 2025, when Chinese President Xi Jinping delivered a landmark address at the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) “Plus” Meeting in Tianjin. Flanked by the visible support of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Russian President Vladimir Putin, Xi unveiled a sweeping vision for regional energy cooperation. His proposals represent China’s most ambitious use of “Green Diplomacy” to date, leveraging renewable energy not only as a developmental tool but as a key geopolitical instrument in its rivalry with the United States.

The symbolism of Modi and Putin’s endorsement was striking. For India, participation signaled a pragmatic calculation: despite ongoing border disputes with China, New Delhi sees strategic value in accessing SCO-driven investment and infrastructure to advance its ambitious domestic renewable targets. For Russia, the alignment underscored its partnership with Beijing, as Western sanctions erode its traditional oil and gas markets. Together, their support amplified the message that Xi’s initiative is not a unilateral Chinese project but a multilateral energy order with broad Eurasian backing.

At the heart of the Tianjin declaration was a plan to construct an integrated, multinational renewable energy ecosystem spanning the vast Eurasian landmass. More than an energy initiative, it marks a bold escalation in Beijing’s drive to establish a China-centered alternative to Western-led energy systems, one that could ultimately bind 27 SCO member and partner states, representing more than 40 percent of the world’s population, into a cooperative bloc anchored by Chinese technology, financing, and infrastructure.

China has placed a bold and global bet on renewables, constructing the infrastructure not only to power its own vast domestic economy but also to become a global supplier of both clean energy technologies and unprecedented flows of renewable electricity. The United States, by contrast, is charting a starkly different path under President Trump: cementing its role as the world’s largest oil producer and leading natural gas exporter, shipping 1.9 billion cubic feet of LNG abroad every single day. The divergence could not be more striking. China is racing to dominate the industries of the future, while the United States is entrenching itself in the fossil-fuel paradigms of the past.

The structural realities of each nation’s energy system help explain the sharply divergent paths they are now pursuing. The United States, as a net exporter of fossil fuels, approaches the energy transition from a position of relative resource security. China, by contrast, is the world’s largest importer of oil, gas, and coal, leaving it deeply exposed to external supply shocks. This dependency helps drive Beijing’s determination to accelerate renewable deployment at home and abroad.

In 2024, China consumed 80% more total energy than the United States, reflecting its role as the world’s manufacturing hub, producing nearly 30% of all global manufactured goods compared with just 16% produced by the U.S. But despite China’s vast industrial output, Americans still consumed more than twice as much energy per person. This paradox underscores the profound differences in how the two economies use, and depend on, energy, shaping their contrasting strategies for the future.

On efficiency, the divide between China and the United States is quickly narrowing. In 2000 China required more than three times as much energy as the United States to produce the same dollar of output, an efficiency gap of roughly 200%. Since then, China has made enormous gains through industrial restructuring, efficiency upgrades, and the growth of its service sector. By the early 2020s, the gap had narrowed to about 30%, reflecting China’s rapid progress in decoupling growth from energy use.

Over the past two decades China has shown an extraordinary ability to engineer rapid structural change. It has shuttered outdated steel mills, massively expanded renewable capacity, and invested heavily in efficiency upgrades across its industrial base. If China can sustain its average annual improvements in energy intensity of 3–4%, it is likely that it will close the 30% efficiency gap with the United States within the next decade.

Such a convergence would be far more than a statistical milestone. It would signal China’s success in decoupling economic growth from energy consumption at scale, a breakthrough with profound global consequences. Eliminating the gap would not only cut their greenhouse gas emissions dramatically but also sharpen China’s competitive edge in clean industries. Perhaps most importantly, it would establish Beijing as the credible leader in defining the rules and standards of the emerging clean energy economy, shifting the balance of power in the global transition.

For the United States, the prospect of parity carries serious implications. A China that matches American efficiency while maintaining its industrial dominance would heavily tilt the balance of global competitiveness toward Beijing. Out of these differences have emerged two sharply contrasting strategies for the energy transition. What hangs in the balance is far greater than national energy portfolios. This divergence will determine who captures leadership in the energy revolution and who risks being consigned to the margins of a rapidly changing global economy.

2. Strategic Imperatives: Energy Security and Environmental Concerns

China’s aggressive push into renewable energy is rooted in two strategic imperatives: reducing its dependence on foreign fossil fuels and mitigating the environmental crisis at home. As the world’s largest importer of oil and natural gas, Beijing sees this reliance as a profound vulnerability. Much of that energy must transit the Strait of Malacca and other maritime chokepoints patrolled by U.S. and allied navies. This so-called “Malacca dilemma” has long haunted Chinese strategists, who recognize that in the event of unresolved differences or conflict, a blockade by the U.S. would strangle China’s economy within weeks. The historical memory of Japan’s oil dependency before World War II, when U.S. embargoes and naval dominance were partly behind Tokyo’s desperate decisions, remains an unmistakable parallel in Chinese strategic thinking.

To hedge against this threat, Beijing is pursuing a two-pronged response. The first prong is the massive scaling of renewables—solar, wind, hydropower, and the grid infrastructure to transmit them nationwide. By replacing imported oil and gas with domestic renewable capacity, China reduces its exposure to maritime vulnerabilities while also tackling deadly air pollution and climate risks. Energy independence through renewables is, in this sense, not only an environmental measure but also a shield against foreign coercion.

The second prong is the rapid expansion of China’s naval power. The People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) is now the world’s largest fleet by number of ships, with an expanding blue-water capability that includes aircraft carriers, advanced submarines, and long-range anti-ship missiles. This buildup is designed to deter or complicate any U.S. attempt at a Malacca blockade, securing China’s sea lanes for energy imports and trade. In Beijing’s eyes, energy security cannot rest solely on domestic renewables; it also requires the ability to defend critical supply routes through the South China Sea, the Indian Ocean, and beyond.

America has long based its security on naval supremacy because control of the seas ensures both economic and strategic dominance. Since World War II, the U.S. Navy has guaranteed the free flow of goods and energy across the world’s maritime chokepoints, from the Strait of Hormuz to the Strait of Malacca, allowing Washington to underwrite the global oil and trade system. This maritime dominance gave the U.S. unparalleled leverage: it could protect allies’ supply lines, secure its own access to key resources, and, when necessary, use the threat of blockade as a coercive tool against adversaries. Naval supremacy also allowed the U.S. to project power rapidly anywhere on the globe, anchoring its alliance system and reinforcing its role as guarantor of the postwar international order.

Today, China’s naval buildup directly challenges this foundation. From Washington’s perspective, Beijing is not only trying to insulate itself from potential U.S.-led blockades but also building the capacity to project power across its trade and energy corridors in the South China Sea, Indian Ocean, and beyond. This shift threatens to erode one of America’s most enduring strategic advantages, the ability to shape global security and economic flows through command of the sea.

But for the United States, this pursuit of global supremacy carries a mounting cost that is becoming increasingly difficult to sustain. In response, Washington’s strategic posture is shifting away from the goal of outright global dominance toward a more pragmatic focus on regional supremacy in key theaters. Rather than seeking to project overwhelming power everywhere at once, U.S. strategy now emphasizes consolidating allies influence in the Indo-Pacific, where the challenge from China is most acute. This approach rests on empowering key allies such as South Korea, Japan, and the Philippines to expand their own military and economic capabilities, thereby strengthening a regional balance of power that can serve as an effective hedge against Beijing’s growing assertiveness.

