In the first 100 days of Donald Trump’s second term, his administration unleashed an extraordinary and relentless assault on environmental protections, executing 145 deregulatory actions, more than one per day. This sweeping offensive, already surpassing the environmental rollbacks of his entire first presidency, has targeted the full spectrum of environmental safeguards: from clean air standards and endangered species protections to wetland preservation and climate change mitigation. In a single day in March 2025, the Environmental Protection Agency announced 31 separate deregulatory moves, with Administrator Lee Zeldin triumphantly declaring that they were “driving a dagger straight into the heart of the climate change religion.” This is not merely a policy shift, it is an ideological crusade against the very idea of environmental stewardship.

Yet where are the protesters?

While Trump’s immigration raids ignited mass protests across the country, and his authoritarian overreach spurred the “No Kings” demonstrations, mobilizing between four and six million people in what may be the largest single-day protest in American history, the environmental movement has remained conspicuously silent. This silence is not merely perplexing; it is deeply alarming. At a time when ecological destruction threatens the very foundations of modern society, the absence of a robust environmental response reveals a troubling failure of democratic resistance, precisely when such resistance is most urgently needed.

The contrast is stark and undeniable. The 2017 Women's March mobilized 3.3 to 5.6 million people in response to Trump's misogynistic rhetoric. Immigration protests have repeatedly filled streets across major cities, with demonstrators risking arrest to oppose family separations and deportation raids. Even Trump's military parade prompted coordinated nationwide protests under the "No Kings" banner. These movements achieved something the environmental community has failed to accomplish: they transformed policy outrage into mass mobilization.

Meanwhile, environmental protests during the Trump era have remained scattered, localized, and strikingly insufficient when measured against the magnitude of the crisis they seek to confront. Participation in Earth Day 2025 is estimated in the low hundreds of thousands, nowhere near the millions required to signal a groundswell of public will. This marks a sobering decline from the first Earth Day in 1970, when 20 million Americans, roughly one in ten, took to the streets, sparking the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency and a suite of landmark protections. Today, the same movement struggles to gather enough citizens to fill a city park.

Why does environmental destruction, arguably the most urgent and far-reaching threat to human survival, fail to inspire the scale of resistance that other Trump-era policies have provoked? The answer lies not in apathy, but in the fractured state of the environmental movement itself, the psychological difficulty of mobilizing around slow-moving and abstract dangers, and the quiet spread of climate fatalism, a corrosive belief that change is no longer possible, which has stilled the passions of an entire generation of would-be activists.

The Unprecedented Scale of Environmental Destruction

To understand the magnitude of this mobilization failure, we must first grasp the unprecedented scale of environmental destruction unleashed by the Trump administration. The New York Times, working with Harvard Law School and Columbia Law School, documented that Trump's first term saw 98 environmental rules officially reversed, revoked, or rolled back, with an additional 14 rollbacks left in progress. Environmental law experts described this as "a very aggressive attempt to rewrite our laws and reinterpret the meaning of environmental protections," creating "a truly unprecedented legacy."

But Trump's second term has accelerated this destruction to breathtaking levels. The administration launched 145 environmental rollback actions in just its first 100 days, more than the total completed in Trump's entire first presidency. This "blitzkrieg," as environmental journalists have termed it, has targeted virtually every major environmental protection Americans have built over the past half-century.

The scope is staggering. The administration has deleted Biden-era green policies, frozen climate spending, withdrawn from the Paris climate accords for the second time, and begun rewriting pollution standards for cars, trucks, and power plants. Sprawling tracts of land, including in the Arctic, have been opened for oil and gas drilling. Commercial fishing has been permitted in previously protected ocean sanctuaries. Half of America's vast national forests can now be cut down for timber. Laws protecting endangered species face drastic rollbacks, while protected national monuments are being shrunk to accommodate extractive industries.

Yet this carnage has failed to generate the mass resistance that would seem proportionate to its consequences. To understand why, we must examine the deeper structural and psychological factors that distinguish environmental threats from the issues that do successfully mobilize millions of Americans.

The Fragmentation Trap: How Environmental Organizations Lost Their Movement

The most fundamental barrier to environmental mass mobilization lies in what organizational analysts call the "fragmentation trap," the environmental movement's evolution from a unified force into hundreds of disconnected, issue-specific organizations that compete for resources rather than coordinate for impact.

As Gideon Rosenblatt insightfully noted in his influential essay Movement as Network, today's environmental organizations are "so disconnected that they are barely recognizable as a movement—particularly by those within the movement itself." This disunity is rooted, in part, in the vast spectrum of environmental concerns. But more critically, it stems from what Rosenblatt identifies as "a lack of diversity in organizational models," which fosters competition for limited resources and discourages the kind of strategic collaboration and value-generating networks that have become standard practice in more agile, innovation-driven sectors of the private economy.