The Role of Central Planning and State-Owned Enterprises In Renewable Energy Development

Unlike the United States, China is a net importer of all forms of fossil fuels. China is the world's largest producer of coal, producing nearly five times as much as the next country, India. This explains coal's huge role in China's energy system. But despite its mammoth production, in 2022 China imported nearly 7% of its coal supply. China is the world's fifth-largest producer of crude oil, but its demand far outstrips domestic supply, making China the world's largest oil importer. Natural gas plays a much smaller role in China's economy than in the U.S. economy. China's domestic natural gas production has been rising, but it still imported 40% of its supply in 2024.

This import dependence has created significant geopolitical risks for China, as its energy supply lines are highly vulnerable to disruption. The Chinese government has therefore made energy independence a top national priority, and renewable energy is seen as a key pathway to achieving this goal.

At the heart of China’s renewable energy goals lies the commanding hand of the state. Unlike market-driven systems, China has pursued a top-down, state-led model that fuses national strategy with industrial execution. Through central planning, vast state investment, and the mobilization of powerful state-owned enterprises (SOEs), Beijing has treated renewables not as a niche industry but as a pillar of national security and economic competitiveness. This approach enables the government to set long-term targets, channel capital at unprecedented scale, and coordinate across sectors, from energy generation to grid infrastructure, manufacturing supply chains, and export policy. The result is a system capable of rapid mobilization and course correction, one that allows China to scale solar, wind, and battery technologies at a pace unmatched anywhere in the world.

Five-Year Plans and Industrial Policy

China’s renewable energy development has been guided by the country’s national Five-Year Plans, which serve as both economic roadmaps and instruments of industrial mobilization. These plans set ambitious targets not only for renewable capacity and production, but also for the technologies and supply chains that underpin them.

Unlike the crude five-year plans of the Soviet Union, which were largely based on rigid quota production goals, China’s planning process functions as a thoroughly designed strategic roadmap. It identifies priority sectors, allocates resources, and establishes mechanisms for innovation and market development, ensuring that targets are not only aspirational but also operationally achievable. In this sense, China’s Five-Year Plans resemble the long-term strategic planning models used by leading Western corporations, detailed, data-driven, and goal-oriented rather than the short-term, politically fragmented approach that often characterizes governance in western countries like the United States.

The turning point for renewables came in 2010 with China’s launch of the Strategic Emerging Industries initiative, which identified seven priority sectors, including new energy and new energy vehicles as the engines of China’s future growth.

Since then, each successive plan has expanded the scope of renewable ambition. Beijing has directed strategic investments into every dimension of the energy transition: scaling solar and wind capacity to record levels, advancing green hydrogen and geothermal projects, and pouring resources into battery storage and its global supply chains. The 14th Five-Year Plan (2021–2025) epitomized this approach, setting a target for renewables to provide 25% of electricity by 2025. Yet China has already blown past this benchmark, with renewables reaching 35% of power generation, four years ahead of schedule.

This pattern highlights a core feature of China’s model: when state power aligns with industrial capacity, targets are not simply met but often surpassed, reshaping the trajectory of the global energy system in the process.

State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs)

State-owned enterprises (SOEs) sit at the very center of China’s renewable energy transformation. Unlike in market-driven systems where private firms compete for dominance, China’s government-controlled giants act as both the architects and the builders of the energy transition. Backed by central and local authorities, these firms dominate every link of the renewable value chain, from manufacturing turbines and solar panels, to financing and developing projects, to integrating them into the grid and maintaining nationwide distribution.

It would be misleading, however, to view these firms as monolithic state entities. Although the state typically retains majority ownership stakes, many SOEs are publicly listed companies with significant private and even foreign shareholders. For example, the State Grid Corporation of China has subsidiaries that trade on domestic exchanges, while major power producers like China Three Gorges Renewables and China Huaneng Group list shares in Shanghai and Hong Kong, attracting global investors. Similarly, PetroChina, while majority-owned by China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), counts international institutions such as America’s BlackRock and Vanguard among its major shareholders.

This model is not unique to China. In many respects, it mirrors practices in European countries, where governments maintain strategic stakes in key sectors while allowing significant outside investment. For instance, the French government holds a controlling stake in EDF (Électricité de France) but foreign asset managers and private investors also own large portions of the company’s traded shares. Likewise, Enel in Italy is majority-backed by the state but has substantial international shareholder participation.

It’s an interesting paradox that American investment institutions that are managing capital from U.S. pension funds are channeling a large share of new investments into China and Asia, regions often portrayed politically as America’s principal competitors for future prosperity. As of 2023, U.S.-based asset managers such as BlackRock, Vanguard, and Fidelity collectively oversaw more than $20 trillion in global assets, with over $1.3 trillion allocated to Chinese and broader Asia-Pacific equities and bonds. BlackRock alone managed more than $430 billion in Asia-Pacific investments, including more than $150 billion in Chinese markets, making it one of the largest foreign stakeholders in China’s financial system. Vanguard, before scaling back some of its China operations in 2021–22, had directed more than $200 billion in client assets into Asia, while Fidelity’s allocations to Asian growth funds totaled more than $100 billion.

A significant share of this capital originates from American pension systems, particularly large public funds such as CalPERS (California Public Employees’ Retirement System), which reported over $30 billion invested in Chinese companies and Asia-focused funds, and the New York State Common Retirement Fund, with roughly $12 billion in China-linked holdings. In total, U.S. pension fund exposure to Chinese equities and bonds has been estimated at $300–400 billion, underlining the scale of financial interdependence between the two economies.

This paradox is not unique to the United States. European pension funds and sovereign investors have similarly increased allocations to China and Asia in recent years, seeking higher growth than mature Western markets can offer. For example, the Norwegian Government Pension Fund Global, the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund with over $1.6 trillion in assets, holds more than $40 billion in Chinese equities. The Dutch pension giant ABP has directed more than €20 billion toward Asia-focused equity and infrastructure investments, including stakes in renewable energy and transport projects in China. Likewise, Sweden’s AP funds and Germany’s Allianz Global Investors have expanded their China portfolios into both public equities and private infrastructure, often citing the country’s leadership in renewable energy, electric vehicles, and digital finance as strategic growth areas.

Taken together, these trends reveal a striking reality: while Western governments increasingly frame China as a strategic competitor, Western retirement savings are helping to fuel China’s rise in precisely those industries—technology, infrastructure, and green energy—that will shape global economic leadership in the decades ahead.

Flagship SOEs such as the State Grid Corporation of China, China Three Gorges Corporation, and the country’s “Big Five” state-owned power generation companies have spearheaded the rollout of renewable infrastructure at a pace and scale unmatched anywhere else in the world. Their coordinated efforts have enabled China to construct the world’s largest solar farms, deploy record levels of wind capacity, and expand ultra-high-voltage transmission lines capable of delivering renewable electricity across vast distances.

The role of SOEs highlights a fundamental feature of China’s model: when industrial power, financial capital, and political authority are fused under state direction, the barriers that slow deployment elsewhere such as financing risks, fragmented regulation, or community opposition can be rapidly overcome. In this way, SOEs have been not merely participants in the renewable energy boom, but the decisive instruments through which China has vaulted to global leadership.

By blending state control with market participation, China’s SOEs combine the strategic direction of public ownership with the capital and efficiency pressures of private investment, enabling them to scale rapidly while still aligning with national policy priorities. At the same time, top-down policies provide clear signals and targets that allow smaller private entrepreneurs to shape their product development in ways that directly support the needs of SOEs. Whether through specialized components for wind turbines, advanced software for smart grids, or niche innovations in battery technology, these firms can align their offerings with state-backed projects, secure reliable demand, and accelerate commercialization. This synergy between state-driven objectives and entrepreneurial responsiveness creates an innovation ecosystem in which SOEs achieve national goals more efficiently while private firms benefit from predictable markets and growth opportunities.

By contrast, many European state-owned companies operate within a far more fragmented political environment, where competing national and EU-level priorities often dilute decision-making and delay execution. A state-backed utility such as EDF in France or Enel in Italy must navigate layers of regulatory oversight, shifting coalition politics, and complex stakeholder processes before moving forward on major projects. This fragmentation makes it difficult to achieve the kind of scale and speed that Chinese SOEs can deliver when directed through a cohesive national strategy. The comparison underscores a central asymmetry: while Europe’s state-owned companies are constrained by political pluralism and regulatory fragmentation, China’s SOEs benefit from a unified political decision process that is similar to well-run corporations which aligns corporate action with long-term objectives, enabling achievements that Europe struggles to replicate.

China’s renewable energy program is underpinned by a state-directed financing model that mobilizes vast pools of capital from its state banking system. At the heart of this system are the China Development Bank and other state-owned banks, which serve as the primary financiers of renewable energy projects. By providing long-term, low-cost loans to SOEs and project developers, these institutions have enabled the rapid scaling of solar farms, wind projects, hydropower, and energy storage across the country. The government has further reinforced this financial backbone by establishing specialized funds and investment vehicles dedicated to accelerating clean energy deployment.

The results are staggering. In 2024 alone, China invested more than $625 billion in clean energy, the largest annual investment by any country. That outlay translated into the addition of 373 gigawatts of renewable capacity, equivalent to more than triple the total installed capacity of Germany’s entire power system.

Crucially, China has also achieved world-leading investment efficiency, deploying an average of one gigawatt of renewable capacity for every $1.68 billion invested. This extraordinary efficiency stems from its unmatched manufacturing scale, vertical integration, and the ability of the state to coordinate resources across the entire value chain. By contrast, the United States spends nearly twice as much capital per gigawatt of renewable capacity, roughly $3 billion per GW, due to higher labor costs, fragmented permitting processes, and lack of tightly integrated supply chains. America’s market-driven approach relies heavily on tax credits, private financing, and state-level regulation, which often produces slower deployment and more costly outcomes.

The disparity underscores more than just differences in cost. It reflects two fundamentally different models of energy transition. China’s state-led, scale-driven system allows it to translate investment into low cost, rapid capacity growth, while the U.S. system, though more decentralized and innovative in certain niches, struggles to achieve the same level of cost, efficiency or speed.

China’s financing model demonstrates how aligning industrial policy with financial power can achieve outcomes that far exceed what market-driven systems have managed. By marrying abundant capital with state-directed strategy, China is not only transforming its domestic energy system at unprecedented speed but is also cementing its global leadership in the technologies, supply chains, and cost structures that will define the future of clean energy.

America's Market-Driven Renewable Energy Patchwork

The United States is pursuing a fundamentally different path to renewable energy development than China. The U.S. depends on a market-driven system shaped by a complex interplay of federal tax incentives, state-level mandates, and private sector investment. The result is a patchwork of policies and regulatory frameworks that vary dramatically across states, with no single coordinating authority to set uniform national goals.

At the heart of U.S. renewable policy are two cornerstone mechanisms: the Investment Tax Credit (ITC) and the Production Tax Credit (PTC). These instruments have proven critical in lowering project costs and catalyzing private investment, but they operate through the tax code rather than direct state-led financing, leaving deployment subject to political cycles, market volatility, and the willingness of private investors to take on risk.

Investment Tax Credit (ITC):

- Structure: Provides a dollar-for-dollar reduction in income taxes based on the percentage of capital investment.

- Base Rate: 30% for projects ≤1 MW; 6% for projects >1 MW.

- Enhanced Rate: Up to 30% for larger projects that meet prevailing wage and apprenticeship requirements.

- Maximum Potential: 50% of eligible costs if all bonus criteria are met.

- Timeline: The 30% rate is extended through 2032, followed by gradual step-downs.

Production Tax Credit (PTC):

- Structure: Provides a per-kWh tax credit for electricity generated over a 10-year period.

- Base Rate: 0.6 cents/kWh; 3 cents/kWh if wage and apprenticeship standards are met.

- Bonuses: Additional 10% credit for projects using domestic content and another 10% for those located in designated “energy communities.”

- Duration: 10-year eligibility after equipment is placed in service.

Together, these tax credits have been instrumental in driving the expansion of wind and solar across the United States. But, compared with China’s direct state-led financing and centralized planning, America’s approach is highly fragmented, and often vulnerable to shifts in political leadership and polarization. This polarization creates a patchwork of policies, incentives, and regulations that often pull in opposite directions, undermining the possibility of a unified national strategy. Meanwhile China can set a five-year target and exceed it ahead of schedule, U.S. progress depends on the stability of tax policy, investor appetite, and the ability of state-level programs to fill the gaps, which has been uneven and problematic.

European state-owned companies operate within a fragmented political environment similar to the U.S., where competing national and EU-level priorities often dilute decision-making and delay execution. A state-backed utility such as EDF in France or Enel in Italy must navigate layers of regulatory oversight, shifting coalition politics, and complex stakeholder processes before moving forward on major projects. This fragmentation makes it nearly impossible to achieve the kind of scale and speed that Chinese SOEs can deliver when directed through a cohesive national strategy. The comparison underscores a central asymmetry: while Europe’s state-owned companies and America’s private corporations are constrained by political pluralism and regulatory fragmentation, China’s SOEs benefit from a unified political decision process that aligns corporate action with long-term state objectives, enabling achievements that the U.S. and Europe struggle to replicate.

Corporate Tax Policy Paradox Between U.S. and China

China and the United States take very different approaches to taxing large corporations, and the gap in effective corporate tax rates has become a major point of comparison in global competitiveness.

On paper, China’s statutory corporate income tax rate is 25%, roughly in line with the U.S. federal corporate tax rate of 21%. However, China provides a broad range of preferential policies, especially for high-tech enterprises, exporters, and companies aligned with state priorities like renewable energy and advanced manufacturing. Qualified “High and New Technology Enterprises” (HNTEs), for example, pay a reduced rate of 15%, and firms in key sectors often benefit from additional deductions, R&D super-credits, and local government tax incentives. As a result, the effective tax rate for many large Chinese companies is often closer to 12–18%, significantly below the statutory rate.

In the United States, the federal statutory rate is 21%, but the effective tax burden on large corporations has been even lower due to deductions, credits, and international profit-shifting strategies. A 2023 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report found that large profitable U.S. corporations paid an average effective tax rate of about 9% in 2019–2021, with some paying far less in certain years. Tech giants and multinationals with extensive use of offshore subsidiaries often report single-digit effective rates, despite high profitability.

This contrast highlights a paradox: both China and the United States use the tax code strategically, but in very different ways. China explicitly ties its preferential tax regime to state priorities, channeling capital into targeted industries such as renewable energy, semiconductors, and advanced manufacturing. By doing so, Beijing ensures that lower effective rates are conditional on firms advancing national objectives. U.S. corporations, by contrast, achieve low effective rates from aggressive tax planning, deductions, and loopholes rather than a deliberate industrial strategy. The outcome is striking: in the United States, about one in ten Fortune 500 companies pays no federal income tax in a given year, whereas in China, while many large firms benefit from significantly reduced effective rates, virtually none report zero corporate tax liability, since preferential treatment is earned through compliance with industrial policy rather than the exploitation of loopholes.