The consequences of this fragmentation are profound. For the average citizen hoping to engage meaningfully with environmental causes, the movement presents what Rosenblatt calls "a dizzying array of issue-specific organizations"—each narrowly focused, often working in silos. While some individuals may feel passionate about specific causes such as wetlands protection, air quality, or endangered species, many more are disoriented by the absence of a unified, holistic approach that reflects their broader ecological concerns. Even those who do commit find themselves dispersed across a sprawling constellation of small, disconnected groups, each with limited membership, diminished political leverage, and a collective voice too faint to be heard where it matters most.

This fragmented organizational landscape perpetuates a self-defeating cycle that severely hampers the potential for mass protest. Unlike the immigration rights movement which can coalesce around clear, emotionally resonant demands like “Stop family separations” or “End deportation raids,” the environmental movement lacks a unified voice, coherent messaging, or coordinated strategy. For a concerned citizen outraged by Trump’s environmental rollbacks, the path to action is anything but straightforward. Should they align with the Sierra Club’s campaign against Arctic drilling? Support the Natural Resources Defense Council’s legal battles over air quality? Join the Environmental Defense Fund’s climate lobbying efforts? Or throw their weight behind a local watershed protection group? Each organization has its own membership, its own funding imperatives, its own tactical playbook, and its own metrics for success.

The result is what social movement scholars describe as “resource fragmentation” representing a disintegration of collective energy across so many parallel efforts that no single entity commands the scale, legitimacy, or infrastructure to galvanize a truly national mobilization. When Trump announced his sweeping 31-action environmental rollback package in March 2025, there was no central organization with the authority or bandwidth to convene a unified response. Instead, dozens of groups issued separate press releases, called for isolated actions, and vied for limited media attention, guaranteeing that the response, however earnest, would be diffuse, diluted, and far less than the sum of its parts.

This fragmentation stands in sharp relief against the cohesion of other successful Trump-era movements. The Women’s March triumphed by forging a unified organizational framework capable of bridging diverse issues and constituencies. The “No Kings” protests drew strength from their ability to unite a broad coalition under a single, resonant message opposing authoritarian overreach. The immigration rights movement continues to mobilize effectively because it rallies around immediate, visceral injustices, family separations, deportation raids, that cut across organizational lines and demand a collective response.

In contrast, the environmental movement remains mired in its specialized silos, unable to transcend its internal divisions. It has lost the capacity to organize at scale. Citizens who might otherwise be galvanized into action find themselves adrift, unsure which group to support, unclear on what specific actions to take, and disheartened by the movement’s failure to offer a unified, forceful reply to Trump’s environmental rollbacks. The result is paralysis at precisely the moment when cohesion is most needed.

The Psychology of Distant Threats: Why Environmental Crises Don't Feel Urgent

Beyond the structural fragmentation of the environmental movement lies a more insidious obstacle to mass mobilization: the psychological distance that separates people from the nature of environmental harm. Unlike immigration raids, which produce immediate, visible suffering, or executive orders that trigger swift legal and political fallout, environmental deregulation often unfolds through delayed, diffuse, and statistical mechanisms that render its impact less tangible and its urgency more difficult to grasp.

This distance takes many forms, each of which erodes the momentum needed for collective action. Temporal distance dulls the sense of immediacy; threats that unfold over years or decades struggle to compete with the drama of real-time crises. When the Trump administration announces rollbacks that experts say will lead to “thousands of additional deaths from poor air quality each year,” the danger is cast into an indefinite future, disconnected from the present moment. When scientists warn of rising emissions “over the next decade,” such projections, however dire, lack the visceral punch of families being torn apart at the border today. In a culture attuned to immediacy, the slow violence of environmental degradation too often fails to command moral urgency.

Spatial distance compounds this problem. Environmental harms often occur in places removed from major population centers where protests typically happen. Arctic drilling affects remote wilderness areas that most Americans will never visit. Coal plant emissions disproportionately harm rural communities that lack the political power and media attention of urban centers. Even when environmental harms occur in cities, they are often invisible. Air pollution that gradually increases asthma rates, water contamination that slowly accumulates in bodies, toxic exposures that manifest as cancer years or decades later.

Perhaps most critically, environmental threats are hindered by what psychologists refer to as “statistical distance”—the difficulty of emotionally engaging with harms conveyed through numbers rather than human stories. The assertion that Trump’s rollbacks will result in “thousands of additional deaths” may be factually sound, but it remains emotionally inert. It lacks the immediacy and moral gravity of watching children separated from their parents at airports, or witnessing peaceful protesters brutalized by police. Environmental advocates have long grappled with this dilemma.