Renewable Energy Breakthroughs Are Not Confined To Market-Driven Innovation

In the United States, the dynamism of the private sector is often held up as the chief driver of renewable energy progress. Politicians and industry leaders point to breakthroughs in solar module efficiency, wind turbine design, and innovative financing structures as evidence that innovation flourishes best in a private-sector, market-driven environment. This narrative is frequently used to argue against more supportive government programs, like those found in Europe and China, reinforcing the idea that federal intervention is unnecessary, or even counterproductive, because private enterprise alone can deliver the needed results.

Europe is often seen as a leader in climate policy and renewable deployment, but when it comes to core technology and innovation, it is lagging behind the United States and, increasingly, China. Several structural factors explain this gap. One is Europe’s fragmented political and regulatory landscape. The European Union sets ambitious climate goals, but implementation is left to member states. This produces a patchwork of incentives, permitting regimes, and grid rules that slows project timelines and makes scaling technologies more difficult. Projects in Europe can be bogged down for a decade by environmental reviews, community opposition, and national politics.

Another factor is underinvestment in R&D. Europe spends heavily on deployment subsidies such as feed-in tariffs but relatively less on deep research and engineering. For example, Europe was once the global leader in solar manufacturing, but firms like Q-Cells and SolarWorld lost ground when Chinese companies scaled faster and drove down costs. Today, European firms struggle to compete. Europe has also experienced a loss of industrial scale. Although it pioneered offshore wind technology and continues to host leading turbine companies such as Siemens Gamesa and Vestas, their global market share has been steadily eroded by Chinese competitors like Goldwind and MingYang, which benefit from larger domestic markets and state-backed financing. The absence of equivalent industrial policies and coordinated scaling mechanisms in Europe has weakened its global competitiveness.

Europe also suffers from limited financial mobilization. The EU’s capital markets remain relatively fragmented, and Europe lacks equivalents to U.S. tech-driven venture capital ecosystems or China’s state-directed development banks. As a result, promising clean-tech startups often lack the financing to scale, or they relocate to markets where capital is more readily available. Finally, policy volatility and energy security trade-offs have further slowed progress. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine forced Europe to prioritize short-term energy security, including a temporary return to coal and expanded LNG imports. While renewables remain central to Europe’s long-term goals, this crisis response has diverted political focus and financial resources away from innovation.

In short, Europe excels in setting climate goals and deploying mature technologies, but it struggles with the scale, speed, and financing needed to dominate the next wave of innovation. China’s cohesive industrial strategy and America’s private-sector R&D dynamism have allowed both to outpace Europe in the past with solar, storage, and advanced grid technologies.

This belief that government involvement is counterproductive is underscored by the Trump Administration, which is systematically rolling back federal support for clean energy research and development, effectively cutting off a principal source of R&D capital. Programs within the Department of Energy that had funded renewable technology research, demonstration, and engineering are either reduced or deprioritized, while subsidies and regulatory support for fossil fuels are extended. Senior officials repeatedly argue that government “picking winners and losers” distorts innovation and that the private sector alone should determine which technologies succeeded.

In practice, this approach has meant reduced federal investment in next-generation renewables, energy storage, and grid modernization, precisely the areas where private markets have long struggled to invest at scale because of high upfront costs and long development horizons. The consequence is a federal policy environment that effectively reinforces the dominance of fossil fuels, while leaving the direction of America’s clean energy future to a bitter political contest: on one side, climate deniers and entrenched fossil fuel interests, and on the other, blue-state governments, environmental advocates, and climate scientists. Instead of providing coherent national leadership, U.S. energy policy has fractured along partisan lines, making long-term innovation and deployment hostage to the swings of electoral politics.

But Trump’s viewpoint that government involvement is counterproductive (at least in regards to energy renewables) is dangerously misleading. Over the past decade, China has emerged not only as the world’s largest producer of renewable technologies but also as one of its most important innovators, blending state direction with industrial scale to set the pace of the global energy transition.

Patent data illustrates the scale of this shift. Between 2010 and 2020, China accounted for more than 55% of all renewable energy patents filed worldwide, with over 400,000 patents in solar, wind, and energy storage technologies, compared with roughly 100,000 in the United States and 75,000 across the European Union. In solar photovoltaics alone, Chinese companies and research institutes have filed more than 200,000 patents since 2013, consolidating their dominance in both manufacturing and intellectual property. By 2022, China’s patent filings in renewable energy were growing at nearly twice the rate of those in the U.S., reflecting sustained government support and industrial mobilization.

Beyond volume, Chinese institutions have been central to deep, fundamental breakthroughs. In solar, firms such as LONGi and JA Solar have set successive world records for silicon–perovskite tandem cell efficiency, pushing beyond 34%, a milestone once thought unattainable in commercial-scale modules. In wind power, MingYang Smart Energy has developed the world’s first 18–20 MW offshore turbines, effectively doubling the size and capacity of earlier European designs. In energy storage, CATL has pioneered new chemistries, including sodium-ion batteries and ultra-long-life vanadium flow batteries, with commercial deployments already underway in grid-scale systems.

China has also invested heavily in fundamental research ecosystems, such as the National Energy Administration’s key laboratories and the network of New Research and Development Institutes (NRDIs) that bridge universities, SOEs, and private firms. These institutions have accelerated breakthroughs in ultra-high-voltage (UHV) transmission lines, AI-driven smart grid management, and large-scale hydrogen electrolysis, enabling technological advances that extend far beyond incremental improvements in efficiency.

In short, the last decade shows that China’s contribution to renewable innovation is not confined to scaling production. Through a combination of massive patent activity, pioneering fundamental research, and rapid commercialization, Beijing has ensured that its renewable energy leadership is grounded in both technology and manufacturing supremacy.

Setting Public Policy Through Private Capital Markets

Financing in the U.S. renewable energy sector is, above all, a private-sector affair. Project developers rarely rely on direct government funding; instead, they piece together capital from a combination of tax equity investors, commercial banks, and institutional investors such as pension funds and insurance companies. At the heart of this model lies the federal tax credit framework, which has given rise to a specialized field of finance known as tax equity. In this arrangement, large financial institutions provide upfront capital to renewable energy projects in exchange for the tax benefits those projects generate over time.

This structure has proven highly effective in mobilizing private investment, but it also concentrates immense influence in the hands of a relatively small number of major financial players, making project financing complex and, at times, inaccessible to smaller developers. Moreover, the system is heavily dependent on the stability of tax policy: when incentives are delayed, reduced, or allowed to expire, project pipelines stall.

China’s financing model stands in sharp contrast. Rather than setting public policy through private capital markets, Beijing deploys direct state-led financing. Institutions such as the China Development Bank and other state-owned banks provide long-term, low-cost loans to state-owned enterprises and private developers alike, ensuring a steady stream of capital regardless of short-term market conditions, or private financing objectives.

The result is two starkly different systems. In the United States, renewable energy growth depends on mobilizing private capital through tax incentives, an approach that effectively leaves public policy at the mercy of a handful of large financial institutions, not elected officials. The tax equity market is deliberately complex, restricting participation to a small circle of major banks and investors, which in turn creates inequality of access for smaller developers. This complexity also makes the system politically fragile: each change in Washington risks altering the tax code, stalling projects, and shaking investor confidence.

China, by contrast, harnesses the direct power of the state to finance renewables at scale. Through state-owned banks and enterprises, Beijing delivers long-term, low-cost capital with speed and predictability. This ensures that ambitious targets are not only set but consistently exceeded, transforming renewables from an uncertain investment into a guaranteed pillar of national strategy.

Ultimately, these two models shape more than domestic energy policy: they define the global race for industrial leadership. By marrying financing with industrial policy, China is dominating the global clean energy economy, while the United States is ceding competitiveness as it continues to rely on a system constrained by complexity, inequality, and political volatility.

3. Comparative Production and Capacity Analysis

The Difference of Scale

The past decade has witnessed an extraordinary divergence between China and the United States in renewable energy deployment. Both nations have expanded capacity, but the scale and speed of China’s progress have been unprecedented, leaving the U.S. trailing by a wide margin. By 2024, China had established itself as the undisputed leader in global renewables, with a portfolio that dwarfs America’s in every major category.

In 2024, China’s total installed renewable energy capacity reached 1,878 GW, compared to just 359 GW in the United States. Put differently, China’s renewable system is now 5.2 times larger than that of the U.S., a staggering gap that underscores the fundamentally different trajectories of the two countries.

This disparity holds across all major technologies. In solar power, China installed 887 GW of capacity, while the U.S. reached 177.2 GW, a fivefold advantage for China. In wind power, China stood at 521 GW, compared with 152.9 GW in the U.S., giving Beijing a 3.4x edge. These numbers reflect not only greater investment but also China’s ability to deploy at scale year after year.

A Decade of Growth: 2014–2024

The U.S. has certainly grown its renewable sector over the past decade, but the pace has been steady rather than exponential. China, in contrast, has undergone a massive transformation, turning itself into the engine of global renewable production.

From 2014 to 2024, the U.S. increased its solar capacity from 15.7 GW to 177.2 GW, a remarkable 1,029% increase. Wind grew from 64.2 GW to 152.9 GW, representing a 138% increase, while total renewable capacity rose from 80 GW to 359 GW, a 349% increase. These gains highlight strong progress, but they remain limited when viewed against the scale of China’s expansion.

Under the second Trump Administration, however, this momentum will slow or even stall. Trump has already rolled back Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) incentives, the most significant federal investment in clean energy in U.S. history. His administration is expected to rescind tax credits for wind, solar, and electric vehicles, while restoring full support for fossil fuels through subsidies, deregulation, and expanded oil and gas leasing. Programs at the Department of Energy that fund clean energy R&D and grid modernization, revitalized under Biden, are being cut or deprioritized, halting investment in next-generation technologies such as advanced batteries, small modular reactors, and hydrogen. Trump officials have also signaled plans to end federal support for transmission line expansion, a critical bottleneck for scaling renewables, and to weaken the EPA’s clean energy standards, giving utilities little incentive to shift away from coal and natural gas.

In effect, the rapid growth of U.S. renewables from 2014 to 2024 could represent a high-water mark rather than a launching pad. Without sustained federal support, the pace of solar and wind deployment will slow, investment will shift back toward fossil fuels.

China’s growth trajectory has been nothing short of exponential. In terms of production, solar generation soared from 29,195 GWh in 2014 to 839,040 GWh in 2024, a 2,774% increase. Wind production grew from 156,078 GWh to 997,040 GWh, an increase of 539%. Total renewable generation more than doubled, rising from 1.25 million GWh in 2014 to 3.26 million GWh in 2024, a 161% increase. The scale of these gains demonstrates the effectiveness of China’s state-driven approach, which consistently translates ambitious targets into realized output.

In 2024 alone, China added 373 GW of renewable capacity, shattering global records. This included 277 GW of new solar capacity, representing 45.2% year-on-year growth, and 80 GW of new wind capacity, a growth rate of 18%. By comparison, the United States added a respectable but modest 58 GW in 2024, including 39.4 GW of solar and just 5.6 GW of wind. China’s additions were 6.4 times greater than those of the U.S. in a single year, underscoring its ability to deploy capacity at a scale unmatched anywhere else.

The magnitude of China’s deployment becomes even clearer when placed in context. China’s 277 GW of solar capacity added in 2024 alone is nearly equivalent to the entire U.S. renewable capacity of 359 GW across all technologies. In effect, China added in a single year what has taken the United States decades to build.

China’s dominance extends beyond raw numbers to global influence. Between 2019 and 2024, China accounted for 40% of global renewable capacity expansion, compared with just 8% for the United States. By 2024, renewables made up 44% of China’s total installed capacity, while in the U.S., the share stood at roughly 30%. These figures highlight China’s position as the central driver of the global energy transition, while the U.S., despite notable growth, remains a secondary player in terms of scale and influence.

4. The Tibetan Plateau Project - the largest energy undertakings in human history

The Tibetan Plateau renewable energy project stands as one of the clearest illustrations of the scale and ambition that define China’s state-led approach to the energy transition. Rising more than 4,000 meters above sea level, the Plateau is often referred to as the “roof of the world.” Its geography, while inhospitable, offers some of the planet’s most abundant solar irradiation and strong, steady wind currents. Beijing has identified this high-altitude region as a strategic frontier in its effort to transform China’s energy system: one that can generate not only vast amounts of clean electricity for domestic consumption, but also supply surplus power for export to neighboring countries through cross-border transmission links.

The project is being developed by a consortium of state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Plans call for the construction of thousands of square kilometers of solar arrays and wind farms, integrated into a network of ultra-high-voltage (UHV) transmission lines that will stretch thousands of kilometers to deliver power from Tibet’s remote highlands to the industrial and population centers of eastern China. When fully built out, the Tibetan Plateau project is projected to reach a capacity of hundreds of gigawatts, putting it on par with the total renewable energy capacity of entire continents and making it the largest energy undertakings in human history.

The ambition of this project is matched by the severity of the challenges it faces. Tibet’s environment is among the harshest on Earth: the thin atmosphere and intense UV radiation test the durability of solar panels, while high winds, snow, and freezing temperatures complicate turbine operation and long-term maintenance. The rugged terrain makes construction and transport of equipment logistically daunting, requiring extensive investment in new roads, support facilities, and workforce accommodations. Beyond generation, the sheer distance from Tibet to China’s coastal demand centers necessitates an unprecedented expansion of UHV transmission infrastructure, with lines traversing thousands of kilometers of mountains, deserts, and river systems.

Beyond its domestic role, the Tibetan Plateau project also carries profound geopolitical implications. Tibet’s position at the crossroads of South and Central Asia makes it a natural anchor for China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) energy ambitions. By exporting renewable electricity across borders to Nepal, Bhutan, Pakistan, and eventually into Central Asia, China plans to weave its neighbors into a regional grid that reinforces both their dependence on Chinese energy infrastructure and Beijing’s influence. Just as pipelines once defined spheres of energy dependence, high-voltage transmission lines carrying Tibetan wind and solar power could create a new web of regional geopolitical alignment centered on China.

In this sense, the Tibetan Plateau project exemplifies more than just China’s determination to decarbonize. It embodies Beijing’s vision of using renewable infrastructure as a tool of both domestic resilience and regional power projection, demonstrating its capacity to lead the next era of global energy geopolitics.