This emotional disconnect is further compounded by the complexity of environmental systems themselves. Unlike the clear cause-and-effect of many political actions, the ecological consequences of deregulation are diffuse, delayed, and deeply intertwined. When the Trump administration dismantles methane emission standards for oil and gas operations, most citizens cannot easily trace the arc from regulatory rollback to increased pollution, to degraded air quality, to heightened personal health risks and global warming. When national forests are opened to commercial logging, the resulting cascade, from deforestation to biodiversity collapse to climate destabilization requires a level of scientific literacy that many simply do not possess. As a result, the human stakes of environmental destruction remain obscured, and the public, disoriented, struggles to respond with the urgency the crisis demands.

By contrast, the dangers posed by other Trump-era policies possess an immediacy and clarity that readily galvanize public outrage. When ICE agents storm immigrant neighborhoods, the threat is tangible and deeply personal for those affected. When Trump signs executive orders expanding presidential authority, the constitutional ramifications are apparent to anyone with a basic understanding of civics. When he stages military parades or deploys troops against peaceful demonstrators, the authoritarian symbolism is unmistakable and deeply unsettling.

Environmental threats, however grave in their ultimate impact, rarely evoke the same visceral urgency. Their mechanisms are complex, their effects often delayed, and their victims dispersed or anonymous. This is not a reflection of public apathy or ignorance. Polling consistently shows that a majority of Americans express deep concern over environmental degradation. Rather, it underscores a profound psychological challenge: the difficulty of mobilizing collective action around threats that bypass our evolutionary wiring for immediate, visible danger. In the absence of a clear antagonist or a direct, emotional trigger, even existential risks can fail to ignite the fire of protest.

The Fatalism Factor: How Despair Paralyzes Environmental Action

Perhaps the most insidious obstacle to environmental mobilization is the rising tide of climate fatalism—the deepening conviction that ecological collapse is inevitable and that neither individual nor collective action can meaningfully alter its course. This sense of resignation, spreading most acutely among young people who should be the movement’s beating heart, marks a stark departure from the hope-fueled activism that once defined environmental advocacy. Where earlier generations marched with the belief that change was possible, many today retreat under the weight of despair.

Research by Ipsos reveals that young people are 66% more likely to express fatalism about humanity’s ability to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to levels that could slow climate change. This mindset, what scholars term "ecological fatalism," is characterized by a bleak fusion of anxious anticipation and hopeless resignation: a vision of a world becoming uninhabitable, a future slipping beyond reach, and a pervasive belief that meaningful intervention is no longer possible. Though over 80% of young people report being worried about climate change, this concern increasingly coexists with anger, grief, and paralysis rather than hopeful engagement.

The consequences of this fatalism for protest participation are profound. As one researcher observed, "fatalistic beliefs directly reduce behavioral change and willingness to pay to address climate change." When individuals believe the outcome is preordained, when disaster is seen as certain, they are far less likely to take the risks or make the sacrifices required for collective resistance. Why show up to a march if you believe the battle is already lost? Why risk arrest for a cause you fear is destined to fail? In this way, fatalism becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy that silences action before it begins, and leaving the field empty when it most demands to be filled.

This climate fatalism stands in sharp contrast to the hope-driven narratives that have fueled history’s most successful social movements. The civil rights movement prevailed not merely through moral clarity, but by instilling a collective belief that justice was achievable through sustained action. The women’s suffrage movement galvanized millions by charting a clear path from protest to political empowerment. Even recent Trump-era mobilizations, such as the “No Kings” protests, have succeeded by framing resistance as both urgent and potentially transformative by affirming that participation matters, and that outcomes can be changed.

By comparison, the environmental movement has increasingly leaned into a lexicon of despair. Its dominant rhetoric, however scientifically grounded, often veers into apocalyptic messaging that emphasizes the enormity of the crisis while offering few credible routes to resolution. Terms like “climate emergency,” “ecological collapse,” and “mass extinction” have become rallying cries that, paradoxically, can silence rather than stir, engendering a passive surrender to what is perceived as an unavoidable catastrophe.

This sense of doom is further magnified by the digital architectures through which most young people now encounter environmental news. Researchers warn of "algorithmic manipulation" by social media platforms that disproportionately amplify negative headlines from images of burning forests, collapsing ice shelves, to dying wildlife, while filtering out stories of progress, resilience, or innovation. The result is a steady drip of despair that fosters “apocalypse fatigue,” a psychological numbing that blunts emotional response and erodes the will to act. For a generation already burdened by ecological anxiety, this curated onslaught of hopelessness can be paralyzing, muting the very energies most needed to confront the crisis.

Environmental activists today increasingly speak from a framework shaped not by the prospect of triumph, but by the inevitability of loss. Our language revolves around “managed decline,” “adaptation to unavoidable change,” and “harm reduction, ” terms that reflect a sober scientific understanding of the crisis, but offer little of the transformative vision that animates successful social movements. While this realism may be intellectually honest, it inadvertently cultivates a psychological atmosphere that stifles the very energy required for mass mobilization.

The result is a movement immobilized by the weight of its own insight. The deeper we delve into the scale and complexity of ecological collapse, the harder it becomes to inspire the kind of hope-based collective action needed to confront it. This dynamic gives rise to what social movement theorists have termed the “mobilization paradox”: those most informed about the depth of the crisis are often the least capable of rallying broad resistance. In place of rallying cries, we offer forecasts; in place of possibility, prognosis. And so, the environmental movement finds itself caught in a tragic bind, possessing unprecedented awareness, yet unable to convert that knowledge into the momentum for meaningful change.

The Burnout Crisis: How Movement Culture Drives Away Activists

The environmental movement’s struggles with mobilization are not only structural and psychological, they are also deeply cultural. Unlike other social movements that have cultivated supportive ecosystems to sustain long-term engagement, the environmental movement has, in many cases, developed internal dynamics that alienate the very people it most urgently needs. Participants increasingly describe activist spaces marked by burnout, tokenism, and the marginalization of frontline communities, conditions that sap energy, fracture solidarity, and erode the movement’s moral authority.

Research has found that despair over climate change leads to feelings of exhaustion and that exhaustion seems almost inevitable for climate activists. Unlike other social movements that can point to concrete victories and progress, environmental activists face what seems like an endless series of defeats punctuated by occasional, insufficient policy wins.

This creates what psychologists call "learned helplessness," the belief that one's actions cannot meaningfully influence outcomes. When environmental activists spend years fighting individual rollbacks, only to see dozens more implemented while they were focused elsewhere, they begin to internalize the futility of their efforts. The result is a movement culture characterized by what one observer called "apocalypse fatigue" and "climate grief" rather than the energizing hope that sustains other forms of activism.

The contrast with successful social movements is again instructive. The civil rights movement, despite facing enormous obstacles and setbacks, developed cultural practices that sustained activists through long struggles. The labor movement created solidarity networks that supported workers through difficult organizing campaigns. Even recent movements like Black Lives Matter have developed mutual aid networks and trauma-informed organizing practices that help activists manage the psychological toll of their work.

The environmental movement has, for the most part, failed to cultivate the supportive cultural practices that sustain long-term activist engagement. Unlike grassroots social movements rooted in mutual care and collective resilience, many environmental organizations operate more like professional advocacy firms, staffed by employees whose relationship to the cause is mediated through employment rather than through shared struggle and community.

The Specialization Trap: How Expertise Undermines Mass Appeal

The environmental movement confronts a singular challenge that sets it apart from other social movements: the formidable technical complexity of the issues at its core. While immigration rights advocates can galvanize support around clear moral imperatives like “keep families together,” and pro-democracy movements rally behind accessible principles such as “no one is above the law,” environmental activists must contend with layers of scientific uncertainty, intricate regulatory frameworks, and deeply interwoven ecological systems that resist simplification.

This complexity gives rise to the “specialization trap”—a dynamic in which organizations become increasingly focused on narrowly defined, technically dense issues that demand specialized expertise. Over time, environmental groups develop deep knowledge in specific policy arenas: air quality standards, climate mitigation strategies, endangered species protections, toxic chemical regulations. While this specialization is essential for effective policy work, it erects barriers to broad public engagement. The more expert the movement becomes, the more inaccessible it often becomes to the very public it seeks to mobilize. In contrast to movements that thrive on moral clarity and universal language, the environmental movement often speaks in the lexicon of legal statutes, carbon metrics, and risk assessments leaving potential allies confused, alienated, or unsure of where they fit.

The result is environmental messaging that speaks to policy experts rather than ordinary citizens. When Trump's EPA announces plans to eliminate methane emissions standards for oil and gas facilities, environmental organizations respond with detailed analyses of regulatory frameworks, scientific studies of methane's climate impacts, and technical critiques of the administration's cost-benefit analyses. While this expertise is valuable for legal challenges and policy advocacy, it does not translate into the kind of emotionally resonant messaging that mobilizes mass protests.

Contrast this with how other movements frame their issues. When Trump announces immigration raids, advocates don't respond with technical analyses of immigration law. They tell stories of families being separated and communities being terrorized. When Trump expands executive power, pro-democracy advocates don't focus on constitutional law details, they warn about authoritarianism and the threat to democratic governance. These movements generate involvement because they translate complex policy issues into simple moral frameworks that ordinary people can understand and act upon.