The Tibetan Plateau project highlights the key features of China's state-led approach: its ability to mobilize massive resources, its long-term strategic vision, and its focus on large-scale infrastructure projects. The project demonstrates China's willingness to invest in projects that may not be economically viable in the short term but serve broader strategic objectives of energy security and technological leadership.

5. Competitive Dynamics and Trade Tensions

The rivalry between China’s state-led model and America’s market-driven approach has become one of the defining features of the global energy transition. China’s massive state investment and unparalleled economies of scale have pushed renewable energy costs down worldwide, but they have also provoked accusations of unfair competition, market distortions, and overcapacity. Western policymakers argue that China’s state-backed financing and vertically integrated SOEs give its companies advantages that private-sector competitors cannot match. In response, the United States and other developed economies have resorted to trade measures, including tariffs on Chinese solar panels, wind turbines, and battery products, as well as targeted subsidies and industrial strategies designed to rebuild domestic manufacturing capacity. These clashes reflect a deeper unease over technological dependence, energy security, and the fragility of global supply chains in an era of geopolitical rivalry.

United States Contributions to Renewable Energy Development

Both the United States and China have made critical contributions to the advancement of renewable energy technologies, though their strengths lie in different areas of emphasis.

The United States has distinguished itself in energy storage innovation, grid management, and financial engineering. U.S. companies and research labs have pioneered advanced battery chemistries, long-duration storage concepts, and smart grid technologies that improve efficiency and reliability. Firms such as Form Energy are developing multi-day iron-air batteries, while ESS Inc. is commercializing long-duration iron-flow systems, and Tesla has scaled lithium-ion storage globally through its Megapack platform. On the grid side, companies like Fluence Energy provide advanced digital management systems for utility-scale storage, while utilities such as NextEra Energy have become global leaders in deploying integrated renewable-plus-storage projects.

On the financial side, America created the tax equity market, which has mobilized billions in renewable investment, and it remains a global hub for green bonds, with major institutions like Goldman Sachs and Bank of America playing central roles in structuring deals. Specialized green investment funds and vehicles, such as those managed by BlackRock and Brookfield Renewable Partners, have reinforced the U.S. position as a leader in innovative project finance and risk management structures.

American research institutions continue to push the frontier of advanced materials and next-generation renewable technologies. The National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) has made breakthroughs in high-efficiency solar cells, including perovskite-silicon tandem designs, while universities such as MIT and Stanford are leading in materials science and modular storage R&D. Companies like First Solar have pioneered thin-film cadmium telluride (CdTe) panels that remain competitive on global markets, while startups such as Heliogen are innovating in concentrated solar power and thermal storage.

Taken together, these examples highlight the United States’ role as a driver of technological innovation and financial creativity, with firms and institutions shaping global models for the next generation of renewable energy systems. Unfortunately, this progress is likely to stall under the Trump Administration’s efforts to end renewable energy programs for both government and the private sector. A clear illustration is found in New England’s offshore wind industry, where projects such as the Vineyard Wind development off the coast of Massachusetts, the first large-scale offshore wind farm in the United States, have faced direct political opposition. Trump has repeatedly criticized offshore wind, and his administration issued an Executive Order in January 2025 halting any new wind farm projects.

The stakes are significant: Vineyard Wind, for example, is expected to generate 800 megawatts of clean electricity, enough to power more than 400,000 homes in Massachusetts, while reducing carbon emissions by over 1.6 million tons per year, the equivalent of taking 325,000 cars off the road. By targeting projects of this scale and importance, Trump signals a broader intent to slow or block the expansion of renewables, undermining one of the most promising sectors of America’s clean energy transition.

China’s Contributions to Renewable Energy Development

The China model has distinguished itself through industrial-scale innovation, rapid commercialization, and integrated infrastructure development. Chinese companies have become global leaders in both renewable energy hardware and deployment at scale. In energy storage, firms such as CATL (Contemporary Amperex Technology Co. Limited) dominate the global lithium-ion battery market, while also pioneering new chemistries such as sodium-ion batteries. Flow battery leaders like Dalian Rongke Power have built the world’s largest vanadium redox flow projects, and State Grid Corporation of China is driving the integration of these storage technologies into national transmission systems.

In grid management and efficiency, China has invested heavily in ultra-high-voltage (UHV) transmission lines, with State Grid and China Southern Power Grid at the forefront of delivering renewable electricity across thousands of kilometers. These innovations have created the backbone for integrating massive volumes of solar and wind into the national system. Projects like the Tibetan Plateau renewable mega-hub demonstrate China’s capacity to coordinate generation, storage, and transmission at a continental scale.

On the financing side, China does not rely on tax equity but instead channels investment through state-owned banks such as the China Development Bank and through a growing green bond market regulated by the People’s Bank of China. SOEs like China Three Gorges Corporation and the Big Five power generation companies (Huaneng, Datang, Huadian, Guodian, and State Power Investment Corporation) combine development, financing, and deployment in vertically integrated models that few other countries can replicate.

In advanced materials and next-generation renewable technologies, Chinese companies are setting world records in solar innovation. LONGi and JA Solar have achieved record-breaking efficiencies in perovskite-silicon tandem cells, pushing past the 34% barrier in lab and industrial-scale demonstrations. Trina Solar has commercialized high-performance modules for diverse environments, while MingYang Smart Energy and Goldwind are producing some of the world’s largest offshore wind turbines, with capacities exceeding 20 MW. Meanwhile, Envision Energy is innovating in digitalized energy management platforms that integrate renewables, storage, and smart-grid solutions.

Together, these companies illustrate how China’s strength lies not only in manufacturing scale but also in its ability to industrialize and commercialize innovations rapidly, often leapfrogging competitors and reshaping global supply chains in the process.

Taken together, these contributions highlight complementary strengths. The United States has excelled at pioneering technologies and financial models, while China has proven unmatched in scaling and industrializing innovations into systems that reshape global markets. The global renewable transition has been accelerated by both approaches: one driven by creativity and market finance, the other by scale, state coordination, and rapid deployment.

Unfortunately, the U.S. is reversing course. Under Donald Trump, federal leadership on clean energy has taken a 180-degree turn. Trump has repeatedly disparaged renewables, dismissing offshore wind by claiming: “I know a lot about wind. If your state has no wind, there’s no electricity. What happens when the wind doesn’t blow? … We’re going to keep coal. We’re going to keep natural gas. We’re going to keep oil.” He leveled similar criticism at solar energy, declaring: “Solar is very, very expensive and it’s not working so well, and I know a lot about solar. … Solar has a lot of problems.” These statements, coupled with policy rollbacks, signal a dramatic retreat from the innovation agenda that once positioned the United States as a leader in the renewable energy transition.

Implications for Developing Countries

Following the Trump Administrations new energy directions, the United States has significantly scaled back its international financial support for development, particularly affecting clean energy and essential public health programs in the Global South. Under President Trump’s second term, over 90% of USAID’s foreign assistance contracts were eliminated, as part of a sweeping $60 billion cut to overall U.S. aid budgets. it signals a broader withdrawal from competing for global clean energy finance. In emerging economies, such reduced availability of U.S. development funding means a void increasingly filled by Chinese state-backed initiatives, particularly through the Belt and Road’s green energy finance.