Environmental advocates, however, often seem trapped by their own expertise. They know that environmental issues are complex, interconnected, and scientifically nuanced, and they feel obligated to communicate this complexity rather than simplifying it for mass consumption. The result is messaging that educates rather than mobilizes, that informs rather than inspires, that speaks to the head rather than the heart.

The specialization trap is further deepened by the environmental movement’s fraught relationship with scientific uncertainty. Environmental advocates, grounded in a culture of intellectual rigor, often feel compelled to acknowledge the limitations and nuances of scientific knowledge, even when such caution dilutes the urgency of their message. Climate scientists speak in terms of “confidence intervals” and “probability ranges,” while environmental health researchers refer to “elevated risks” and “statistical associations” rather than asserting direct causality.

Though this restraint reflects scientific integrity, it produces rhetoric that is ill-suited to mass mobilization. When environmental advocates warn that Trump’s regulatory rollbacks “may increase the risk of adverse health outcomes” or “could contribute to climate change impacts,” they are offering statements that are empirically sound but emotionally inert. The language of uncertainty which is necessary in peer-reviewed journals becomes a liability in the public square, where clarity and conviction are the lifeblood of collective action.

Other movements are not constrained by the same epistemological caution. Immigration advocates can declare with moral certainty that deportation raids tear families apart. Defenders of democracy can state, without equivocation, that authoritarian overreach threatens constitutional rule. The environmental movement, by contrast, in its steadfast commitment to scientific accuracy, often forfeits the moral clarity and rhetorical power that mobilize the public. Its truth is careful, conditional, and probabilistic, precisely at the moment when people yearn for conviction and a call to action.

This dilemma is further compounded by the internal divisions created by the specialization trap. Environmental organizations often operate in distinct silos: wilderness preservationists prioritize different goals than urban air quality advocates; climate campaigners focus on systemic carbon reductions, while toxics groups zero in on chemical exposure; wildlife defenders speak a different language than those advancing renewable energy policy. These divergent priorities, while reflective of the ecological system’s inherent complexity, pose a formidable challenge to movement cohesion.

The result is a movement fractured in voice, vision, and strategy. Rather than projecting a unified front, it speaks through a cacophony of frameworks and agendas that is confusing rather than compelling to potential allies. Citizens inclined to join the cause find themselves unsure of what exactly is being asked of them, what outcomes are being pursued, and how their participation fits into a broader struggle. In a time that demands clarity and coordinated resistance, the environmental movement too often presents itself as a constellation of causes, rather than a singular, mobilizing force.

The Institutional Capture Problem: How Professionalization Killed the Movement

The environmental movement’s mobilization crisis is also deeply entangled with a phenomenon described as “institutional capture, ”the gradual transformation of grassroots activism into a network of professionalized advocacy organizations that prize insider influence over mass engagement. While this evolution has endowed the movement with valuable policy expertise and legal capacity, it has also profoundly reshaped its relationship to its grassroots base, diminishing its ability to inspire and sustain large-scale public action.

Today’s environmental landscape is increasingly dominated by “advocacy organizations” rather than true “membership organizations.” These institutions are staffed by professional advocates who engage with environmental issues as a career, and they are sustained primarily by foundation grants and major donor funding rather than by broad-based membership dues. This model brings institutional stability and technical proficiency, but it comes at a profound cost. These organizations are more attuned to the policy preferences of elite stakeholders than to the mobilization needs of everyday citizens. In prioritizing access to power over the power of the people, the movement has inadvertently traded the disruptive energy of the street for the cautious diplomacy of the boardroom and in doing so, has lost the vital spirit of its founding.

This institutional architecture carries profound consequences for public mobilization. Professional advocacy organizations prioritize insider strategies, lobbying legislators, filing lawsuits, and navigating regulatory corridors, approaches that demand technical expertise and elite access rather than popular engagement. Success is typically measured not by the breadth or depth of public mobilization, but by policy wins, legal rulings, and mentions in influential media. When such organizations do organize protests, these actions are often orchestrated as performative spectacles aimed at generating press coverage, rather than as authentic manifestations of grassroots power.

The contrast with other successful social movements is striking. The civil rights movement was anchored in membership-based organizations such as the NAACP and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which were directly accountable to their communities and drew strength from their capacity to mobilize collective action over time. The labor movement remains rooted in unions, institutions that represent their members’ concrete interests and can summon mass participation through strikes and coordinated campaigns. Even contemporary movements like Black Lives Matter emerged not from policy think tanks or nonprofit bureaucracies, but from the raw energy of grassroots organizing and lived experience.

The environmental movement, unlike many of its counterparts, has largely forsaken its membership-based roots in favor of professionally managed campaigns that replicate the appearance of grassroots activism without cultivating its substance. These organizations excel at amassing email lists, launching digital petitions, and curating media narratives, but they falter when it comes to sustaining the kind of high-risk, high-commitment collective action that drives real change. Bereft of authentic, community-anchored power, the movement’s ability to disrupt, demand, and ultimately transform is irrevocably damaged.

This shift toward professionalization has also given rise to institutions prioritizing their own survival over their founding mission. Environmental organizations, increasingly reliant on foundation grants, donor relations, and access to policymakers, begin to orient themselves around preserving funding pipelines, cultivating political respectability, and safeguarding institutional reputations. As a result, they become more risk-averse, more inclined toward incrementalism, and less willing to embrace the bold, unflinching rhetoric that mass mobilization demands. The fierce urgency of the ecological crisis is too often softened into polite advocacy, muted by the very structures that claim to speak for the planet.

The result is a landscape of environmental organizations more inclined to operate within the boundaries of existing political and economic systems than to challenge their foundations. They champion market-based solutions that pose no real threat to corporate power, endorse incremental policy reforms that leave deeper structural injustices intact, and shy away from the kind of bold, confrontational tactics that might unsettle elite allies. While this approach may yield modest policy gains, it lacks the moral clarity and visionary ambition that once was the lifeblood of the environmental movement.

At the core of the environmental movement’s strategic timidity lies a deeper structural constraint: its growing dependence on foundation funding. While philanthropic support has provided vital resources, it has also quietly, yet profoundly, reshaped the movement’s priorities. Foundations tend to favor narrowly scoped projects with measurable deliverables, directing funding away from the expansive, relational work of grassroots organizing. They privilege policy sophistication and insider access over deep community roots or disruptive capacity. The bureaucratic burdens of governmental and foundation support, rigorous reporting requirements, metric-driven evaluations, and alignment with donor-defined goals, consume organizational energy and subtly redirect program design toward institutional expectations rather than needed solutions.

In effect, the very funding structures intended to support the movement have, in many cases, pacified it. It has diverted our radical edge into technocratic channels that secure grants but fail to galvanize public participation. What was once a force for civil disobedience, public awakening, and structural challenge now too often functions as a polite policy intermediary.

The result is a movement increasingly accountable to its benefactors. While these organizations often speak in the name of the public interest, they lack the democratic legitimacy that arises from genuine grassroots accountability. When they issue calls for protest or public action, they do so without the deep, organic community networks that sustain other social movements, and too often, those calls are falling flat.

The problem of institutional capture is further deepened by a more corrosive dynamic: corporate capture. Major environmental organizations have accepted funding from fossil fuel giants, entered into partnerships that function more as public relations cover than genuine reform, and lent their credibility to market-based “solutions” that safeguard corporate profits rather than ecological integrity. In the pursuit of access and financial stability, the movement has often sacrificed its moral compass, trading the uncompromising clarity of its founding vision for a seat at tables it once sought to overturn.

While such partnerships may yield short-term gains—grants, visibility, or a voice in policy discussions—they come at a steep cost. They blunt the movement’s capacity to speak truth to power, to name corporate extraction as the engine of planetary collapse, and to demand the systemic transformation that genuine environmental justice requires. Organizations tethered to corporate funding cannot credibly challenge the status quo from which their benefactors profit. Instead, they become enmeshed in preserving the very systems they should be confronting, advancing solutions that appease boardrooms rather than match the urgency and scale of the crisis at hand.

In aligning too closely with the establishment, the environmental movement has become complicit in its own irrelevance, offering reforms where revolution is needed, and consensus where confrontation is demanded.

The Path Forward: Rebuilding Environmental Resistance

The environmental movement’s mobilization crisis is not a foregone conclusion. The same movement that once brought 20 million Americans into the streets for Earth Day 1970, helping to usher in the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, and the Environmental Protection Agency, still holds the latent power to galvanize mass resistance to the environmental rollbacks of the Trump era. But unlocking that potential will require a profound reimagining of how the movement operates, how it connects with its constituencies, and how it frames its message to the broader public.

First and foremost, the movement must confront and transcend its chronic organizational fragmentation. While the diversity of environmental issues necessitates a variety of specialized organizations, that specialization must be counterbalanced by unified structures capable of coordinating large-scale, collective action. What’s needed is not consolidation, but a strategic federation umbrella that can align messaging, synchronize tactics, and speak with one voice when the moment demands it.