These budget realignments underscore a broader trend in which the “America First” approach has transitioned from rhetoric into policy: pulling back from global climate leadership and humanitarian commitments, with direct and disruptive consequences for developing regions that once relied heavily on U.S. support. Under the Trump Administration, the U.S. withdrew from the Green Climate Fund, leaving billions in pledged support for renewable projects in Africa, Asia, and Latin America unfulfilled. Even under the Biden Administration, political resistance in Congress has constrained appropriations to international climate and renewable programs, stalling U.S. contributions compared to China’s Belt and Road renewable investments. This retrenchment means that developing countries often turn to Beijing for comprehensive financing packages, technology transfer, and infrastructure support that Washington no longer consistently provides.

Global South governments are no longer passive recipients of outside assistance; they are increasingly sophisticated in structuring renewable energy partnerships. Many are explicitly prioritizing self-sufficiency, indigenization, and affordability over one-dimensional technology transfer. The goal is to ensure that renewable energy does not replicate the extractive patterns of the past, in which developing countries were relegated to the role of raw material suppliers in a global system dominated by foreign powers. Instead, leaders from Africa, Latin America, South Asia, and Southeast Asia are pressing for agreements that build local capacity in manufacturing, processing, and skilled labor, thereby retaining more value within their economies.

This shift reflects a broader determination to avoid the “resource curse” dynamics of the fossil fuel era where abundant natural resources often trapped nations in dependency and underdevelopment. By demanding local content requirements, negotiating for technology transfer tied to training and education, and fostering regional manufacturing hubs, Global South countries are positioning themselves not just as markets for renewable technologies, but as co-creators of the new energy economy.

The Global South’s Leapfrog Opportunity

Unlike advanced economies encumbered by decades of entrenched fossil fuel infrastructure, the Global South stands at a rare and strategic crossroads. Many developing countries have yet to lock themselves into large-scale coal, oil, or natural gas systems, which gives them the potential to leapfrog directly into clean energy pathways. This structural advantage spares them from many of the costly transition challenges confronting the United States, Europe, and other industrialized nations including stranded assets, political resistance from fossil fuel incumbents, and the slow process of retrofitting aging grids. Instead, Global South countries can build renewable systems on a relatively blank slate, positioning themselves as both growth markets for clean energy deployment and as bargaining powers in negotiations with China and the United States.

The scale of this opportunity is underscored by global energy forecasts. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), energy demand in 2035 is projected to be 6% higher than previously forecast in 2023, with nearly 85% of incremental electricity demand originating outside advanced economies. This shift highlights the centrality of the Global South to the future of global energy markets. South-East Asia alone could attract more than $1.5 trillion in clean energy investments by 2030, driven by rapidly growing urban populations, industrial expansion, and government-led energy strategies. Meanwhile, Africa and Latin America are poised to capture similarly vast inflows of capital, supported by abundant solar, wind, and hydropower resources.

Regional experiences illustrate how this leapfrogging is already underway:

- Vietnam has emerged as one of the world’s most remarkable renewable energy success stories, particularly in solar power. Between 2018 and 2021, the country achieved one of the fastest buildouts in global history, moving from virtually negligible solar capacity to more than 16 GW of installed capacity by 2021. This rapid expansion was driven by supportive feed-in tariffs (FITs) that guaranteed developers favorable prices for solar electricity, combined with concessional financing and technology from both Chinese and Western suppliers.

On the equipment side, Chinese firms such as JA Solar, Trina Solar, and LONGi provided the bulk of the photovoltaic modules at competitive prices, while companies like Huawei supplied inverters and digitalized grid solutions. Western and regional financiers also played a crucial role. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) provided concessional loans and risk guarantees, while institutions such as the World Bank’s IFC and Norwegian fund Norfund invested in utility-scale solar farms. Private investors from Singapore and Europe joined consortia to accelerate project financing, helping to spread both financial risk and technical expertise.

Policy support was especially significant in driving Vietnam’s solar boom. The FIT program, launched in 2017 and adjusted in 2019, created a race among developers to connect projects to the grid before tariff deadlines expired. This incentive mechanism catalyzed a rooftop solar boom, particularly among commercial and industrial users, who saw an opportunity to reduce costs and hedge against rising electricity demand. At the utility-scale level, large projects in Ninh Thuan and Binh Thuan provinces demonstrated how concentrated deployment could deliver grid-connected solar capacity almost overnight.

The speed of Vietnam’s buildout also highlighted challenges. Grid congestion and curtailment became pressing issues, particularly in the south-central provinces where solar resources are strongest. In response, the government, with support from international partners, began investing in grid modernization projects and exploring battery storage integration to stabilize supply.

Despite these hurdles, Vietnam’s experience underscores how a combination of smart policy, low-cost Chinese technology, and diversified Western financing can catalyze transformative growth in renewables within just a few years. Today, Vietnam stands as Southeast Asia’s renewable energy leader, and its model is being closely studied by neighboring countries seeking to accelerate their own transitions.

- South Africa has pursued a different strategy building its renewable energy capacity through the Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Procurement Programme (REIPPPP). Since its launch in 2011, the program has attracted more than $20 billion in private investment, making South Africa the continent’s largest renewable energy market by investment volume.

Through REIPPPP, a wide mix of foreign and domestic players have participated. On the wind side, Siemens Gamesa (Spain/Germany), Nordex (Germany), and Goldwind (China) have all supplied turbines, while local firms such as Mainstream Renewable Power South Africa have taken lead roles in project development. In solar, Chinese panel makers like JA Solar and Trina Solar dominate equipment supply, while U.S. investors, including Google and General Electric (GE), have backed selected projects with both financing and technology.

The financing model emphasizes transparency and risk-sharing. The World Bank’s International Finance Corporation (IFC), alongside South African banks such as Absa and Standard Bank, has provided syndicated loans, while international pension funds and infrastructure investors have increasingly entered the space. This blend of global capital and competitive pricing has allowed South Africa to secure some of the lowest renewable tariffs on the continent, even amid recent political and grid challenges.

- Brazil showcases the potential of hybrid approaches to renewable energy development. Long known for its pioneering role in biofuels, particularly ethanol production from sugarcane, which today accounts for more than a quarter of the nation’s transportation fuel mix, Brazil has in the past decade expanded aggressively into solar and wind power.

On the solar side, Chinese manufacturers such as LONGi and BYD have supplied the bulk of photovoltaic panels for Brazil’s utility-scale projects, leveraging their global manufacturing dominance to drive down costs. BYD even established a solar panel factory in Campinas, São Paulo state, underscoring Brazil’s appeal as a hub for local production. Meanwhile, U.S. and European financiers have played a crucial role in structuring the capital for these projects. For example, Goldman Sachs and BlackRock have been active investors in Brazil’s renewable energy companies, while the European Investment Bank (EIB) has financed major wind and solar installations.

Brazil’s wind sector is a similar story of hybridization. Domestic developers such as Casa dos Ventos and Omega Energia have partnered with European turbine makers like Vestas and Siemens Gamesa, while Chinese firms like Xinjiang Goldwind have entered the market to supply cost-competitive technology. At the same time, U.S. companies such as AES Brasil have expanded their renewable portfolios in the country, bringing project management and grid integration expertise.

The government’s energy auctions, run by Brazil’s National Electric Energy Agency (ANEEL), have been central to this process. By offering long-term power purchase agreements through transparent bidding, Brazil has attracted a mix of Chinese technology providers, American and European investors, and domestic developers. The result is a diversified financing and technology base that balances low-cost equipment imports with advanced grid solutions and private investment from global capital markets.