Environmental organizations would do well to study the successes of coalitions like the Women’s March and the “No Kings” protests, both of which managed to unite disparate groups under a common banner with clear demands and resonant moral clarity. These movements proved that broad-based alliances, when rooted in shared purpose and cohesive strategy, can overcome ideological and organizational divides to create moments of national reckoning. The environmental movement must now do the same if it is to rise to the urgency of the times and reclaim its lost power to shape the future.

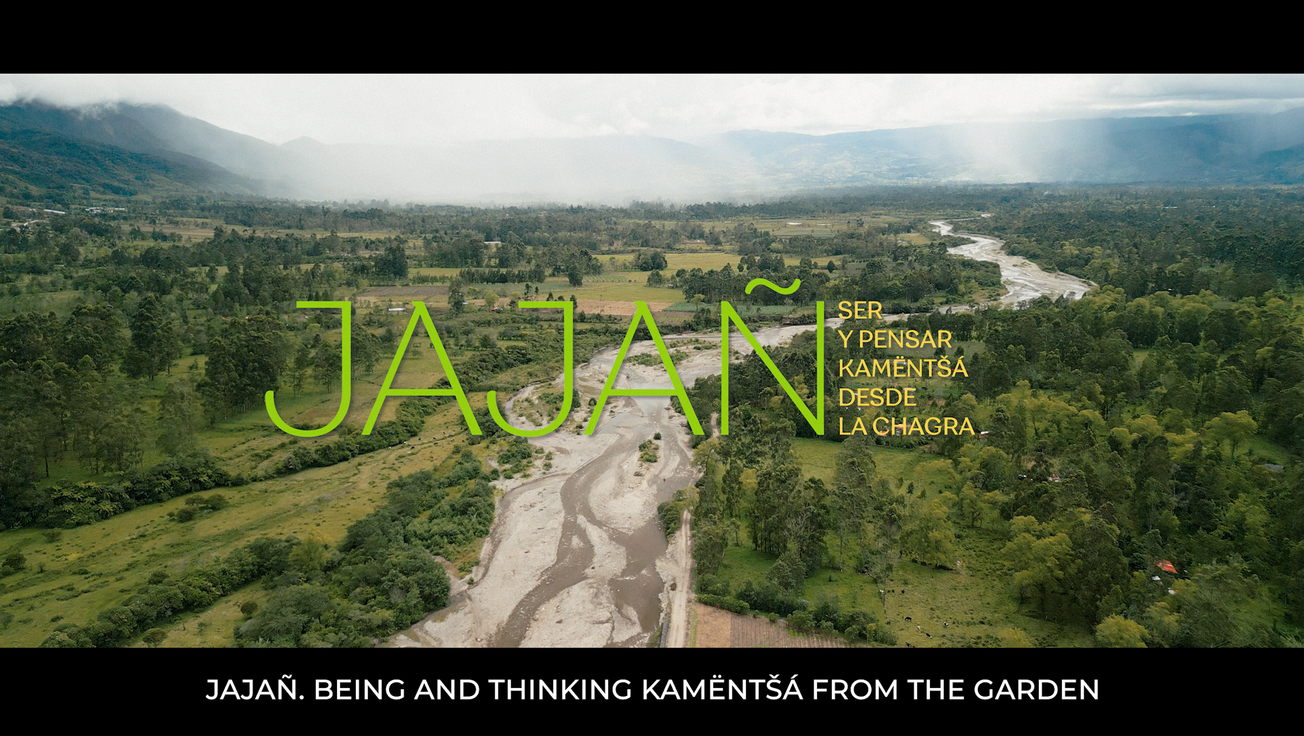

This coordination must reach beyond the traditional confines of the environmental movement to embrace a broader and more inclusive coalition, one that brings in environmental justice communities, labor unions, faith-based groups, and other constituencies that are directly impacted by ecological degradation but have too often been marginalized in mainstream environmental organizing. The movement cannot hope to achieve mass mobilization by speaking only to itself. It must forge authentic alliances that reflect the full spectrum of public interest in environmental protection and climate justice.

Second, the environmental movement must transform how it communicates. Environmental advocates must stop speaking primarily as policy experts and begin speaking as moral leaders. They must recast environmental destruction not as a technical challenge to be solved by specialists, but as a profound ethical crisis that demands action from everyone. Only by grounding the environmental struggle in lived experience and moral clarity can the movement hope to reclaim the emotional power necessary for mass mobilization.

Third, the environmental movement must reclaim the language of hope. To inspire sustained mass mobilization, it must cultivate narratives that affirm the power of collective action and convince people that their efforts can still shape meaningful change. This means lifting up stories of environmental victories, celebrating successful acts of resistance, and drawing clear lines between protest and policy impact. Amid the gravity of the ecological crisis, the movement must learn to communicate not just what is at stake, but what remains possible.