Through this hybrid model, Brazil has emerged as Latin America’s renewable anchor, demonstrating how the Global South can use competition between China and the U.S./Europe to its advantage, securing both affordability and technological sophistication while fostering domestic industrial participation.

- Kenya has positioned itself as a leader in renewable energy in Africa, with over 80% of its electricity already coming from renewable sources, largely geothermal. The country’s flagship Olkaria geothermal complex—operated by the state-owned Kenya Electricity Generating Company (KenGen)—is one of the largest in the world, producing nearly 900 MW of power. To expand beyond geothermal, Kenya has also embraced partnerships that bring in both Chinese and Western expertise.

The Lake Turkana Wind Power Project, Africa’s largest wind farm at 310 MW, was developed with a consortium that included Vestas (Denmark) as the turbine supplier, Norfund (Norway) and Finnfund (Finland) as financiers, and equity support from private investors. On the solar side, Chinese companies have been particularly active: Huawei provided digital inverters and smart grid technologies for solar farms, while PowerChina has been involved in engineering and construction.

Financing has come through diverse channels. The African Development Bank and Standard Bank (South Africa) have partnered with European DFIs, while Chinese policy banks have extended concessional loans tied to EPC contracts. This combination has allowed Kenya to deploy renewables quickly while maintaining a focus on domestic capacity-building. In 2023, the government launched the Kenya Energy Sector Roadmap 2040, which includes local manufacturing targets for solar equipment to prevent overreliance on imports and ensure jobs are created within the country.

Taken together, these case studies reveal a common theme: the Global South is no longer a passive recipient of technology transfers, but an increasingly assertive actor shaping the contours of the renewable economy. By leveraging both China’s scale and financing developing countries are forging hybrid models tailored to their own priorities of self-sufficiency, affordability, and industrial development.

Strategic Outlook

The United States faces a mounting challenge in securing the resources it needs for the energy transition under its current posture of reduced aid and limited engagement with developing nations. As Global South countries increasingly demand value-added partnerships, insisting on local processing of lithium, nickel, cobalt, and rare earths, as well as job creation and technology transfer, the U.S. risks being sidelined if it continues to withdraw from financing and capacity-building efforts. China’s Belt and Road Initiative, backed by state banks and comprehensive investment packages, has positioned Beijing as the partner of choice for many resource-rich countries, offering not just extraction contracts but also industrial parks, training programs, and infrastructure.

By contrast, U.S. development finance has become fragmented and constrained, focusing on risk-mitigation for private investors rather than long-term industrial partnerships. This strategy leave American firms at a disadvantage when bidding for access to critical minerals, as governments in Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia increasingly view U.S. offers as too narrow compared to China’s all-encompassing model. Unless Washington recalibrates by re-engaging with blended finance, technology-sharing initiatives, and direct support for local industrialization, it risks losing ground in the competition for the raw materials essential to solar panels, wind turbines, EV batteries, and other clean technologies. Under the current Administration that is highly unlikely. In a world where resources are leveraged through reciprocal partnerships rather than one-sided extraction, America’s current withdrawal strategy will undermine both its resource security and its long-term global leadership.

6. President Xi's Launches the Centerpiece of a New Energy and Economic Order

On September 1, 2025, Chinese President Xi Jinping delivered a landmark speech at the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) “Plus” Meeting in Tianjin, unveiling ambitious new initiatives for regional energy cooperation. His proposals represent the most comprehensive Chinese effort yet to build an integrated, multinational renewable energy ecosystem across Eurasia. The announcement signaled a dramatic escalation of China’s attempt to shape a China-centered alternative to Western-led energy systems, one that could eventually encompass 27 SCO member and partner states, representing more than 40% of the global population.

Xi’s Tianjin Declaration rests on three pillars: the creation of cooperation platforms in energy, green industry, and the digital economy; a commitment to expand solar and wind capacity by 20 GW across SCO countries over the next five years; and the integration of advanced technologies, including artificial intelligence and the BeiDou satellite system, into regional energy infrastructure. Educational and vocational cooperation centers will complement these efforts by developing the human capital needed for long-term sustainability.

SCO as the Platform for China’s Energy Diplomacy

Founded in 2001, SCO began primarily as a regional security alliance focused on counterterrorism, border management, and stability in Central Asia. Initially centered on what became known as the “three evils” of terrorism, separatism, and extremism, the SCO provided a platform for joint military exercises and intelligence sharing among China, Russia, and Central Asian states.

Over time, however, the organization steadily broadened its agenda. By the late 2000s, discussions had expanded to include economic coordination, infrastructure development, and energy security, reflecting the recognition that long-term stability depended as much on prosperity as on military cooperation. China, in particular, pushed for this evolution, aligning the SCO’s mandate with its own growing interest in securing energy supplies and building regional connectivity. The inclusion of India and Pakistan as full members in 2017, and Iran in 2023, further expanded the SCO’s scope and influence, transforming it into a major multilateral forum that spans Eurasia.

Today, the SCO encompasses China, Russia, India, Pakistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Iran, with Afghanistan, Belarus, and Mongolia as observers and several dialogue partners across Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. Collectively, these states include some of the world’s largest energy producers and consumers, making the organization an ideal platform for Beijing’s vision of cross-border energy integration.

The timing of Xi’s Tianjin declaration was no less significant than its content. It came amid intensifying U.S.–China rivalry over clean energy supply chains, rising concerns about energy security following global geopolitical disruptions, and mounting international pressure to accelerate renewable deployment. By using the SCO stage, Xi sought to recast the organization from its original role as a security forum into the centerpiece of a new energy and economic order, positioning China as the architect of a cooperative model that will rival Western-led initiatives such as the G7’s Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment.

The Three-Platform Strategy

At the heart of the Tianjin Declaration are three platforms designed to promote comprehensive regional cooperation. The energy platform is the centerpiece, calling for cross-border grid integration, standardized technologies, and joint development of large-scale renewable projects that leverage each country’s comparative advantages. If successful, this could create the world’s largest integrated renewable energy market.

The green industry platform aims to localize renewable energy manufacturing within SCO countries. By transferring technology, building local supply chains, and creating jobs, China seeks to extend its dominance in renewable manufacturing while reducing dependence on Western technology. With China already producing over 60% of the world’s solar panels and three-quarters of its lithium-ion batteries, this approach would anchor Eurasian economies firmly within Chinese supply networks.

The digital economy platform proposes AI-driven grid optimization, BeiDou satellite integration, and data-sharing arrangements to create smart, interconnected energy systems. Beyond efficiency, these initiatives deepen technological dependencies on Chinese infrastructure, embedding Beijing’s digital ecosystem within the energy architecture of partner countries.

Scale and The 20 GW Commitment

Xi’s pledge to add 10 GW of solar and 10 GW of wind capacity across SCO countries by 2030 translates into an estimated $30–40 billion in new investment, much of it expected to flow through Chinese development banks and state-owned enterprises. While the scale appears modest when compared with China’s own domestic expansion, 277 GW of solar and 80 GW of wind added in 2024 alone, the implications for many SCO members are transformative.

For Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, the initiative could more than double their existing renewable capacity, accelerating diversification away from fossil fuels and enhancing energy security. For Pakistan, it offers a critical lifeline in addressing chronic energy shortages that have constrained industrial growth and social stability. Across Central Asia more broadly, the initiative could reposition landlocked states not as energy importers, but as potential exporters of renewable electricity to larger neighbors through cross-border transmission infrastructure.