This is not a call for naïve optimism or a denial of hard truths. It is a call for strategic storytelling—narratives that confront the scale of the crisis while reinforcing the agency of those who dare to confront it. Environmental advocates must learn to speak in a register that acknowledges danger without surrendering to despair, one that insists that while the challenges before us are immense, they are not immutable. The path forward may be narrow, but it exists and it can be widened by collective effort, courage, and sustained public will.

In short, the movement must help people believe again: that the future is not yet written, that their voices matter, and that the arc of ecological history can still be bent toward justice. Without this belief, no protest can endure; with it, even the most entrenched systems can be transformed.

Fourth, the environmental movement must reckon with its internal culture and commit to building inclusive spaces that sustain activists rather than exhaust them. This requires a deliberate and ongoing effort to center the leadership, wisdom, and lived experience of frontline communities; and to cultivate mutual aid networks that support activists as they confront the psychological and emotional burdens of environmental struggle. The environmental movement must move beyond the transactional culture of professional advocacy and toward a relational ethic rooted in solidarity, shared struggle, and collective care.

What is needed is a movement culture that feels like community, not a career ladder. Only in such spaces can the movement retain its most passionate organizers, develop deep trust across lines of difference, and build the resilient social fabric required for transformative change.

Finally, the environmental movement must return to membership-based organizing that creates genuine grassroots accountability rather than dependence on governmental, foundational and corporate funders. This means building organizations that are accountable to their members rather than their donors, that measure success by their capacity to mobilize collective action rather than their policy expertise, that prioritize grassroots power-building rather than insider access.

This is not a call to abandon policy advocacy or legal strategy, but to root those insider tactics in the strength and legitimacy of genuine grassroots power. Environmental organizations must return to its roots of movement-building: cultivating broad membership bases that can sustain long-term organizing, provide democratic input into strategic priorities, and mobilize for sustained, collective action when the moment demands it.

The environmental movement holds the potential to become one of the most powerful engines of social transformation in human history. The ecological crisis will reach into every corner of our lives, cutting across race, class, and political affiliation ultimately exposing the shared vulnerability at the heart of the human condition. Defending the natural world is not a niche cause or a partisan issue; it is a moral imperative bound to our most cherished values: the health of our bodies, the strength of our communities, the future of our children, and the pursuit of justice across generations. The solutions to global warming ecological collapse promise more than mere survival, they offer a blueprint for a more equitable, resilient, and life-affirming world in which all can flourish.

To fulfill its extraordinary promise, the environmental movement must undergo a profound reawakening—a radical reorientation that reclaims its anti-establishment roots and confronts the unsettling truth captured in Pogo’s enduring warning from the 1970s: “We have met the enemy, and he is us.” The enemy is not external; it is embedded in the way we have chosen to live, in the systems we sustain, the comforts we normalize, and the disconnection from natural constraints we accept as inevitable.

The movement must transcend its internal fractures and forge coordinated, unified structures capable of galvanizing mass mobilization. It must once again become a moral force that speaks not only to the intellect, but to the soul, crafting narratives that stir conviction rather than resignation, that awaken a deep sense of purpose rather than despair. Our messaging must elevate courage above fear, and offer not just a diagnosis of collapse, but a vision of possibility. The future is not yet written; it remains a terrain of struggle and imagination, a landscape still waiting to be reshaped by the will of the people.

The road ahead is uncertain. But the horizon remains open, and the possibilities are profound. Whether the environmental movement rises to meet this moment will determine not only the fate of the natural systems upon which our life depends, but also the future of democratic resistance, and with it, the very notion of collective agency in a Democratic society.

The stakes could not be higher. Trump’s campaign of environmental dismantlement threatens far more than forests, rivers, and clean air; it strikes at the heart of democratic governance itself. When science is silenced, regulation gutted, and public lands auctioned off to private interests, it is not only the environment that suffers, it is the democratic infrastructure that enables us to defend it. If the environmental movement fails to summon a mass, unified resistance to this assault, it will not only fall short in its mission to protect the planet, but in its deeper responsibility to uphold the democratic ideals that make such protection possible.

The choice before us is stark. The environmental movement can continue along its current course, fragmented, professionalized, and increasingly marginalized or it can reclaim its soul, rebuild its grassroots foundations, and rise again as a force capable of mass mobilization and transformative change. Upon this decision rests not only the future of environmental protection, but perhaps the fate of the democratic institutions that make such protection possible.

The movement stands at a crossroads. One path leads deeper into fragmentation, disillusionment, and eventual irrelevance. The other points toward unity, moral clarity, and the rekindling of collective hope, a path that harnesses the full power of the people to confront an existential crisis with courage and purpose. The future hangs in the balance.

The time for choosing is now.